Cambridge Digital Library looks to turn traditional library 'inside out'

- Published

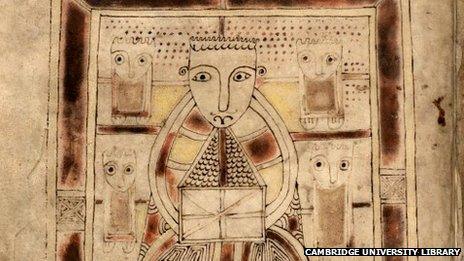

The oldest surviving Scottish manuscript - the Book of Deer - is one of thousands of pieces of text that have been put online

It was proclaimed as a "digital library for the world", with scholars, students and bookworms being able to access some of the rarest and most significant pieces of literature ever written.

A year on, thousands of books and manuscripts held by the University of Cambridge have been uploaded to the Cambridge Digital Library, and many more are expected to be digitised in the next couple of years.

But it is a mammoth project - how do you put 600-year's worth of the written word on the internet?

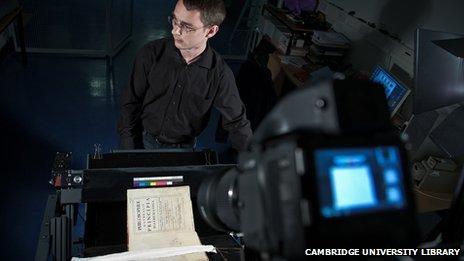

The answer is with a team of about 30 experts, five 80-megapixel cameras, several high-end scanners and a lot of dedication.

Grant Young, director of the Cambridge Digital Library project, said it was about turning the traditional library "inside out" and finding a way of sharing the university's often hidden possessions with people across the globe.

"This is one of the great research libraries that over the past 600 years has been amassing amazing collections from all parts of the world and all cultures, so we really felt that we should be making that more accessible," he said.

Pages of history

"We want to share these treasures with the world. We want to be surprised at what people do with it and the discoveries that are made from it.

"We want to advance scholarship, research and teaching and we want this to be used and enjoyed."

The Cambridge Digital Library began after a £1.5m donation from the Polonsky Foundation charity, which supports international developments in higher education and research.

It now holds about 3,700 items online, with internet users being able to browse through 35,000 pages of history for free.

Isaac Newton's papers including his Principia Mathematica have been put online

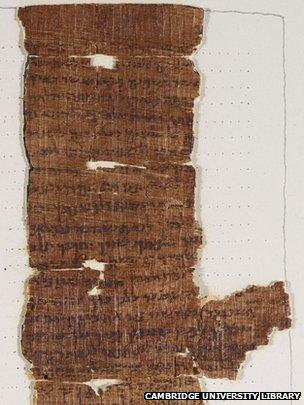

So far people have been allowed to view some of the rarest pieces of scientific literature, including the notebooks of Sir Isaac Newton, and allowed access to early religious texts such as a 2,000-year-old copy of the 10 Commandments.

Many items have never been on public display and their rarity seems to have captured people's interest.

The university said the project's website had received tens of millions of hits in just 12 months, with visitors viewing the content "from every part of the world".

A further 100,000 digitised images are expected to be uploaded next year. But despite the project taking potentially years to complete, Mr Young believes it will "undoubtedly" be worth the effort.

"We've made a good start but there's so much more that we want to do.

"We have had a lot of scholars that have been very excited by this and they've been able to see things that they have only seen as transcriptions or bad microfilms. Some of these things - particularly the Newton papers - are works that they've spent their careers studying, so that's exciting.

"We're also talking to other museums and libraries that have collections related to ours and are talking about how to enable people to discover content that is split across collections.

'Protected from destruction'

"Over the next year we're going to be developing means of people annotating the content or easily sharing it via social media.

The Nash Papyrus is one of thousands of historical texts that have been placed online

"If they want to have a go at adding a transcription or translation for other languages we will be turning that on as well.

"What people see at the moment is only the tip of the iceberg."

But the project will cost millions of pounds to achieve.

The charity funder Dr Leonard Polonsky says people from all walks of life will benefit.

"Great public collections shouldn't be limited to a small audience of academics. That's in no-one's interest.

"And bigger audiences for these collections will result in greater interest in academic work.

"My desire is to get online as much of the world's inheritance of knowledge and literary expression as possible.

"At the same time, these treasures will be protected from destruction. Should there be a fire, the physical items may disappear, but their digitised facsimiles will be available forever."

- Published13 December 2012

- Published12 December 2011

- Published19 September 2011

- Published4 June 2010