Cambridge University: 'When to be poor, pretty and petulant was a crime'

- Published

Daisy Hopkins was arrested by Cambridge University's Bulldogs in 1891 and her case attracted world-wide attention

A murky tale of misogyny and class prejudice has been unearthed from the ledgers of Cambridge University's prison.

Throughout the 19th Century, it locked up women it suspected of soliciting students or dons in the Spinning House.

No evidence was needed, no fair trial was offered and sentencing was arbitrary.

For the women caught up in in this system, "being poor, pretty and petulant seemed the biggest crime", according to historian Caroline Biggs.

So, how did a teenager called Daisy Hopkins help bring about its demise?

She is one of four women whose stories were traced by Ms Biggs, whose book on The Spinning House is out on Friday, external.

"I'd known about the story for a while and was intrigued about the legend of a prostitute that brought about the demolition of the prison," the Museum of Cambridge trustee said.

"When I started a creative writing MA, I looked into it and discovered so much more than I expected to find."

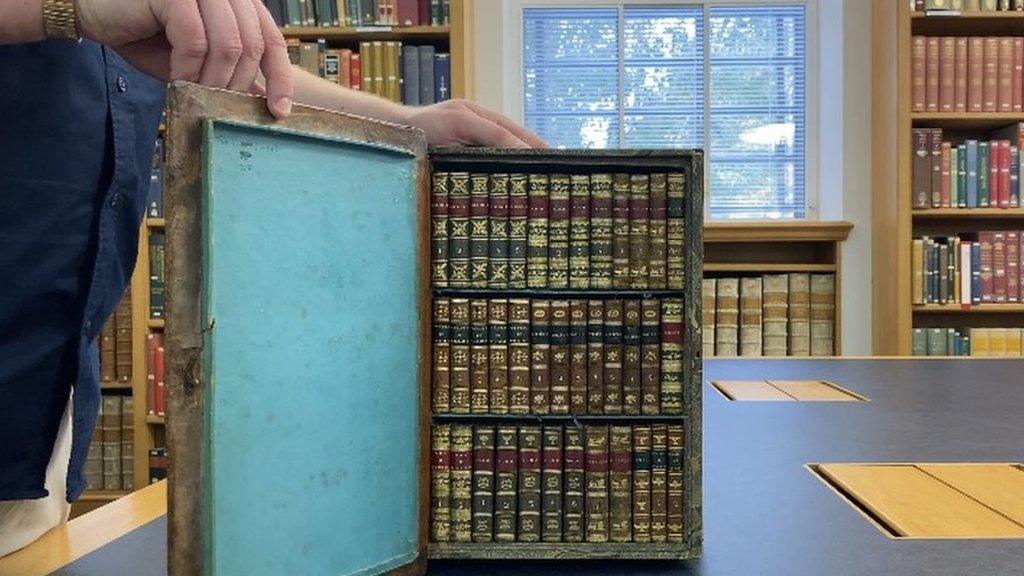

Caroline Biggs unearthed the stories of the working class women jailed by Cambridge University from its prison committal books

Daisy Hopkin's case of wrongful imprisonment in 1891 made national and international headlines, but so did those of Elizabeth Howe, Emma Kemp and Jane Elsden in the preceding half century.

"Each of them caused the university enough embarrassment to make small changes to how they ran the prison," said Ms Biggs.

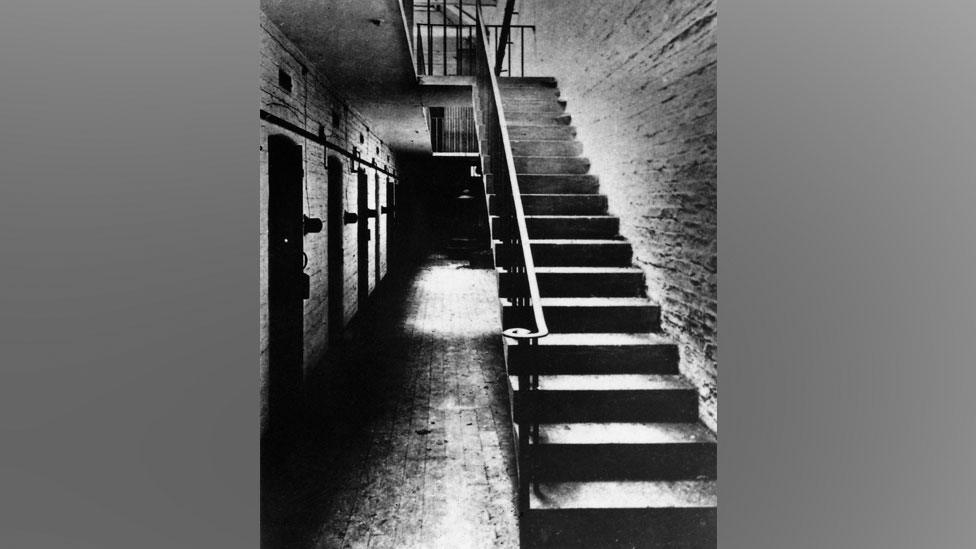

In December 1846, a coroner's inquest found Elizabeth Howe, 19, died from "being put to a damp bed in the Spinning House".

Her death caused national outrage and forced the university to improve the prison's conditions, having ignored similar calls by prison inspectors for years.

Jailing women in the Spinning House also ruined their reputation making it hard for them to find employment.

Emma Kemp, 24, had the courage to take to court her arresting proctor over a wrongful arrest in 1860. Proctors were university officials who patrolled the streets, responsible for maintaining discipline.

She was cleared, but the dressmaker and her mother both lost trades they had carefully built up over years.

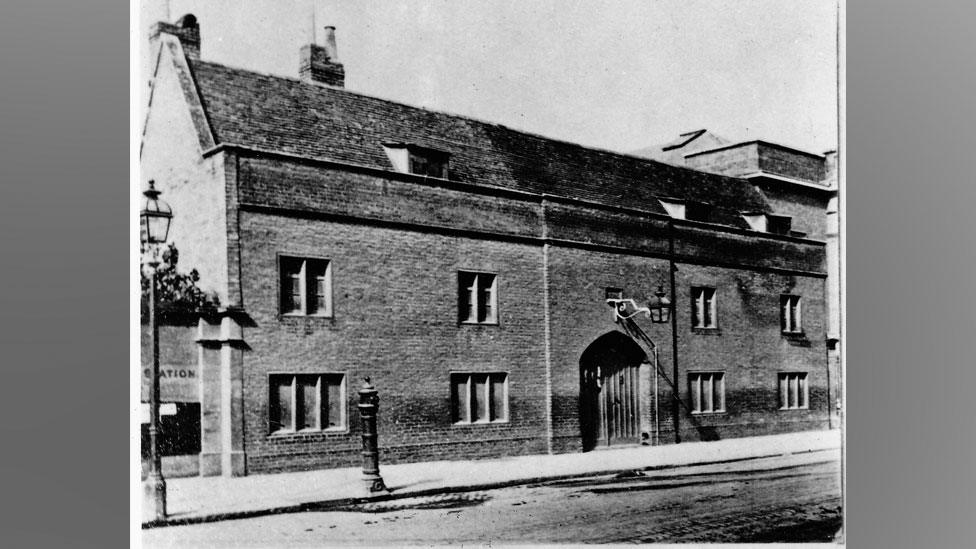

The women were jailed in the Spinning House, which was criticised by prison inspectors for its "disgraceful state" throughout the 1830s and 1840s

The origins of the university's control over the right of women to walk in Cambridge after dark go back to an Elizabethan charter.

This allowed its senior members to arrest and imprison any woman "suspected" of prostitution.

It was introduced to prevent the town's mayors from releasing women jailed by university.

Then in 1825, an Act of Parliament gave the university a private police force of special constables, nicknamed the Bulldogs by townspeople, to accompany the proctors.

Ms Biggs said: "Bulldogs took pride in sniffing out every morsel of tittle tattle about the young women living in Cambridge."

Those arrested were taken to the university's vice-chancellor for sentencing.

Conditions improved after the death of Elizabeth Howe caused outrage locally and nationally

But they were only meant to target women found "in the company" of a member of the university.

So when Jane Elsden, 17, was dragged to the Spinning House in 1891, despite being alone, the subsequent furore exposed the lack of due process faced by all the women.

Ms Biggs has examined more than 6,000 arrests of women "suspected of evil" by university officials during the 19th Century.

None had a fair trial, no law was broken, no evidence of wrongdoing was recorded and sentencing by the vice-chancellor was arbitrary, usually dependent on the woman having "come quietly", she said.

Most were teenagers and more than half single offenders.

"I'm not naive enough to think some weren't prostitutes, but the point is we don't know as there was no evidence," she said.

The university did slowly evolve during the 19th Century, from an all-male institution to one with women's colleges

The main goal was to remove women and temptation from the streets.

Ms Biggs said: "Parents were terrified their precious sons might fall prey to immoral behaviour. It was argued that it was the university's duty to protect men destined for greatness.

"Of course, dons and undergraduates kept mistresses... the double standard was alive and kicking."

A few months after Jane Elsden's case, Daisy Hopkins, 17, was jailed despite a man admitting to soliciting her.

A case of habeaus corpus was brought - so a judge could decide whether she was being kept in prison legally or not - in a landmark case still referred to today, external, securing her release.

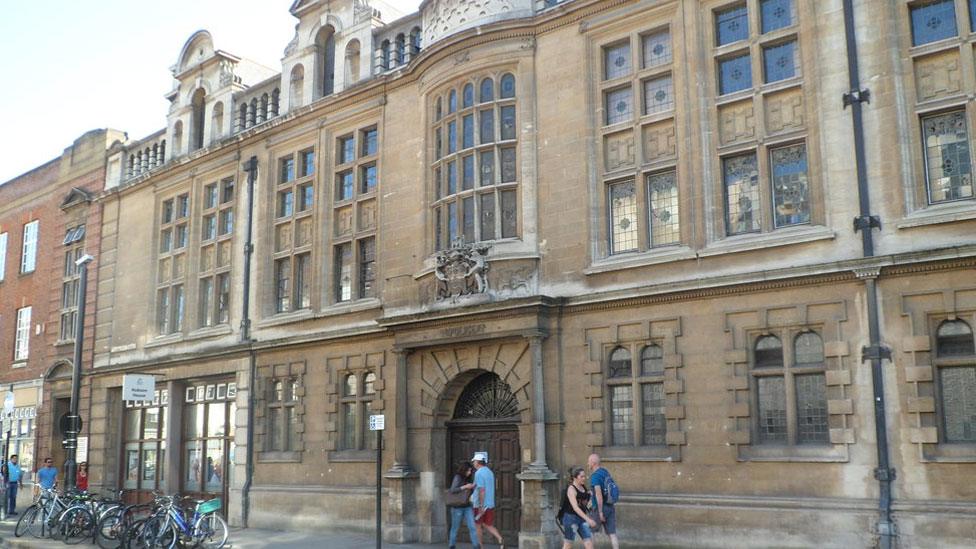

The 17th Century Spinning House was demolished and a purpose-built police station opened in its place in 1901

The university had been slowly evolving during the 19th Century, with male academics allowed to marry from the 1880s, and women's colleges opening up.

In 1894, an Act of Parliament revoked the university's Elizabethan charter, terminating the vice chancellor's right to arrest and imprison women who were suspected of prostitution.

Ms Biggs said: "It is a fact that many were innocent, but their association with the Spinning House ruined them regardless."

The building was demolished and replaced with a police station in 1901.

Follow East of England news on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and X, external. Got a story? Email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk , externalor WhatsApp 0800 169 1830

Related topics

- Published28 February 2024

- Published20 September 2023

- Published4 October 2022

- Published27 June 2021