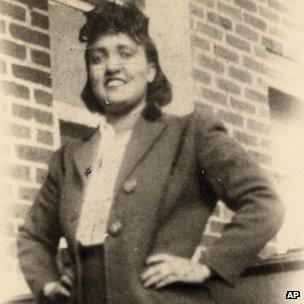

Henrietta Lacks: Family win recognition for immortal cells

- Published

Her story was made famous by 2010 best-seller The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

The family of a US woman whose cells revolutionised medical research have been granted a say over how they are used, six decades after her death.

Henrietta Lacks, a poor black woman from Maryland, had cells removed from her by doctors when she was being treated for terminal cancer in 1951.

Researchers found they were the first human cells that could be grown indefinitely in a laboratory.

The historic breakthrough paved the way for countless medical treatments.

The story of how an African-American tobacco farmer unwittingly transformed biomedicine was made famous by a 2010 best-seller, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.

'Left in the dark'

She was 31 years old when she died of cervical cancer at Baltimore's Johns Hopkins Hospital. Her tumour cells were removed without her consent, as was typical at the time.

Lacks' extracted cells did something never seen before - they could be kept alive and grow

The genetic material later yielded key developments in such areas as vaccines, cancer and fertility treatment, spawning nearly 75,000 studies.

But while the "HeLa" genome laid the foundations for the multi-billion dollar biotech industry, Lacks' family have never shared in any of the riches generated by the so-called immortal cell line.

Her relatives only learned the cells had not only been extracted, but shipped to laboratories around the world, when a scientist contacted them in 1973 to request a blood sample.

The family will still not be paid any money under the agreement reached on Wednesday with the National Institutes of Health, external, the US government agency which oversees medical research.

But they will be granted some control over scientists' access to the cells' DNA code, and receive acknowledgement in the resulting studies.

The agreement came about after the relatives raised privacy concerns when German researchers published Lacks' DNA code in March.

Rebecca Skloot, author of the acclaimed book about Lacks, took part in the negotiations leading to the agreement and said the family had never asked for money.

Jeri Lacks Whye, a granddaughter who lives in Baltimore, said the relatives had always been "left in the dark" about research stemming from HeLa cells.

"We are excited to be part of the important HeLa science to come," she told the Associated Press news agency.