Henrietta Lacks: Play gives voice to 'mother' of modern medicine

- Published

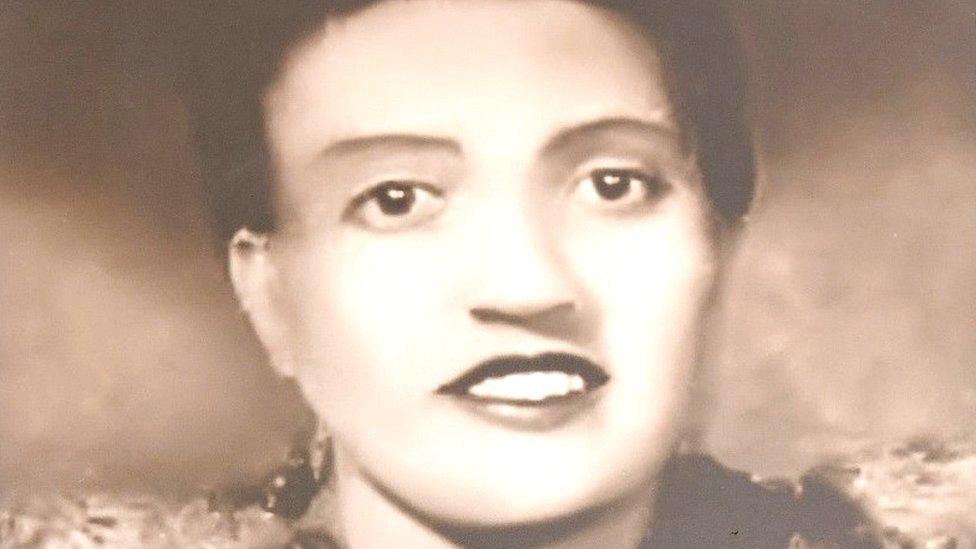

Family Tree was inspired by the legacy of Henrietta Lacks whose cells were taken by doctors without her knowledge

The ability of scientists to treat and prevent many diseases would not be the same without cells taken in the 1950s from a young African-American woman called Henrietta Lacks.

Her immense contribution to science has inspired a play to be performed in Bristol.

Ms Lacks, from Maryland, USA, was diagnosed with cervical cancer in 1951 and, during her treatment, doctors harvested samples of her cells without her consent or knowledge.

They were the first living human cells to multiply outside the human body and have since been used in research that led to the polio vaccine and gene mapping.

These and other advances resulted in Ms Lacks being named the "mother" of modern medicine.

Family Tree is a new drama exploring her astonishing scientific legacy. It opens at Bristol's Tobacco Factory from Tuesday.

"I wanted to write something where we would hear Henrietta's voice. It was about imagining her speaking to us today," explained playwright Mojisola Adebayo.

"Her cells have given rise to the greatest biological findings in history and she's still alive, her cells are still dividing, even as I write… so we all need to take a moment to picture Henrietta Lacks and listen to her remarkable story."

"Henrietta Lacks' life, death, body, cells and story has affected just about every person on the planet since the 1950s. If you have ever taken medication or had a vaccination, a treatment for cancer, IVF, HIV - just about anything really, it has been tested on Henrietta's cells," added Ms Adebayo.

Who was Henrietta Lacks?

In 1951, Henrietta Lacks, a mother of five in Baltimore, was examined by gynaecologists at Johns Hopkins Hospital who discovered a large mass on her cervix.

Samples taken from Henrietta Lacks' cancerous tumour in 1951 produced the HeLa cell line, which has led to crucial medical breakthroughs.

Without informing her or asking for permission, doctors sent a sample of Ms Lacks' tumour to a lab for medical research.

At the time, it was common practice for doctors to harvest samples from their patients, said Johns Hopkins' historians, external.

But Ms Lacks' cells proved to be a medical miracle. While nearly all cell cultures died quickly in the lab, these cells continued to multiply, making them "immortal".

The cell line, called "HeLa" after Ms Lacks' first and last names, has since been sent to research labs around the world.

To this day, the cells endure in labs around the world and were at the forefront of research into the COVID-19 virus.

Speaking to the BBC in 2020 as the pandemic took hold, Ms Lacks' family was delighted to hear her cells were continuing to save lives.

"It just makes me proud because she's not only helping a specific group of people, but she's helping everybody worldwide. She's giving life, with these, I say, 'magical cells'", said Ms Lacks' granddaughter, Jeri Lacks-Whye.

Henrietta Lacks' family were only made aware of her contribution to science in the 1970s.

But while the "HeLa" genome laid the foundations for the multi-billion dollar biotech industry, Ms Lacks' family said it had never shared in any riches generated by the so-called immortal cell line.

Her relatives only learned the cells had not only been extracted, but shipped to laboratories around the world, when a scientist contacted them in 1973 to request a blood sample.

Although they have never received any financial reparation, the family now collaborates with the USA's National Institutes of Health on the HeLa Genome Committee with control over who is able to access the cells' DNA code.

The Henrietta Lacks statue, made by Bristol artist Helen Wilson-Roe, was commissioned by the University of Bristol.

A bronze statue of Ms Lacks, made by Bristol artist Helen Wilson-Roe, was unveiled at Bristol University in 2021 to mark the 70th anniversary of her death.

"In the last year alone, HeLa cells have been used for research into cancer, COVID-19, mitochondrial disease, Parkinson's, HIV and meningitis," said Professor of Biochemistry Harry Mellor, at the time of the unveiling

The play Family Tree also highlights the contribution of others in the name of medical advancement.

"Henrietta was the starting point [for the play] but I am particularly interested in extraction from bodies. It expanded from thinking about extraction from Henrietta to extraction from other black women in terms of the history of gynaecology and research on enslaved African-American women," said Ms Adebayo.

"It's how we acknowledge those people and those hidden histories and bring them from the margins to the centre," she added.

Matthew Xia, artistic director of Actors Touring Company, said: "It's a play which responds to the present moment whilst holding historical malpractice to account."

Ms Lacks died from cancer months after her diagnosis, at just 31. She was buried in an unmarked grave in a racially-segregated hospital in Baltimore.

Family Tree runs from June 13-17 at the Tobacco Factory, Bristol

Follow BBC West on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to: bristol@bbc.co.uk , external

Related topics

- Published22 December 2022

- Published14 December 2022

- Published4 October 2021

- Published9 March 2021

- Published8 August 2013