Ripples spread from discovery of gravitational waves

- Published

This aerial view of the LIGO experiment in Louisiana shows both of the laser beam pipes heading off from the main building

Three months ago scientists announced they had discovered evidence for the existence of gravitational waves. Ripples in the very fabric of our reality that nicely proved something Einstein suggested a century ago and also gave us an entirely new way to study the universe.

These big physics discoveries always involve huge teams of researchers from right across the planet, but the University of Birmingham, external has a key role, both in building the detector itself and in analysing the data it produces.

So now the scientific dust has settled I spent some time with the researchers at the university to get the behind-the-scenes story of the discovery and to ask them what they plan to do next.

The LIGO experiment

The Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, external or (LIGO for short) is based in America. It's actually two massive experiments, one in Hanford, Washington and another in Livingston in Louisiana. You need a lot of space for this experiment as you'll be bouncing lasers up and down pipes four kilometres long. And you also need to put the experiment as far away from noise and general vibration as possible. Gravitational waves are so small and so hard to detect that the vibration of waves on a distant shore is enough to mess up the measurements. So LIGO was built in pretty remote areas.

LIGO works using a very special laser beam which you split it in two and send each bit down two four-kilometre pipes which are at right angles to each other. At the end of each pipe is a mirror which bounces the laser straight back down the pipe. The two beams are then recombined and should in theory cancel each other out.

But if any gravitational waves have passed through the experiment, the distance the beams travel in their pipes will no longer be the same. Reality has been wobbled by the gravitational wave itself. And so when you recombine the laser beams this difference shows up as a pattern.

The world's best ruler

But the waves are so small, so quiet relative to all the other potential sources of noise, that we've spent half a century getting to the point where we can even build this experiment. LIGO needs to detect a change that's equal to a millionth of a millionth of a millionth of a meter, or one one-thousandth the diameter of a proton.

LIGO scientists say it is the most precise measuring device ever built.

So you can imagine how vital it is to make sure LIGO doesn't pick up any other disturbance. From people walking nearby to the Brownian motion of the surface of the mirrors themselves.

Along with other UK universities, it was Birmingham that helped create a system to hold the mirrors at the end of the tunnels so they could reflect the laser beams without adding any noise to the system. It's an extraordinary achievement involving wires made of glass and an amazing pendulum arrangement.

LIGO wasn't officially switched on yet

This is one of the four-kilometre pipes in Louisiana that LIGO bounces a laser beam down

But all this is really new. In fact they hadn't officially turned LIGO on, they were just conducting an engineering check, when they detected what appeared to be a perfect gravity wave. So perfect in fact all the scientists (including those heavily involved in the analysis in Birmingham) suspected it wasn't a real signal but a fake. Often those in charge will introduce fake signals to an experiment like this to make sure the experiment and the scientists are all working perfectly.

Can you imagine the emails and phone calls as it became apparent what was really going on? That this was the real thing! A real gravitational wave signal produced by the universe and not a test at all.

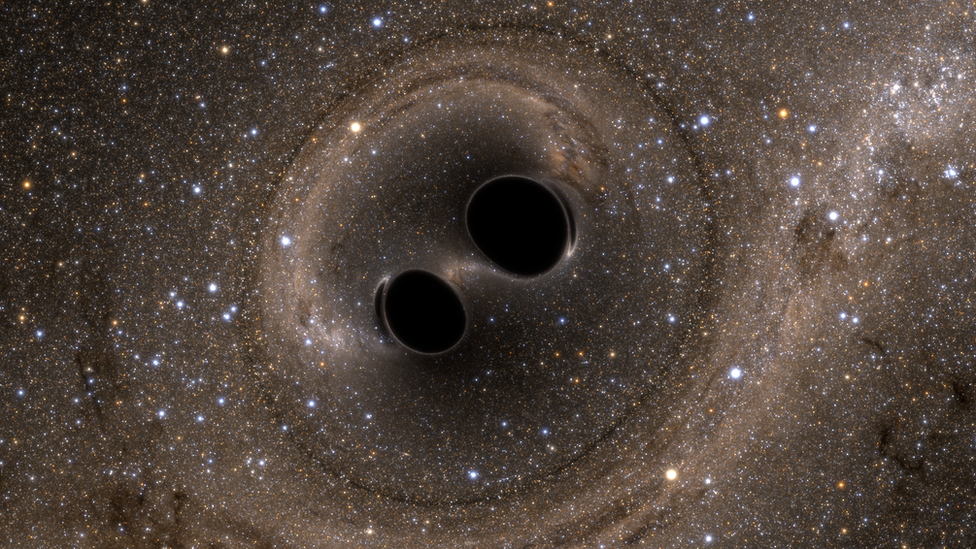

The gravitational wave signal itself came from an event we had never even seen before. It was created by two black holes, locked in a death spiral, that collapsed into each other and in split second generated more energy than all the stars in all the galaxies in the universe.

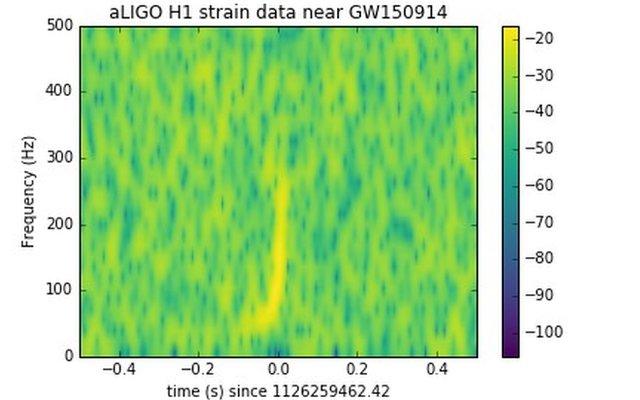

But the gravitational wave we detected from all that lasted less than half a second. Just as predicted, LIGO saw a brief little "chirp". Search on social media for "Chirp for LIGO", external and you can find plenty of scientists making this happy this little noise as a celebration of the discovery.

"Chirp" for LIGO

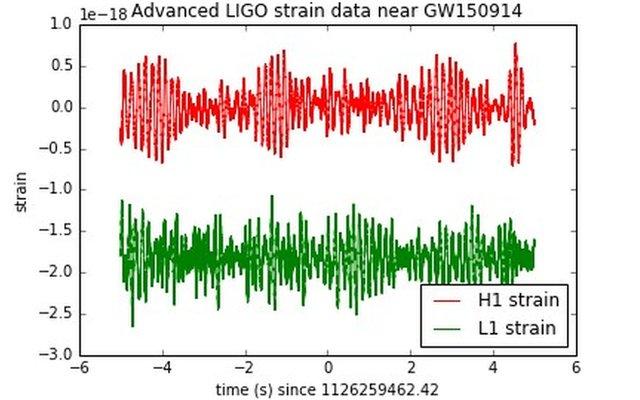

The graphs show real data from the experiment. At the top you can see just how noisy this data is, you really can't see any signal. But then automated systems kick in to say there is something there and the humans take over. Zooming in to that split second where the signal, the "chirp", is revealed. That's what you can see as a yellow line in the bottom plot. That's then tidied up even more.

There's still plenty to do. Most of the data from that first experiment hasn't even been published yet; that's coming in the next few days. Then LIGO itself will be tweaked and optimised to become even more sensitive before it starts its next data run in the summer. Then a 10-year programme of improvements and more LIGO detectors all over the world.

Because this result gives us an entirely new way to look at the universe and if we build more detectors, we can start to reveal much more about what is going on.

It's the dawn of a new age of astronomy and scientists at the University of Birmingham are at the heart of it.

- Published12 February 2016

- Published11 February 2016