The racist nightclub ordered to change its entry policy

- Published

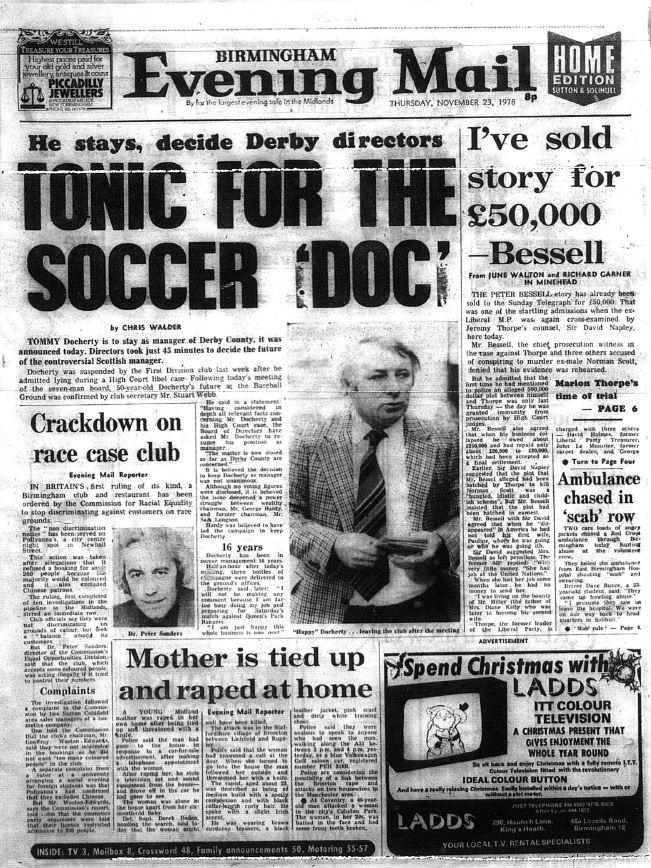

Pollyanna's in Birmingham was told to open its doors to all

Until 1965, it was legal to turn away black people from pubs or clubs simply because of their colour. But it would be more than a decade before a Birmingham nightclub was issued with the first non-discrimination notice of its kind, ordering it to open its doors to all.

In the spring of 1978, the inaugural Rock Against Racism (RAR) gig was held in front of tens of thousands of people, a movement that was inspired by a drunken speech by Eric Clapton, external at a gig in Birmingham two years earlier.

Yet in the same city, a popular nightclub was unashamedly turning people away on the grounds of race.

Months later in November 1978, Pollyanna's was ordered by the Commission for Racial Equality to open its doors to both black and Chinese people.

Regardless, it continued to enforce its door policy - flying in the face of movements such as RAR and despite the changes to the law, external enshrined in three successive Race Relations Acts.

"I think we have to limit all sorts of people, and coloured people fit into that category," the club's manager Jeffrey Weston-Edwards told the BBC at the time.

Walton Wilkins remembers going to the club in Newhall Street in the early 1980s.

He says he was made to sign in, while his white friend walked freely into the venue.

News of the crackdown on Pollyanna's made the front page of the Birmingham Mail

"When I got there first they said 'can you sign the book?' and I didn't think anything of it. My friend went walking in and I said 'you've got to sign the book' and they said he didn't have to.

"We just couldn't work it out and we saw it happen when another black guy came in - it was only the black people [who had to sign in]."

The experience, says Mr Wilkins, now 54 and still living in Birmingham, left him in "shock".

"It was my first experience of it going out," he said. "It was the first nightclub I had been to and it left a lasting memory."

While he never returned to the venue while it was still Pollyanna's, he recalls "it was well-known that it was an openly racist club".

David Hinds, lead vocalist of Birmingham reggae band Steel Pulse, also remembers the club's racist policy.

"I do remember going to Pollyanna's in the mid-70s. I went there, but it was an all-white nightclub at the time, probably had one of those 'limited amount of black people attending' [policies].

"Pollyanna's was a club known for that."

Birmingham reggae band Steel Pulse remembers the policy at Pollyanna's

The club was investigated after two separate complaints

But the situation wasn't just limited to Pollyanna's, with other clubs in the city having similar policies in the 1970s, Mr Hinds told BBC World Service's Witness programme.

"There was a lot of [those] scenarios happening in the clubs," he added. "Some of them weren't there in writing on a placard outside the club, but they were pretty much there.

"Some of the clubs had policies where there were no blacks or there were blacks that were of a limited amount, or we had to have a certain attire.

"Some clubs had the policy where you were only invited certain days of the week."

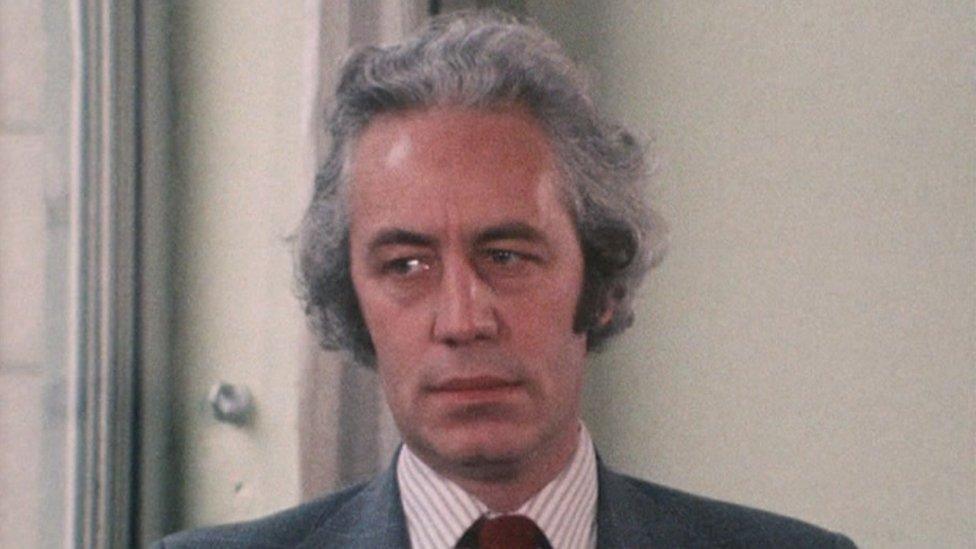

Jeff Weston-Edwards told the BBC at the time that the club must limit "all sorts of people"

Dr Peter Sanders was director of the Commission for Racial Equality (CRE) at the time Pollyanna's was issued the order, later becoming the organisation's chief executive.

He said the club's behaviour would have been "fairly common" across the country at that time, describing it as "fairly widespread".

Race relations in the 1970s were "much more raw than they are now", Dr Sanders said.

And it wasn't just clubs discriminating on the grounds of race.

"[There were] some employers who didn't employ blacks at all, and the way they did it was they recruited through word-of-mouth and that way, they said they 'kept themselves as one happy family'. So that way they didn't turn any blacks down for work, but blacks never applied."

At Pollyanna's, once the notice was issued, owners had to provide evidence they were complying with the order for two years, or face prosecution.

However, Mr Weston-Edwards said at the time that it would have no effect on the club.

He told the BBC he had to limit the numbers of ethnic minorities to preserve a "happy situation" and avoid aggressive confrontations.

"We will operate as we have done for the last 10 years in exactly the same way," he said.

Maxie Hayles has campaigned against racism in Birmingham for many years

Maxie Hayles, human rights activist, on life in 70s Britain

The 1970s was one of the worst times for racism we had in Britain as black people.

You not only had the recession under the various governments at the time, but what we had was the issues around racial terrorism - because it was terror - name calling and actual physical attacks.

The Race Relations Act was feeble. It wasn't an easy time for black people. The first act didn't address social issues such as social housing.

During that time, because the racism was so bad, there were very few places that black people were allowed because of the colour bar, so people had to resort to creating [their] own entertainment and places to go to.

The 1980s were when things began to change.

The investigation that eventually led to the non-discrimination notice had been prompted by two complaints against the venue.

The first was from the sales manager of a local cosmetics company who tried to book Pollyanna's for a Christmas party.

But the reservation was refused after bosses discovered a large proportion of the group were black.

In the second case, a university lecturer was told she could not take a group of students to Pollyanna's because they were Chinese.

Protests were held at DSTRKT club in 2015 over claims women were turned away due to their race

The club's management said they barred both white and black people if they disapproved of their attitude or the way they were dressed.

It's a method that is still being used on doors as a way of controlling entry, according to Kimberley McIntosh, policy officer at race equality think tank, the Runnymede Trust.

Controversial door entry policies are "not something that with time has changed as much as we hoped", she said.

More content from Black History Month:

Ms McIntosh cites the example of claims - which were denied - that London nightclub DSTRKT turned away women for being "overweight" and too dark".

And it is often the case that clubs use more discreet ways to police their doors and cases of "quite coded language to circumvent the law", she added.

"[We are] also seeing 'dressed appropriately', which is something that's used quite often now, even though people have followed all the dress code rules."

"Another recent one is [a] Grenfell fundraiser in Shoreditch," she said. "Once the [venue] found out the music would be urban, it was immediately cancelled, saying it would be a 'poor demographic'."

Ms McIntosh said it was an example of "linking certain types of music with a certain crowd and violence".

Kimberley McIntosh from the Runnymede Trust says people are still being discriminated against by nightclubs

As for Pollyanna's, after monitoring the club's race equality record for another year the CRE took the owners to court in 1979.

The court imposed injunctions stopping them from practising discrimination, and also ordered them to produce information to the CRE proving they had complied.

After the judgement, it emerged there was also a no-headgear rule at the nightspot which effectively excluded Sikhs as well.

This was not covered by the original non-discrimination notice, so the CRE had to go back to court to get the notice reworded.

An injunction was finally issued against this rule too.

Dr Peter Sanders was director of the CRE at the time Pollyanna's was issued the order

Dr Sanders said it is understood the club complied with the injunctions - although the experience of Mr Wilkins would suggest otherwise.

Pollyanna's eventually closed in 1987 when Genture Restaurants Ltd was dissolved - the building is now occupied by Michelin-starred chef Glynn Purnell's restaurant.

Ultimately, says Mr Hinds, the changes to, and enforcement of, the law had a positive impact on race relations in Britain.

"At the end of the day, for you to learn of someone's culture, it's always best to have it in a social environment and where else is better to learn of someone than in places where you can sit down and have a drink or have a meal, socialise by dancing, [or] by having conversations round the table?

"I think it was most important because for you to have races and cultures having an understanding and having racial harmony, those were the environments and the outlets that were accessible to all of us.

"You find once you are in an environment like that and you are socialising, people see it as a template that when it comes to other areas... jobs... housing... they realise that once you open the barrier for one thing, the barrier will be lifted in other areas.

"To me, it promotes racial harmony and this is what the world needs today."

- Published1 October 2015

- Published30 September 2015