The turban-wearing British bus driver who changed the law

- Published

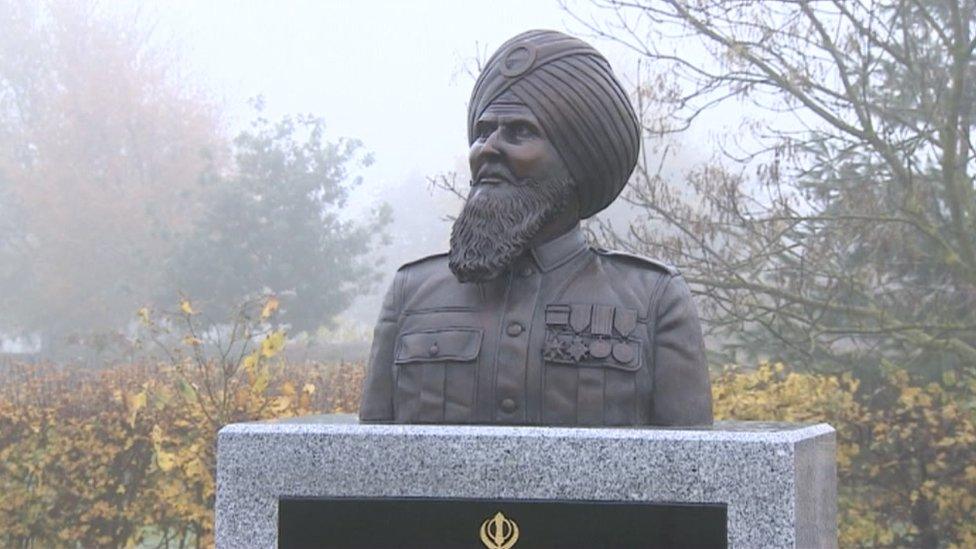

Tarsem Singh Sandhu fought for two years for the right to wear his turban to work

Fifty years ago, Sikhs working on Wolverhampton's buses won the right to wear the turban at work. It followed a long-running dispute during which one Sikh man threatened to set himself on fire.

It was a time when racial tensions there were high, with the city's most famous MP Enoch Powell saying the country was "heaping up its own funeral pyre" by permitting mass immigration.

The Express and Star newspaper reported the turban dispute "could bring chaos to the town's bus services", but it was not just public transport that faced upheaval.

Refusing to remove his turban or shave his beard, Tarsem Singh Sandhu sparked a row that spread across the world and saw the nation's racial tensions and identity politics played out on Black Country double-deckers.

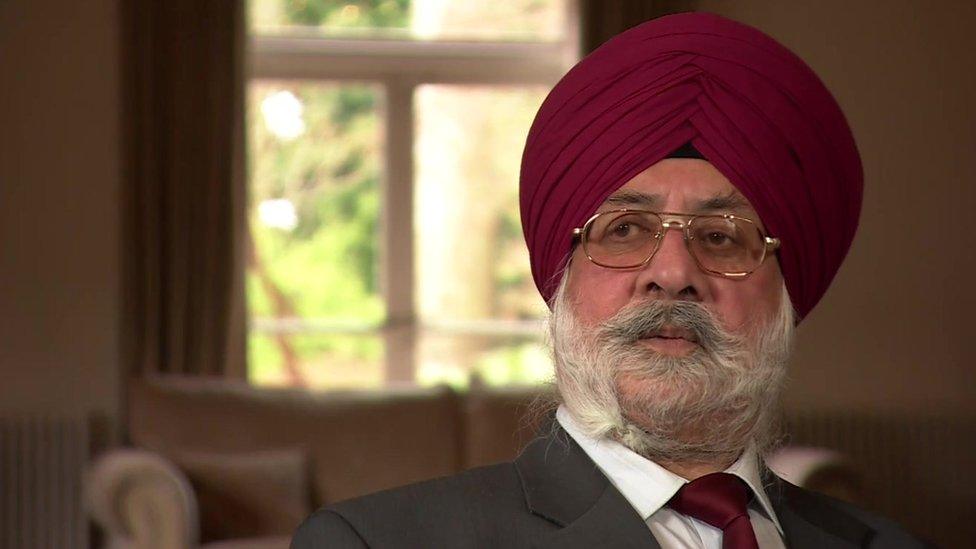

Mr Sandhu said he was proud he took on the bus company 50 years ago

"I couldn't see anyone in Wolverhampton at that time with a turban," remembers Mr Sandhu, who arrived in the Midlands in his 20s more than 50 years ago.

Wolverhampton was different back then, he said. He remembers the racism, the teddy boys, and when he plucked up the courage to wear his turban, colleagues wearing crude mockeries on their heads.

Soon after arriving, he was pinned down by uncles who cut his hair against his will.

He would never get a job with a turban, he was told.

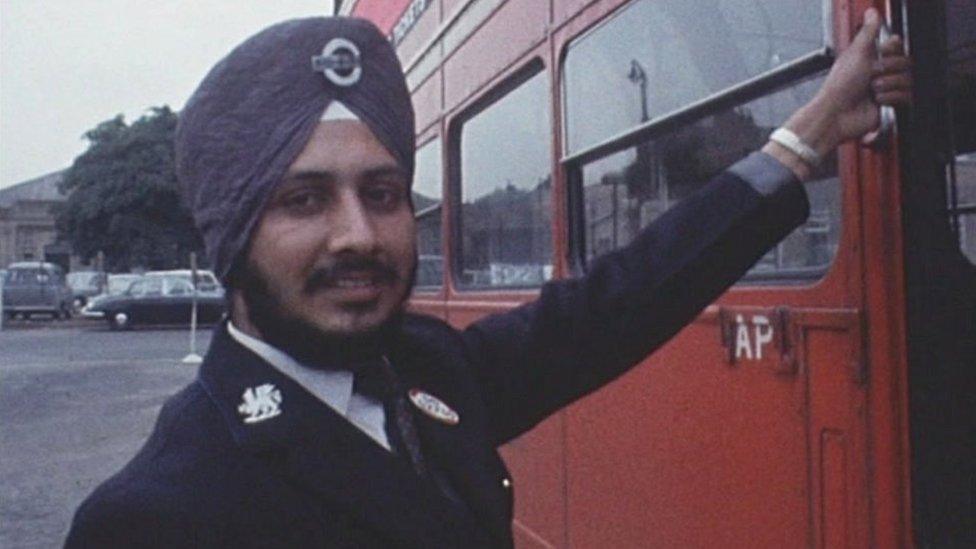

At 23, he began working as a bus driver with Wolverhampton Transport Committee which at the time employed 823 drivers, 411 of whom were Indian.

All had signed the uniform policy, agreeing to come to work clean shaven and wearing the uniform cap. None of them wore a turban.

Sikhs would shave and cut their hair in order to work on Wolverhampton's buses

After a short illness in 1967, Mr Sandhu returned to work complete with turban and beard.

Hair is one of the five Sikh articles of faith for the Khalsa - it must not be cut and is maintained in a turban - and Mr Sandhu decided he could not forgo his religion for the sake of a bus driver uniform.

After one round trip, he was sent home to shave. He refused.

"I never thought it would be as big a dispute as it was," Mr Sandhu said, "because there was nothing wrong with what I was doing."

About half of Wolverhampton's bus drivers were Indian at the time of the dispute

Fifty years on, a young turban fitter, Vikran Jaat Singh, said more young people than ever are wearing the turban.

Famously, in June last year, Charanpreet Singh Lall became the first Sikh guardsman to wear a turban during the Trooping the Colour parade.

"Before, everyone used to cut their hair," Mr Singh said, but he now runs a business fitting turbans for special occasions.

"If someone says 'go to work without your leg', would you?" he asked. "Turbans are part of us - you can't leave part of yourself behind."

Charanpreet Singh Lall became the first guardsman to wear a turban in 2018

What Mr Sandhu did, according to Opinderjit Takhar, director of the centre for Sikh and Panjabi Studies at the University of Wolverhampton, "is so significant to the lives of Sikhs here in the UK".

The former bus driver, who still lives in Wolverhampton, modestly said his actions, which went on to change legislation about religious expression at work, were "natural".

"He showed religion shouldn't take a back seat," Dr Takhar said. "As people realised they were here to stay, they realised they no longer had to compromise on their identity."

Wolverhampton bus drivers had to be clean shaven and wear a cap

After he was suspended in 1967, Mr Sandhu tried to gain the support of his union, Sikh community groups and local gurdwaras.

"They only had one thing to say," Mr Sandhu remembers. "No."

"Some [Sikh] people supported me; they thought we have done something wrong, we have made a mistake [by cutting their hair], but at least there is one young man who stood up for what is right and we must support him," Mr Sandhu said.

"Others thought 'we've come to work in this country and he's creating problems'."

Sikh soldiers wore the turban while fighting for the British army

He turned instead to the Shiromani Akali Dal - the principal Sikh political party of Punjab - and the president of its UK branch, Sohan Singh Jolly.

"He was a very strong character," Mr Sandhu said. He had been a practising Sikh all his life, serving as a police inspector for the British Raj in Kenya.

During the British Raj, turbans were accepted as normal. Millions of Sikhs fought for Britain during both world wars, forgoing helmets for their turbans.

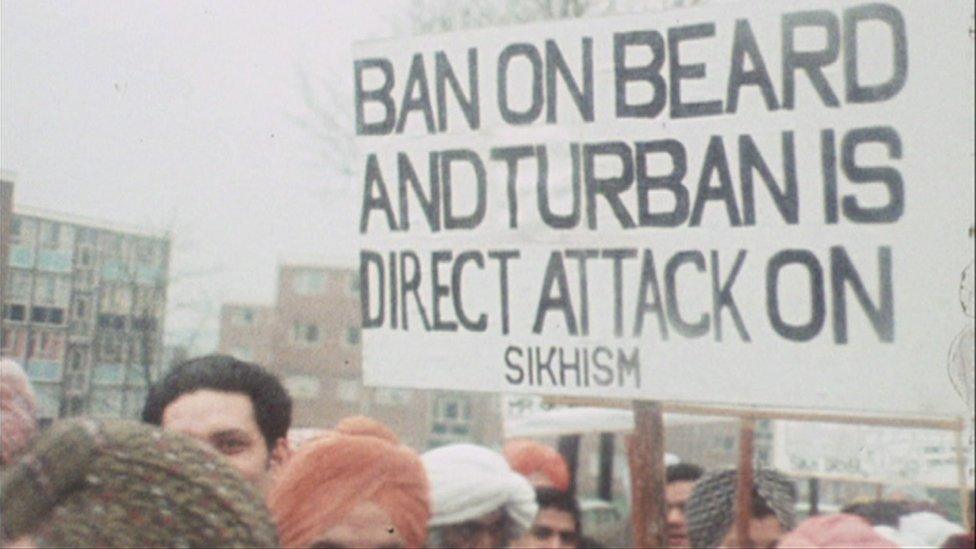

A march through Wolverhampton drew 6,000 Sikhs from across the country to the town hall, demanding change.

The message was also spreading overseas: A 50,000-strong march was organised through Delhi in support of Mr Sandhu and Mr Jolly.

About 6,000 Sikhs from across the UK marched through Wolverhampton demanding the turban ban be lifted

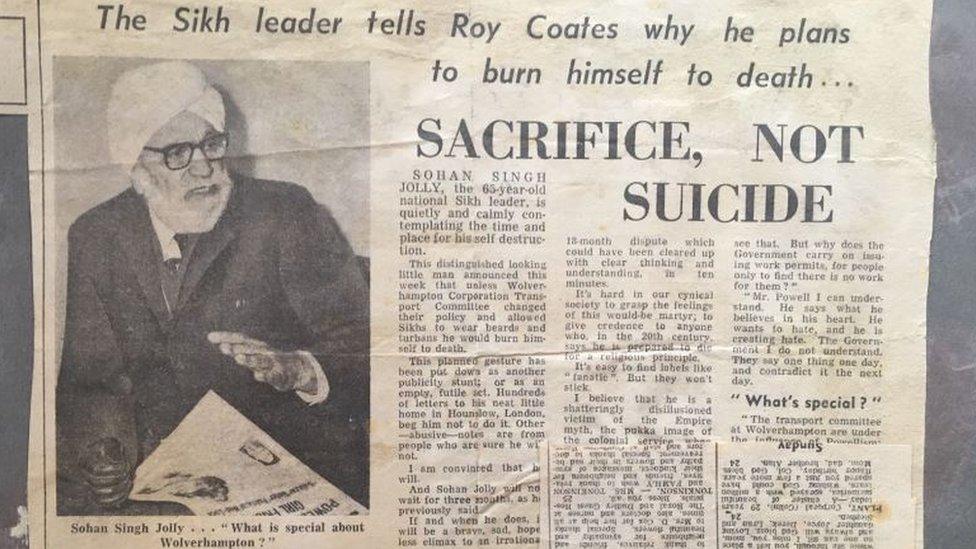

When nothing happened, Mr Jolly heaped pressure by making the ultimate threat.

"He said he would burn himself to death," Mr Sandhu said, "because it's not worth living in this country where the discrimination is that much."

Mr Jolly set a deadline of 30 April 1969 - the Sikh new year - for Wolverhampton Transport Committee to lift the ban on turbans.

"I am not frightened for anything," he said at the time. "I find it my privilege to sacrifice for the Sikh community."

Sohan Singh Jolly threatened to burn himself to death for Mr Sandhu's cause

But those on the other side of the dispute were also escalating their arguments, with one man in particular rallying support for the ban: Enoch Powell.

On 20 April 1968, moments before likening himself to the Roman witnessing "the River Tiber foaming with much blood", the MP for Wolverhampton South described the turban dispute as "a cloud no bigger than a man's hand that can so rapidly overcast the sky".

Powell was sacked after the now infamous Rivers of Blood speech, but his words had already had their impact.

People thought "he's come to this country he should do what this country does", Mr Sandhu said.

Powell received strong support from the public, with dockers and meat packers marching in support of him, and the local newspaper was flooded with letters supporting his speech.

Enoch Powell said the turban bus dispute threatened to "overcast the sky"

The Wolverhampton Transport Committee had found itself at the centre of a row which had outgrown the council house.

Buoyed by the public reaction to Powell's speech, the committee remained firm.

In 1968, its chairman Ron Gough told BBC News turbans were never likely to be seen on a Wolverhampton bus.

However, as Mr Jolly's deadline drew ever nearer, the pressure became intense and the ban was lifted on 9 April 1969.

The following day, an editorial in the Express and Star said the end of the dispute was "hardly a victory for anyone".

The argument, the paper said, had "made the name of Wolverhampton a sad by word for racial injustice and intolerance".

Wolverhampton is today home to the UK's second largest Sikh population

Mr Sandhu said the city had changed drastically since he was a young man.

Now, Sikhs are visible everywhere, he said, "freely going anywhere, doing any job".

Dr Takhar said Mr Sandhu "really put Sikh identity on the map" and made a "huge difference" in raising awareness of the turban's significance.

"It's thanks to him we have so many educated people, young people and women wearing turbans," she said.

Wolverhampton is now home to the UK's second largest Sikh population.

"Somebody has to take a stand whenever something is not being done right and put it right," Mr Sandhu said. "I was proud I did that."

Follow BBC West Midlands on Facebook, external, on Twitter, external, and sign up for local news updates direct to your phone, external.

- Published12 November 2017

- Published9 June 2018

- Published1 November 2015