Inside a very exciting and important boring machine

- Published

Elan Valley in mid-Wales. The water behind this dam is all destined for the taps of Birmingham

Deep under the Welsh and English countryside a team of engineers are working non-stop to keep the water supply to Birmingham working. It's a race against time and one mistake could mean the taps in Britain's second city running dry. So I've been deep underground to see exactly what's going on.

It's all to do with one of my absolute favourite pieces of Victorian engineering, Birmingham's water supply from Elan Valley.

Two Welsh valleys dammed and flooded and then a 73 mile (117km) aqueduct to Birmingham built to transport the water to a booming city. The water is fed under gravity using a gradual drop and a system of siphons to cross river valleys.

Cracks in the roof of the existing Victorian Elan Valley Aqueduct

It is a triumph of engineering, massive ambition and plain old Victorian showing off. Seriously, there are windows in one dam so you can look out and see the back of a waterfall when it spills over the top.

Elan now supplies more than five times the water to Birmingham that it did when it was built. That's around three hundred million litres of water every day. It's a tribute to the Victorians that the system they built to quench the city's thirst has been able to take this huge increase in demand.

It's even more impressive when you realise the Elan Valley Aqueduct, the pipeline connecting Wales to Birmingham, has had a very limited amount of maintenance in the more than one hundred years it's been in service. Since the aqueduct is Birmingham's only water supply when you close it for maintenance the city has to rely on its standby reservoirs and they only contain five days of water.

And since it takes a day to drain the aqueduct and then another to refill it there's actually only a three day window for any repairs.

Workers bolting new sections of tunnel wall in place as Nantmel Supermole moves forwards

These days it's the job of water company Severn Trent to look after the aqueduct and they have plans underway, external that will allow them to massively expand the current three day repair window. They are building an entirely new pipeline linking Birmingham to the River Severn. Once completed they will be able to switch all of Birmingham to this new supply for much longer periods of time and then get inside the Victorian aqueduct and give it some real engineering TLC.

Unfortunately there are three sections of aqueduct where cracks have appeared that will definitely take more than three days to repair but that also need fixing as quickly as possible and certainly long before the new link to the River Severn will be completed.

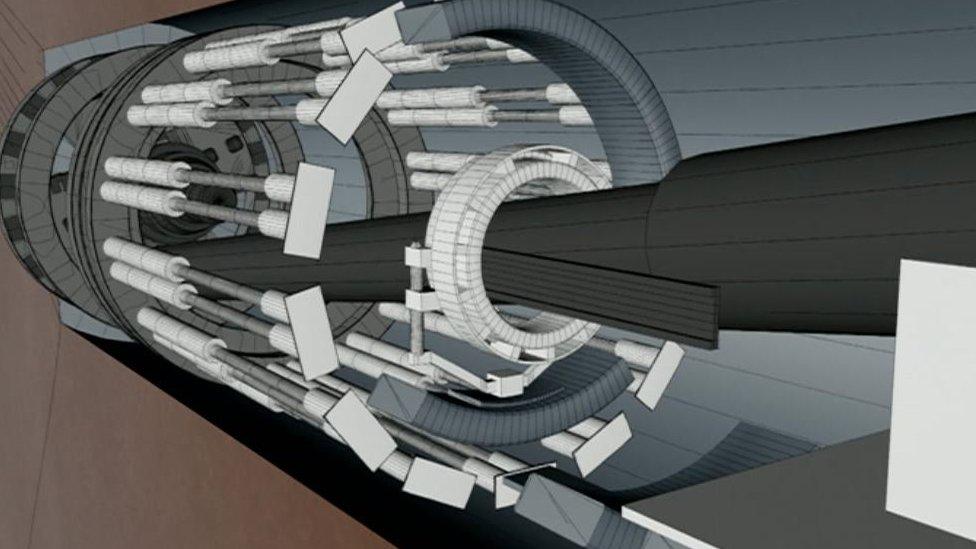

Massive boring machine

So the solution is a bypass. Build three completely new sections of aqueduct that go around the cracks and the problems and then link back up to the original Victorian structure. It's a £300m project, external and at its heart is Nantmel Supermole, a massive boring machine.

We were given the chance to go inside the Supermole and see how it works.

Inside the Nantmel Supermole drivers' cab

To get to the machine we had to take a small train along the kilometre of tunnel the Supermole has already dug. The train's main job isn't to save my legs it's to bring in parts to build the tunnel and take the tonnes of rock and soil out.

Arriving at the back of the Supermole we got out and then the train carried on to end up inside the machine so the empty trucks are in place and ready to be filled with soil.

At the back there's more than enough room to stand up, it's not too noisy and the air is pretty fresh and cool. But clamber towards the drilling end and it's a different story. You move forward on a very narrow gangway, squeezed between the wall of the tunnel and the machine itself. Space is tight and the further forward you go the tighter it becomes. I had to crouch down more and more, the noise from the drilling increases and it gets hotter and hotter.

Fortunately just as it started to get very uncomfortable I was able to squeeze myself into the Supermole's canteen. Yes, believe it or not since the crew are down here for 12 hours at a time they have a tiny canteen space. It's little more than a table with room for four people but there's a kettle and a microwave and a chance for me to stretch my legs out.

Above ground where the new section of tunnel will join the old Victorian aqueduct

Soon I pushed on to the very front of the boring machine. It is an extraordinary thing to watch. You can't see the actual rotating cutting disc that's boring into the rock, but you can see the giant hydraulic pistons that push the machine forward as well as steering it.

Suddenly the pistons began to retract and a robot arm started moving giant sections of tunnel wall into place. Each one locked into the other and workers swarmed around securing them in place.

Breakthrough day

Supermole, and those on board, have been working like this around the clock for four months but I was there on a very special day as Nantmel Supermole was due to re-emerge into the fresh air after four months underground. Everyone in the tiny canteen was studying a laptop showing the progress of the tunnel.

On the outside breakthrough is pretty spectacular as a massive rock face crumbles away to reveal the cutting disc at the front of the Supermole. But inside it's a very different story, in fact apart from the readings on the laptop changing I didn't even know we'd finally broken though.

This graphic shows the front of the Supermole. The giant rotating boring disc at the front. The pistons. And the robot arm just lifting a new tunnel piece into place.

Suddenly though Supermole fell silent (ish) and it was time to leave. But not the way we arrived, instead I was to be taken out the front of the 150 tonne machine and through the brand new hole it had created.

I will admit I was a bit nervous climbing up through this enormous piece of machinery. Suddenly as I crawled along I could see hints of daylight and hear the crowd gathered outside. It's a tricky job to clamber down and then out through a fairly narrow gap in the front of the Supermole (which I was suddenly very conscious was made to easily chew through rock never mind a squishy reporter) and into the noticeably fresh air.

This marked the end of the second section of new aqueduct and work on the third and final chunk is already underway. The hope is to have the refreshed Elan Valley Aqueduct all hooked up and in action by the anniversary of its original opening 115 years ago.

The worst case scenario is if anything goes wrong it could cause huge problems for more than a million people. But what's much more likely to happen is all this work will go swimmingly and building on the brilliance of the Victorian legacy will leave Birmingham with a water supply that will last another 100 years.

And most of the people in the city will never notice a thing. It's an engineering miracle we really do take for granted. And if you can't see the aqueduct itself, after all it is 18m (59ft) under the ground, a trip up to Elan, external is a chance to admire the ambition of the Victorians and also the engineers that have followed who continue to quench a city's thirst.