Rugby concussion: Justin Wring 'terrified' after dementia diagnosis

- Published

Former rugby player Justin Wring describes the impact of a dementia diagnosis on him

Lawyers representing more than 185 former rugby union players have begun legal proceedings against the sport's governing bodies over brain damage suffered by their clients. Many of the people involved are household names, like English World Cup winner Steve Thompson and Welsh international Alix Popham.

One man also in the legal papers, but less well known, is former Bristol, Leeds and Stade Francais prop Justin Wring. He can still remember helping the French side to a last-minute title win in 2000. The story of how his life has unravelled since then is no less dramatic, however.

Stade Francais were 28-23 up in front of more than 80,000 fans in Paris in a winner-takes all contest, but Justin Wring's side faced disaster in the final minute.

Camped on their own line with opponents Colomiers flooding forward, Stade were penalised and a scrum given against them. A man down, they faced being shoved backwards or stretched until Colomiers scored the try that would give them victory.

Step forward Wring, whose almighty shove at the scrum led to a sharp blast on the referee's whistle, a penalty for Stade and victory. The Bristolian can still remember the wild celebrations in the stadium.

"Apart from my marriage, that's the highlight of my life," he said.

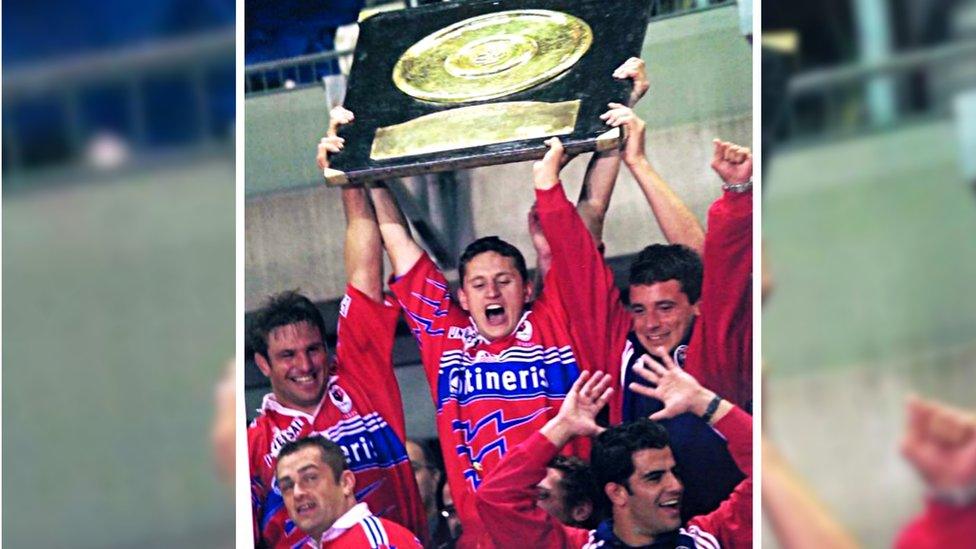

Wring was introduced to then French president Jacques Chirac before the title-winning match in 2000

Winning the French title in 2000 was Wring's career highlight

England international Steve Thompson played in every game of England's 2003 World Cup winning tournament, but says he cannot remember any of them.

Wring, 50, still has his most cherished playing memories, but, having been diagnosed with early onset dementia like Steve Thompson, also knows he may lose them.

He says he can now leave the house to visit the chemists around the corner and lose two hours, ending up outside his front door again unsure of how he got there.

He once found himself in the middle of Broadmead in Bristol city centre, standing in the road with a bus bearing down on him, his mind blank.

"The driver was shouting and swearing at me. Luckily my wife was nearby and came and got me."

Wring says seizures, depression and anxiety now mean he rarely leaves his house in Keynsham, unless someone he trusts is with him. His life, he says, has been an ordeal since 2008 when his medical problems first began.

I would have loved to have stayed [at Bristol] throughout my career.

His career started with a boyhood dream being realised. Having begun playing while a pupil at St Mary Redcliffe School in Bristol, and in the Barton Hill neighbourhood, Wring earned a reputation as a strong prop, and eventually had a successful trial at his home city club.

"That was a dream come true," he remembers of being able to pull on a Bristol jersey.

It didn't work out in the long term, because when the club was promoted to the Premiership in the late 1990s, they wanted more experienced props, and Wring found himself looking for another club, although he would return to Bristol for a spell in the mid 2000s.

"I would have loved to have stayed [at Bristol] throughout my career," he said.

But as one door closed, another opened. While on a family holiday in Cyprus in 1999, he took a call from former Bristol team-mate Fabrice Landreau saying Stade Francais wanted to sign him.

"They were one of the biggest clubs in France at the time. It was a no-brainer," said Wring.

"Scrimmaging was a huge part of their game, so it suited me. I had to learn the language and learn about how they played, but I worked hard."

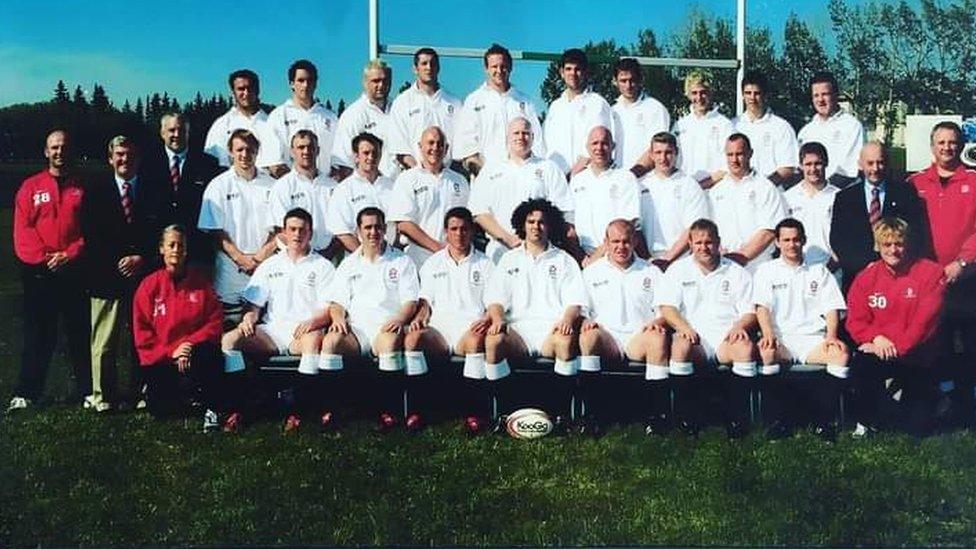

Wring (back row, third from left) was once selected for the England Counties side

He had only been there a year when that magical moment in Paris came.

"It was amazing to be part of. Not just being part of the squad but being on the pitch at that moment. It was fantastic," recalls Wring, whose last-minute heroics in the title-winning match earned him another contract with Stade.

He eventually left France, spent some time playing for Leeds, and then - when a leg injury cut his career short in 2008 - started planning to set up his own fitness business.

And then things began to go downhill.

'Screaming in the street'

It started with what he calls a "huge breakdown" not long after he stopped playing. Depression followed, accompanied by a series of dramatic events.

He once ran screaming into the street in the middle of the night, and had no idea why. At his lowest points, he tried to take his own life twice and spent time in a psychiatric ward.

"I just kept thinking 'something's not right here'. Nothing ever seemed to get any better.

"I was put through all sorts of psychological treatments, took anti-depressants - nothing worked."

More information about dementia and details of organisations that can help can be found here.

Between 2008 and 2015, he describes his life as "just awful". With him unable to work, Wring and his wife Charlotte lost their house and moved back to live near Bristol, where at least he had the support of his family.

In 2015, the seizures began. Wring says he had MRI tests, but they couldn't get to the bottom of what was going on.

"They called them non-epileptic seizures. They couldn't find any brain damage on the MRIs, so they said I was fine in that sense.

"They [the doctors] were looking at me wondering. I think they were just guessing, really."

In late 2019, Wring was contacted by fellow player and Welsh international Alix Popham, who was diagnosed with early onset dementia at the age of 40.

"He said he had heard I was struggling, and asked me what was going on. I just blurted it all out, 13 years of struggle.

"He told me 'there are others like you'."

Popham's intervention led to Wring finding out about a growing field of research into the impact of regular concussions and sub-concussions on rugby players.

Welsh international Alix Popham was instrumental in Wring's dementia being diagnosed

With the help of Popham and others, Wring was sent for tests at King's College in London.

"They found there was damage in three separate parts of my brain, the worst being at the front.

"My brain had also shrunk. I was diagnosed with early-onset dementia."

That diagnosis, Wring admits, was a "double-edged sword". He finally had an explanation for the problems that had plagued him since 2008. But now he also knew what he faced.

"I worry about my wife, as she will have to look after me more and more," he said.

"What really scares me to death is forgetting who my loved ones are. Not knowing who my wife or my family are - that absolutely terrifies me."

'Nobody talked about concussion'

Wring describes himself as a "rough and ready pro" who was into building his strength as much as he was learning the skills of rugby. Playing as a prop, being able to outmuscle his opposite number was one of his priorities.

Even if he had not been diagnosed with dementia, playing rugby would have still left a huge impact on his body. He has had surgery on both knees, a lacerated thigh muscle, a damaged groin, an operation on his neck to relieve pressure on his spinal cord and once broke seven ribs in a game.

He was willing to accept all that, he says, but not what is happening to his mind.

"People have said to me that I knew I was playing a physical game, that I must have expected to get injured," said Wring.

"Absolutely, I did expect that to happen, and my body is wrecked. But nobody said there was a chance I would get dementia within a decade, nobody was talking about concussion.

"When I played you would get plenty of bangs to the head, but you carried on.

"If you ended up going off, or wanted to go off because you weren't feeling right, you would be looked on as weak, they wouldn't trust you."

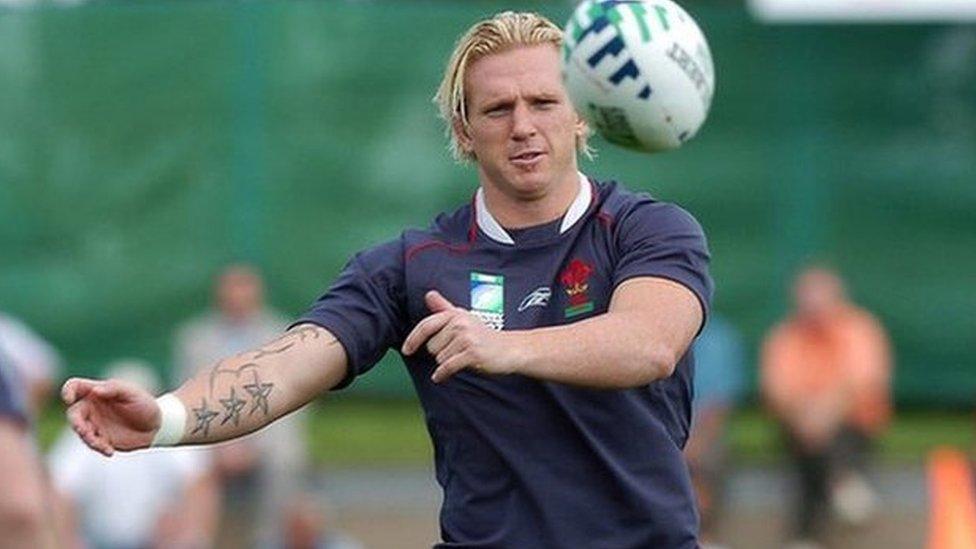

Former England player Steve Thompson says he cannot remember playing in the 2003 World Cup Final

Wring recalls being at one of his clubs when they lost a close game because one player missed a tackle.

"We were told to meet in the local park at 6am, and we did a full contact session for hours."

It was training sessions like that, as well as the matches, that Wring believes are behind the damage to his brain.

"We would sometimes train three times a day, with contact [tackling] in two of them. And in those training sessions they would be just as hard as the matches, as we would be trying to impress the coach."

'Look after my wife'

Perhaps inevitably, Wring has a complicated relationship with rugby, a game he loved but one he feels has left him in a very dark place.

He says he cannot watch games any more.

"I look forward to it, but I have to switch off after a few minutes and follow the score some other way. It's an anxiety thing."

The lawsuit against the rugby authorities will, he hopes, not only provide compensation so any care he might need can be covered, but also bring about fundamental changes in the sport.

"If I die early, I want to know my wife will be OK. That's more important to me than anything," said Wring.

"I also want to see changes. You're never going to get rid of tackling in rugby, but I think it should be made as safe as possible.

Elite rugby has to hit the reset button right now because these are the players in the shop window of this great sport.

"In football, you've got players getting dementia in their late 60s and 70s. But you've got rugby players getting dementia and brain conditions in their early 40s, sometimes their late 30s.

"That can't be right."

A player safety lobby group has called for rugby's authorities to make radical changes now, external.

Progressive Rugby's Professor John Fairclough said: "Elite rugby has to hit the reset button right now because these are the players in the shop window of this great sport.

"There is now no other option but to drastically reduce the number of impacts a player receives over their career and take extreme caution with the management of players who do suffer brain injuries."

'We never stand still'

A World Rugby Spokesperson said: "World Rugby appreciates that it will have taken great courage for Justin to speak so candidly about his personal circumstances. It is always tough to hear stories of this nature.

"We care deeply about every member of the rugby family and constantly strive to safeguard and support our players, driven by a clear commitment to further cement rugby as the most progressive sport on player welfare.

"Rugby is a leader in sport in the identification, prevention and management of head injuries, always acting on the latest science, evidence and independent expert guidance.

"We never stand still and proactively fund research, embrace innovation and explore technology that can make the sport as accessible, inclusive and safe as possible for all participants."

The spokesperson also said there was a "wide range" of support available to former players including free brain assessments and access to experts.

"It is also important to stress that elite rugby is a very different experience to the community game and that rugby remains a sport which provides benefits to millions of people all around the globe.

"We will continue to do everything we can to look after our players and former players because rugby is a sport with such positive health and wellbeing benefits and you don't leave the rugby family when you hang-up your boots," they added.

Players now have to leave the field for Head Injury Assessments (HIAs)

The RFU also said it was "deeply saddened" to hear Wring's "brave and personal account".

In a statement the organisation said: "Our thoughts are with him and any other player in this situation.

"We care deeply about both current and former players and will continue to use our many years of research and monitoring to improve head impact and concussion surveillance, injury prevention and injury treatment.

"Rugby is a constantly evolving game. Like all sports, rugby is not risk free, but it is a sport that cares greatly for and prioritises its players particularly when it comes to head injury.

"We are aware that Justin is part of a legal claim against governing bodies in the sport, including the RFU. We have not yet had the detailed claim and will give that careful consideration and respond as appropriate in due course.

Alix Popham is another player who has early onset dementia

"As a sport, rugby has established concussion and injury surveillance, concussion assessment and law changes to ensure proactive management of player welfare.

"We and the Rugby Players Association have made contact with all former players to share the work we have and are doing to help players including the launch last year of an advanced brain health clinic for retired players, external."

The RFU also said it had launched its own concussion and awareness programme in 2013 called Don't be a Headcase, which covers all levels of the sport.

"We continue to work closely with World Rugby, the Rugby Players Association, Premiership Clubs and Premiership Rugby to ensure player welfare remains at the heart of all our decision making."

Wring says that despite all the turmoil in his life since 2008, if he could go back to the playing fields of Barton Hill and do it all again "I would still pick up the ball and play".

"If I knew what I know now, I would still play. But I would manage it all so differently," he said.

"And if that meant I wasn't offered a contract, then so be it, but it would not be for a lack of wanting to play the game of rugby, because it was the love of my life."

Follow BBC West on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to: bristol@bbc.co.uk

- Attribution

- Published31 August 2021

- Attribution

- Published30 August 2017