Bristol Harbour Festival: How a city's main attraction was nearly lost

- Published

Street theatre and music are now a huge part of the festival

This weekend an estimated 250,000 people will brave the heat to enjoy the Bristol Harbour Festival, one of the highlights of the city's summer calendar.

As they watch the tall ships, live music and water displays, many may not realise that there was once a plan to put roads and buildings over what is now Bristol's main attraction, and that the festival itself was created as a weapon to fight against it.

By the mid 1960s, Bristol was well on the way to recovery following the devastation of the Blitz more than two decades earlier.

The opening of the M4 and M5 motorways and the construction of the then-new Severn Bridge had boosted the city's status as a regional centre for business.

A dramatic change came in 1969 when the city council announced it was closing the docks, which had been losing business to Avonmouth for some time. The council owned Bristol's docks, and was planning a new development at Portbury.

What to do with the waterway was the obvious question. Roads and buildings was the answer in the minds of some council planners.

Bristol Docks, seen here in 1921, had faded in terms of importance and revenue by the late 1960s

As Bristol historian Eugene Byrne recalls, that decision sparked some of the most frenzied campaigning the city had seen in the 20th Century.

"In August 1969 the council proposed a Parliamentary bill withdrawing navigation rights from the docks," he said.

"It spoke of bringing in a 'lagoon system' for parts of the Floating Harbour, and reclaiming the Feeder Canal.

"In other words, parts were being covered over, or filled in."

But as the council took this bill to the House of Commons, long-established and new campaign groups in Bristol took up the fight against it.

The Bristol Civic Society and the Council for the Preservation of Historic Bristol were joined by newcomers the Clifton & Hotwells Improvement Society.

The names of the people in the fight are well-known to older Bristolians. Jerry and Anne Hicks, who have since died, were key figures. As was George Ferguson, who went on to become Bristol's first elected mayor in 2012.

One obituary for Mr Hicks described him as "the saviour of Bristol's docks"., external

Despite their efforts, and those of many others, Mr Byrne said, the Bristol Corporation Bill was passed by Parliament in 1971. The council seemed to have won the day.

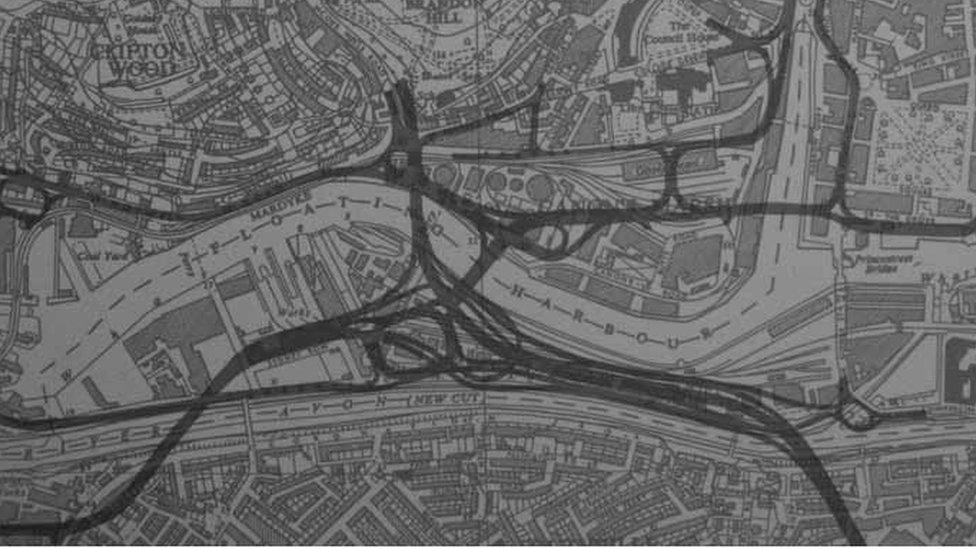

A large new road network over the docks was part of the proposals put forward in the early 1970s

But they reckoned without an intervention from an unlikely source.

Casson, Conder and Partners - one of the leading architectural practices of the day - was called in to assess the best use of the various pieces of the harbour.

And their findings, in what became known as the Casson Report, blew a hole in the council's arguments.

From humble beginnings, the festival has grown to become the biggest in Bristol

Describing the harbour as a "shining wedge of water", it criticised the prospect of a major road network running over the docks, and suggested a more community-focused future.

"The waters of the harbour, used to unify and to separate, to enliven and relax - should return to the citizens for their enjoyment: the wharves and banks to be opened up for boatyards, marinas and waterside promenades with the restored Great Britain as the magnificent centrepiece," was perhaps the most stunning line of the report.

"While the rebellion against concreting over the docks was often led by the professionals in the amenity societies, this was never a purely middle-class movement," said Mr Byrne, author of Unbuilt Bristol: The City That Might Have Been.

Large concerts on the water's edge are now a regular part of the weekend

"The local press, particularly the Evening Post, gave huge amounts of coverage to the issue and its letters pages acted as a forum for public discussion.

"The destruction of the docks and the loss of heritage was a powerfully emotive issue for Bristolians of all classes," added Mr Byrne.

That passion was demonstrated when 200,000 people lined the banks of the Avon and the harbour to watch the return of Brunel's SS Great Britain to the city in July 1970.

A new festival emerges

While the political battle over the docks raged, a new event took place over the weekend of 26-27 June, 1971.

Originally called the Bristol Water Festival, its main aim was to show that the inland waterway of the city was a perfect location for people to enjoy leisure.

The first festival took place in June 1971

The late Fred Blampeid, who was the chairman of the Inland Water Association South West Branch, said at the 40th anniversary of the festival: "As part of the original committee who started The Bristol Water Festival, it's fantastic to see how far it has progressed.

"We successfully managed to demonstrate the leisure and amenities use around the harbour and better still it is now the central point of the city.

"The festival has something for everyone nowadays, and it's great to see the hundreds of thousands of people who come every year enjoying the harbourside."

The first event, in 1971, was called the Bristol Water Festival

The original event, billed as a rally of boats against the council's plans, was very small scale compared to what it has become, and featured events such as a tug-of-war on the water.

A new era begins

As the 1970s wore on, the Harbour Festival grew and the political landscape began to shift.

The pressure to build new roads and houses faded, recession came and went, and in the end, the plans to carve up Bristol's docks faded.

"The council-owned Port of Bristol Authority handed responsibility for the city docks over to the council on 1 April 1975 and city officials recommended abandoning the 1971 Act, which they did the following year," said Mr Byrne.

"The Arnolfini art gallery, which many like to claim led the regeneration of the docks, moved into Bush House in 1975."

The sight of hundreds of people sitting on the dockside outside the Arnolfini on a summer's evening is as "Bristol" as hot air balloons and street art.

Vessels of all shapes and styles fill the harbour during the festival weekend

This weekend, as the crowds return after Covid and the Harbour Festival celebrates its delayed 50th Anniversary, having last been held in 2019, the idea that what is now the jewel in the city's crown could have once been lost seems unthinkable.

In fact, Bristol City Council, having once proposed building on the docks, is now the main organiser of the festival.

The authority uses it to showcase the best of the city's arts and music scene, and has kept it free to enter.

And what began with amateur canoe races and sailors showing off their rigging-scaling skills now features food markets, live music on multiple stages, street performances, dance stages and much more.

Vessels of all kinds remain at the heart of the event, with more than 250 coming to Bristol to help with the special celebrations.

Kathryn Davis, Director of Tourism at Visit Bristol, said: "Research clearly demonstrates the importance of the harbourside in the visitor experience of Bristol, with 72% of all visitors associating the harbour with their trip.

"This is as much for international visitors as those from with the UK - regardless of the purpose of their visit.

"From a destination to enjoy sports, either as a spectator or participant, to dine, for culture and heritage or just a walk, Bristol's harbourside is an essential part of a visit."

Follow BBC West on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to: bristol@bbc.co.uk , external

- Published9 July 2022

- Published14 March 2022

- Published14 April 2021

- Published19 July 2015