Cambridgeshire plesiosaur 'sea monster' could be 'new species'

- Published

Plesiosaurs were sea creatures that lived at the time of the dinosaurs

A Jurassic "sea monster" found in Cambridgeshire could prove to be a new species of plesiosaur, scientists said.

Oxford archaeologists discovered the 165 million-year-old reptile bones at Must Farm quarry near Whittlesey.

Dr Carl Harrington and his team dug up more than 600 pieces of bone as well as the skull, still preserved in clay.

"Eve", described as "a fantastic fossil", has anatomical features only before seen in plesiosaurs half her size, a palaeontologist said.

Plesiosaurs were sea creatures that lived at the time of the dinosaurs.

Hundreds of bones were recovered from the Must Farm quarry site

Eve's "snout" was the first thing Dr Harrington noticed as he was digging around in the wet clay.

"It was one of those absolute 'wow' moments. I was the first human to come face-to-face with this reptile," he said.

In all, the team from Oxford Clay Working Group dug up hundreds of pieces of fossilised bone and spent more than 400 hours cleaning and repairing the remains.

"I'd never seen so much bone in one spot in a quarry," Dr Harrington added.

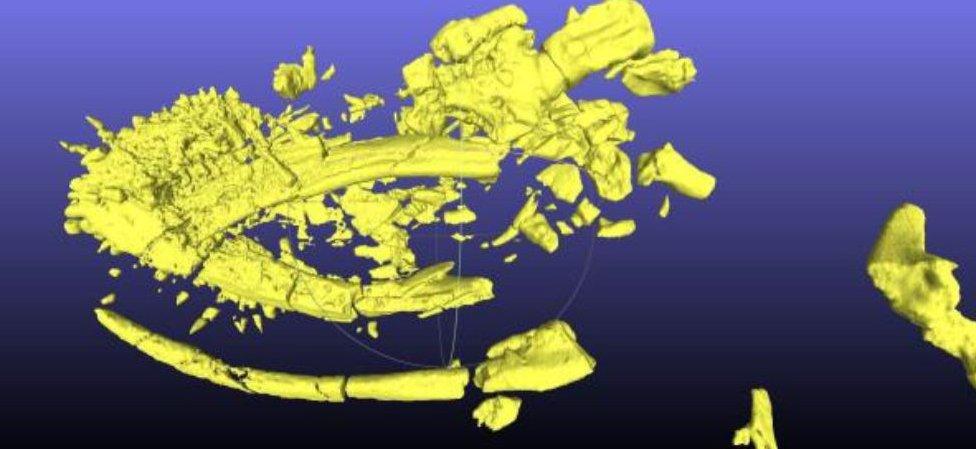

The plesiosaur's skull is still encased in clay and has been scanned to enable the bones to be retrieved without damaging them

The vertebrae and other bones are being studied by palaeontologists

Almost all of the plesiosaur's bones have been found, although the hind flippers and parts of the fore-flippers are still missing.

The site of Eve's final resting place - owned by building product manufacturing company Forterra - has given up a number of important finds over the years.

Cambridge archaeologists are currently excavating the remains of a Bronze Age settlement described as "Britain's Pompeii" because it is so well-preserved.

However, Eve is much older and palaeontologists have reason to think she is a "previously unknown species of plesiosaur".

Plesiosaurs (Plesiosauroidea)

The sea reptiles varied in length from about 6.5ft (2m) to 50ft (15m)

They had extremely long necks with up to 76 vertebrae - mammals such as humans and giraffes have just seven

Plesiosaurs fed on other marine animals such as fish and shellfish

Scientists estimate the Cambridgeshire plesiosaur to have been about 6m long, weighing about 660lb (300kg)

The creatures could reach speeds of about 5mph (8.2km/h) in the water

They are often depicted with their necks bent, but experts say the plesiosaur neck was not in fact that flexible

Plesiosaurs became extinct 66 million years ago

Source: Oxford University palaeontologist Dr Roger Benson/BBC Nature

The skeleton is currently being studied by experts at Oxford University's Museum of Natural History.

Palaeontologist Dr Roger Benson said although Eve has a long neck, which is not uncommon, she also has "some anatomical features only seen in Picrocleidus, a plesiosaur about half the size of this new skeleton".

The Must Farm specimen had an 8ft (2.5m)-long neck, a barrel-shaped body, four flippers and a short tail.

Scientists are currently working to remove the skull from inside a block of clay.

Scientists say some of the Cambridgeshire plesiosaur's anatomical features have only been found in much smaller specimens

It has been CT-scanned by the Royal Veterinary College to enable them to accurately locate the bones without damaging them.

Eve was donated by Cambridgeshire landowners Forterra to the Oxford museum, who said they were "very excited" to have the new "sea monster" in their collection.

- Published12 January 2016

- Published12 January 2016

- Published15 April 2015

- Published12 August 2011