Ancient gold Kazakh treasures shed light on Saka people

- Published

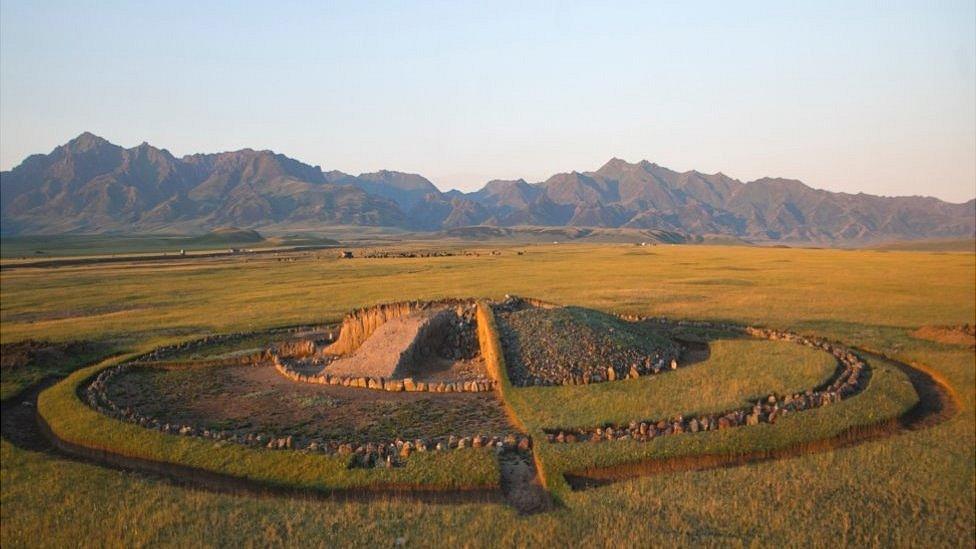

The exhibition includes finds from three burial complexes in eastern Kazakhstan - Berel, Shilikti and Eleke Sazy - and from a settlement called Akbauyr

Astounding gold artefacts belonging to a prehistoric nomadic warrior horse people are going on display in the UK for the first time.

Many of the treasures were recently discovered in Saka burial mounds in East Kazakhstan - part of an ancient culture which is largely unknown outside the central Asian country.

They left no written accounts of their beliefs and culture, but the latest archaeological techniques are starting to reveal their secrets.

BBC News has been finding out more about the artefacts at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, to discover who the Saka really were.

The teenage archer found at the Eleke Sazy burial mounds, wearing clothes studded with gold, close to the looted grave of his sister

A reconstruction of the burial of a high-rank teenage archer, discovered in a burial mound in 2018, has been included in the exhibition.

The boy, who was aged about 16, was interred with tenderness and care, surrounded by gold artefacts, wearing shoes sewn with thousands of tiny gold beads and with a dagger which was deliberately broken before burial.

Dr Rebecca Roberts, curator of the exhibition, said he was "buried like a warrior, yet was just a gangly youth on the verge of manhood".

His burial was typical of the Saka, who left behind exquisite gold artefacts created by highly skilled craftspeople in their burial mounds, which were ambitious technological constructions.

Who were the Saka?

The cult of the deer was important to the Saka, who had many items like this gold stag inlaid with turquoise

The Saka culture dominated the Eurasian steppe, from the Black Sea to Siberia, from about 900BC to 200BC. Yet, until the 18th Century when an explosion of looting of the burial mounds led to the discovery of hundreds of gold artefacts, they were only known about through the writings of the ancient Greeks and Persians - as fearsome warriors, but also as "barbarians".

They were the "earliest expression" of ancient tribes of nomadic warriors, later known as the Scythians, external.

Dr Roberts said: "We call them the Saka collectively, but we don't even know how individual groups referred to themselves."

There is a possible clue among the writings of the ancient Greek author Herodotus (about 484BC to 420BC).

He described a traveller who reached the farthest reach of the steppe and wrote about encountering a one-eyed people - and beyond their lands was the part bird, part mammal griffin which "guarded the gold".

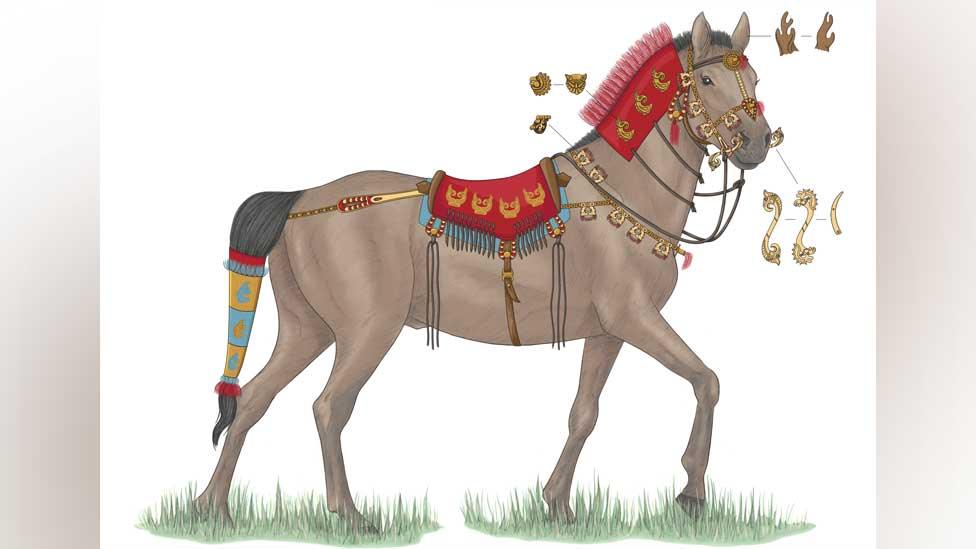

They had an intense relationship with horses - their warriors often took their favourite horses with them to the grave, elaborately decorated with golden outfits

Dr Roberts said: "One question historians ponder is if the Saka of East Kazakhstan called themselves griffins?

"After all, the fantastical creature combines mammal and bird and is not dissimilar to creatures found in Saka works of art."

Persian sources used the terms Scythian and Saka interchangeably - yet also wrote about their differences.

"They said the Saka had pointed hats and consumed haoma - a stimulant drink made from some sort of plant," said Dr Roberts.

There are three key factors used to identify Saka culture - they were highly mobile and sophisticated equestrians, they used a short composite bow designed to be fired from horseback and they created stylised animal art.

But the only way to find out what they thought about themselves is to analyse what they left behind.

The sheer amount of gold artefacts buried with the Saka was also a massive proclamation of social status, said Dr Roberts

This heritage is under threat from looting and degradation due to climate change.

Five years ago, the East Kazakhstan Region launched a large-scale archaeological research programme and dozens of new archaeological sites have been discovered and studied.

In addition, Kazakhstani researchers have commissioned the latest in archaeological science.

This includes a method called proteomics, which can "extract traces of protein molecules from a broad range of objects," said Gleb Zilberstein, from Israeli company Spectrophon.

This dagger sheath with turquoise and lapis lazuli inlays shows how highly skilled their craftspeople were

Teeth, bones, biological materials and recently unearthed gold artefacts were analysed by Mr Zilberstein and Italian professor Pier Giorgio Righetti.

They have discovered the sort of herbs burned in Saka rituals, the unique microbiome (combined genetic material) they used to ferment milk, traces of the plants and the animals they ate - and that they used a mix of beeswax and pureed calcite (a rock-forming mineral) to make teeth fillings.

They were particularly asked to check for smoke traces on lamps believed to be used in rituals.

Here they found traces of sweet wormwood, a plant common in Kazakhstan which has long been used to treat fevers and is the main ingredient in absinthe.

The Saka often depicted stylised animals with twisted legs, such as these deer plaques found at Eleke Sazy

Traces of antiseptic ferns and pain-relieving cannabis found at the burial of a woman in an elaborate gold headdress, who was probably a priestess or herbalist, shows the Saka's "very sophisticated knowledge of the properties of the wild plants around them," said Dr Roberts.

DNA analysis of the bones "reveals they were not a united nation, but small families, different from one another," according to Mr Zilberstein.

"It was a region where people were intensively mixing from migration - after all Alexander the Great (356BC to 323BC) visited."

Danial Akhmetov, governor of the East Kazakhstan Region, said the "exceptional state of preservation" of the teenage burial mound will bring new opportunities for scientists to study the "religion, world view and funeral rites of the early Saka people".

And as archaeological science continues to innovate, it is likely that more of the Saka's secrets will be revealed.

Gold dove headdress plaques will be included in the exhibition

Gold of The Great Steppe will open at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, on 28 September and run until 30 January.

Find BBC News: East of England on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and Twitter, external. If you have a story suggestion email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk, external

Related topics

- Published9 August 2021

- Published8 August 2021

- Published30 May 2021

- Published6 October 2019

- Published16 August 2019

- Published23 July 2019