Female scientist's IVF contribution was 'unrecognised'

- Published

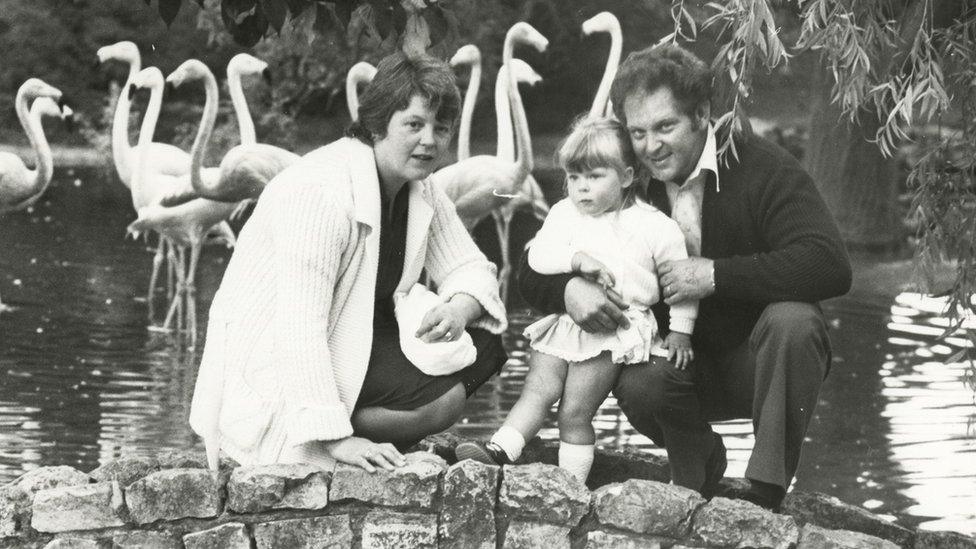

Jean Purdy and Robert Edwards worked together on the development of IVF

A female scientist's contribution to the discovery of IVF went "unrecognised", her colleague believed.

Sir Robert Edwards and Patrick Steptoe are known as the pioneers of in vitro fertilisation, which led to the world's first test tube baby, born in 1978.

But newly released letters from Sir Robert show he fought for Jean Purdy's equal contribution to be publicised.

In a letter to Oldham Health Authority, he said the embryologist had "contributed as much to the project".

IVF pioneers Sir Robert Edwards (L) and Patrick Steptoe (R) pose with Louise Brown and the midwife following her birth

The authority had been about to unveil an official plaque at Kershaw's Cottage Hospital near Oldham to mark the birth of Louise Brown, the world's first IVF baby.

Sir Robert tried to get Ms Purdy's name included alongside his and Mr Steptoe's at plaques at all the hospitals involved in the project but was unsuccessful.

Other letters show his repeated attempts at convincing the National Health Service to support IVF work.

The documents have been put on public display at Cambridge University's Churchill Archives Centre.

John and Lesley Brown received hundreds of cards and letters after the birth of Louise

Ms Purdy joined Sir Robert in 1968 and worked closely with him, travelling to California in 1969 to carry out research.

She was involved in trials and helped to set up Bourn Hall in Cambridgeshire in 1980 as the world's first IVF clinic.

It has been estimated that six million babies all over the world have since been born thanks to the procedure.

A Cambridge University spokeswoman said: "Her work as a woman in science has gone largely unrecognised when compared to Edwards and Steptoe.

"The papers will be invaluable for researchers in the history of science, but also in the history of ethics, social implications of medical developments, and political and media history."

Sir Robert was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2010, and was knighted in 2011.

Ms Purdy died in 1985 and Mr Steptoe in 1988.

- Published25 July 2018

- Published23 July 2015