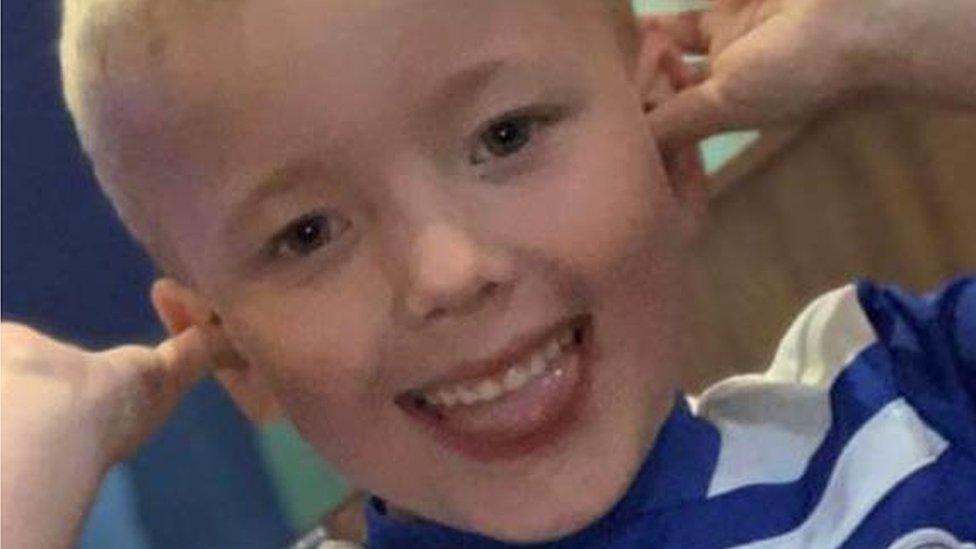

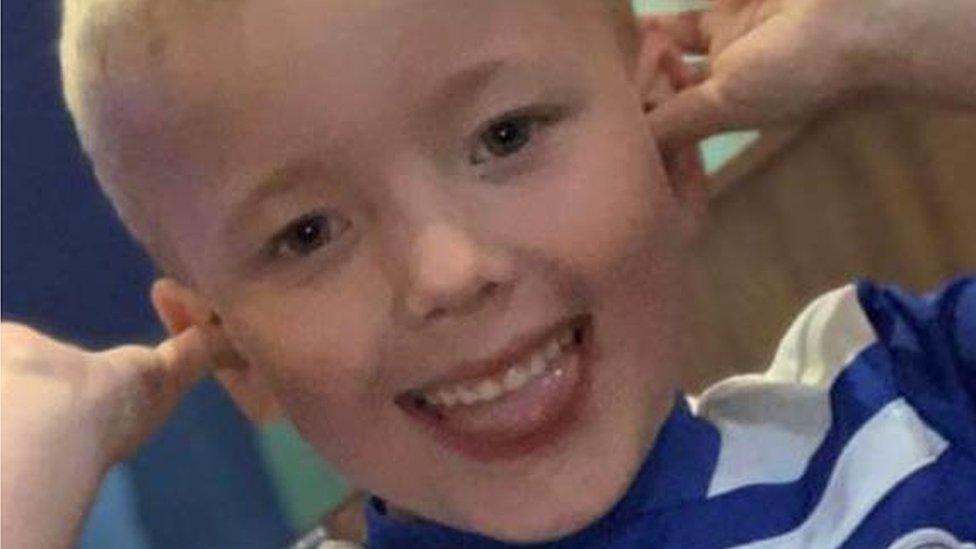

Solihull: Arthur Labinjo-Hughes report uncovers help delay

- Published

Two reviews have been commissioned into Arthur Labinjo-Hughes' death, with the local inquiry's findings published on Monday

Vulnerable children living where schoolboy Arthur Labinjo-Hughes was tortured and killed have to wait too long for help, a report has found.

Arthur, six, died in June 2020 following a campaign of violence by his father and stepmother.

A probe of services in Solihull has since uncovered a "significant" number of children who remain in "unknown risk" due to assessment delays.

Solihull Council said it had already begun improvement work.

The report, external, published on Monday, found "too many children in Solihull face drift and delay" under the support framework delivered by multiple local agencies.

Watchdogs said provision was "under-resourced" and showed a lack of "clear understanding" of the experiences of "children and their families that need help and protection".

In December, Emma Tustin was jailed for at least 29 years for Arthur's murder while her partner, Arthur's father Thomas Hughes, was given a 21-year sentence for manslaughter.

Emma Tustin took a photo of Arthur as he lay dying and sent the image to Thomas Hughes

The pair's trial heard Arthur had been poisoned with salt by Tustin and subjected to regular beatings by both adults. He was also given punishments such as being denied food and drink and being made to stand for hours alone in a hallway.

Tustin delivered a fatal head injury to Arthur while in her sole care.

During the trial, it emerged social workers from Solihull Council had visited the boy's home in the months before he died and found no issues, despite relatives raising concerns.

A national inquiry commissioned after the pair's sentencing is to focus on the precise circumstances of the case. In the meantime, a Joint Targeted Area Inspection (JTAI) last month probed how local agencies worked together to help children.

'Highly reluctant'

The JTAI found Solihull's Local Safeguarding Children Partnership had experienced frequent changes of personnel which "resulted in a loss of knowledge and experience".

It warned long-standing issues in ensuring there were enough social workers had been compounded by Arthur's death, making those in the profession "highly reluctant to work in Solihull".

Additionally, inspectors were "concerned" about record-keeping flaws within the police system, including multiple records for the same person, and children not linked on the system to their parents, carers, siblings, and those who may pose a risk.

Inspectors identified one case of a child who was not linked to her father who had a criminal record, meaning an incident of domestic abuse to which the child was exposed did not appear on her file.

The report also found health workers did not have access to each other's records.

Learning from significant incidents was not shared effectively either, it added, although steps had been developed following Arthur's death, it said, including guidance on bruising to children.

Arthur had more than 130 bruises when he died.

Analysis by Alison Holt - Social Affairs editor

Too many children experience "drift and delay" in having their needs, and risks they may face, assessed in Solihull.

It's a stark conclusion from the inspectors as they try to provide context to why concerns raised about Arthur Labinjo-Hughes didn't lead to more action.

Knowing when to step in to protect a child is an incredibly tough judgment call. Information is almost inevitably patchy, but the inspectors describe the front door of Solihull's child protection services as significantly under resourced.

It points to immense pressure to meet daily demand, not enough social workers and long-term systemic issues, including delays in getting early support to those who need it.

Such pressures are not unusual. Many children's services teams in England say they are dealing with growing need and struggling to recruit staff.

Years of squeezed council budgets mean there have been significant cuts to the early intervention services which might head off later problems.

There is a government review into the whole system currently under way, and many will argue that these deep-rooted problems have to be addressed if children are to be better protected.

Inspectors said Solihull Council should prepare a written statement of proposed action by 30 May.

A raft of measures were suggested by inspectors. Steps, they said, should include addressing the "timeliness and quality" of initial decisions relating to concerns raised about children, and boosting consistency in recording children's voices across all agencies' records.

The local authority said it had already launched an Improvement Board and recruited an independent chair to work on upgrading safeguarding in the borough.

Council leader Ian Courts, Conservative, said the new improvement board would "support, oversee, and importantly challenge" organisations with responsibility for safeguarding children.

Opposition councillor Marcus Brain, Green, said: "A lot of this seems to come down to quite fundamental systemic failures across the various multi-agencies."

Arthur had more than 130 bruises when he died

In a joint statement, the Minister for Children and Families Will Quince, the Minister for Care Gillian Keegan, and Minister for Safeguarding Rachel Maclean, said: "Arthur's death was horrific and deeply disturbing.

"The two individuals responsible are in prison - but we must do everything we can to prevent any more cases like this. His death serves as a daily reminder of the urgent need for all the agencies tasked with protecting vulnerable children to work together."

They said police, health and children's services had an "equal duty" and they would be writing to all three about their expectation the agencies would provide a statement of intent.

Arthur had lived with his mother Olivia Labinjo-Halcrow until 2019

Arthur had lived with his mother Olivia Labinjo-Halcrow after she and Hughes split up not long before the boy's second birthday.

In 2019, after she was jailed for the manslaughter of her partner Gary Cunningham, Arthur was left in the sole care of his father.

The sentences of Tustin and Hughes have been referred to the Court of Appeal by the Attorney General as she believed they were "too low".

Arthur's case prompted an outpouring of grief across the UK and, after his killers were jailed, hundreds attended a vigil near the home where he died.

Follow BBC West Midlands on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to: newsonline.westmidlands@bbc.co.uk , external

Related topics

- Published31 December 2021

- Published6 December 2021

- Published6 December 2021

- Published5 December 2021

- Published5 December 2021

- Published4 December 2021

- Published3 December 2021

- Published2 December 2021