Covid-19: The speech therapists helping patients find their voices

- Published

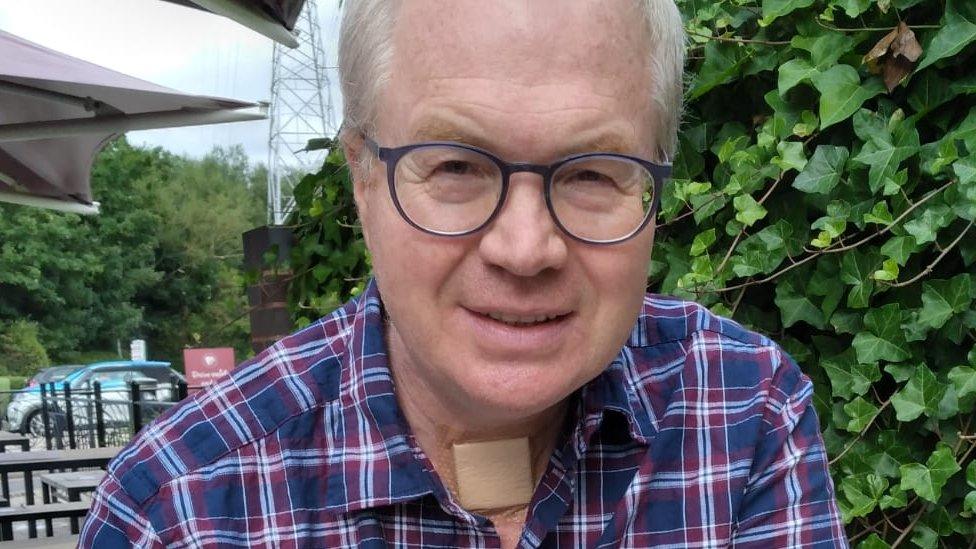

Robert Crowther is among thousands of patients rehabilitated by speech therapists

"I was very, very ill. I had lost the ability to swallow - one of my vocal cords had been paralysed by the ventilator.

"It was clear I'd fought off Covid, but now I couldn't speak."

Robert Crowther had just woken up in intensive care where he had been unconscious for a month.

A civil engineer, the construction site he was working on in the Midlands remained in operation as the UK went into lockdown last March. Within days of complaining of a headache, he was fighting for his life in a Birmingham hospital.

While coronavirus itself left its mark on Robert with a persistent serious chest infection, it was the effect of weeks in ICU that caused the most lasting damage.

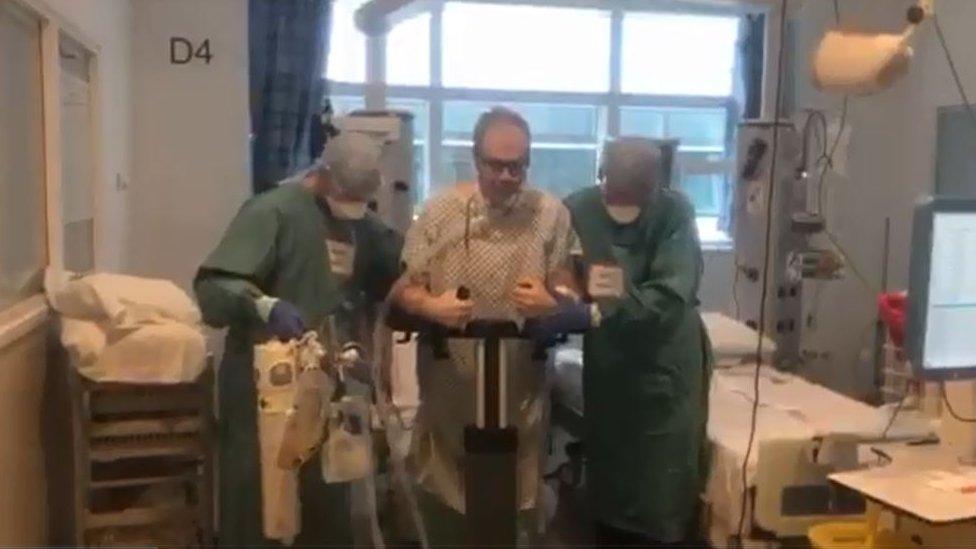

Muscle wastage from lying on a bed meant he was unable to walk. But the impact of tubes from a mechanical ventilator that kept him breathing for weeks, and a tracheostomy to allow air into his lungs, left him unable to talk, eat or drink.

Robert is among thousands of patients rehabilitated by speech therapists, the often hidden front-line workers who have continued tirelessly throughout the pandemic to help people regain the most basic of human functions.

Robert could only communicate with hand gestures and head movements after regaining consciousness

After weeks away from his panic-stricken wife Andrea and son Henry, 17, the inability to communicate after regaining consciousness was more isolating that ever.

"If the nursing staff asked me a question, they could sometimes lip read what I was trying to say, but I became frustrated when I could not make myself understood.

"I could answer yes and no by head movements. I could only attract their attention if they happened to be looking my way."

The civil engineer took a holiday with his wife and son after a long battle with coronavirus

Robert learned to walk again quite quickly with the help of physiotherapists, but it was the speech therapists at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital (QE) who became the main players in his recovery.

Back in spring 2020, the consequences of coronavirus were still being learned in hospitals across the world. Dr Camilla Dawson, the QE's consultant speech and language therapist, and many of her colleagues had worked through the swine flu epidemic of 2009, so had an idea of what lay ahead.

"Whilst we could predict what the complexities of the disease might have been, the huge volume of patients was not something we could have predicted, and the pressure that had on our clinical services," says Dr Dawson.

As the first wave took hold and the QE's ICU filled up with the seriously ill, the 25-strong team began the most intensive work of their careers. There has been little respite for them since; the impact of the second wave seeing the intensive care unit go way over capacity with Covid patients alone - more than 100 sufferers of coronavirus at times when there are usually 75 beds in total.

Dr Camilla Dawson said speech therapists around the world had been sharing knowledge as they learnt to cope with the challenges of coronavirus

Across the country, therapists who would work with outpatients have had to cancel everything but emergency treatment - many were drafted in to work in critical care in full PPE and have been there since the start of the outbreak.

"We are working different shift patterns, longer hours and weekends," says Dr Dawson. Everyone is feeling the pressure of working at the front line of a global pandemic. "We work hard to make sure people can emotionally process what's going on," she adds. "This is, fingers crossed, a once in a career time. We are all looking out for each other.

"The compassion and responsibility is unshakeable in the NHS. You can't see our faces at the moment, but we are still holding people's hands."

Many patients have a long recovery ahead - 60% of those who have been intubated for at least seven to 10 days have problems swallowing. The function of the voice box can be ravaged, vocal cords severely damaged.

For those who cannot swallow, the main focus is to prevent aspiration pneumonia - food or liquid could go down the windpipe and cause a severe infection.

"They'd give me a teaspoon of water but it was going down to my lungs," remembers Robert. When he could swallow a little water, he moved on to the tiniest amounts of crushed ice and yoghurt.

Other exercises might include working on swallow strength, work to improve the strength and stamina of the voice and to reduce tension in the throat.

Physiotherapists helped Robert learn to walk again after weeks lying on a bed in ICU

Amid the relentlessness of working long hours on packed wards, there are moments of pure joy for both patients and staff, often when they finally feel able to video-call their worried loved ones.

"They held my phone and could lip read what I was trying to say and spoke for me," says Robert, who was persuaded to call despite being unable to talk well.

"Andrea and Henry were delighted to see me and it helped them to realise that I was recovering and would be coming home."

After 45 days in ICU and several more weeks on a ward, Robert was able to go home, albeit with a feeding tube. By the third week of August, five months after he contracted Covid-19, he was able to eat and drink properly again. He continued seeing the speech therapy team and in November last year, his voice "just came back".

Robert says he feels "very grateful" to the people who helped him speak, eat and drink again.

"You know they're important to you but you don't realise how life-changing they are until you lose them; this has made me realise it is."

Kamini Gadhok, chief executive of the Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists, is proud of her colleagues across the world

Thousands of survivors of Covid are continuing to have speech therapy sessions after being left with long-term problems. The NHS website Your Covid Recovery, external helps sufferers identify voice and swallow issues.

"It's a far more complex virus than we originally imagined," says Kamini Gadhok, chief executive of the Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists. "We are still learning about patients' recovery but we are doing really well as a profession to pick things up and learn from it."

Therapists around the world are clocking off shift and sharing knowledge with each other. "I'm very proud of them," adds Ms Gadhok.

"It makes me want to weep - they work these incredibly long hours and then want to do a webinar so we can learn more about it."

Dr Dawson, an expert in critical care for the Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists, describes her industry's work as "unique".

"Eating, drinking and communicating are core and innate parts of being human," she says.

"These functions enable us to connect, to be with people and share experiences, central to our cultures and the way we interact with society."

Seeing people recover is the most rewarding part of the job, not least those who have managed to beat coronavirus.

"We are with people through the toughest, most isolating time. It's the most overwhelming feeling to know how hard an individual has worked and how much opportunity they will have as a result of their treatment.

"You are over the moon for them - it's the most wonderful thing."

LOOK-UP TOOL: How many cases in your area?

YOUR QUESTIONS: We answer your queries

GLOBAL SPREAD: How many worldwide cases are there?

THE R NUMBER: What it means and why it matters

TEST AND TRACE: How does it work?

Follow BBC West Midlands on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to: newsonline.westmidlands@bbc.co.uk , external

- Published5 February 2021

- Published3 July 2020

- Published25 January 2021