Cambridge University study solves Anglo-Saxon coin mystery

- Published

Experts speculated the silver could have come from France, or from melted down sources, but had no "hard evidence" until now, said Rory Naismith

The origins of the silver used in 7th Century Anglo-Saxon pennies have been revealed after analysis of 49 coins.

Anglo-Saxon England experienced a rapid surge in the use of silver coins between 660 and 750 AD, but historians had no "hard evidence" of its source.

They now know Byzantine bullion and a French silver mine were behind the increase, said the joint Cambridge and Oxford university study.

Prof Rory Naismith said it was "such an exciting discovery".

"I proposed Byzantine origins a decade ago but couldn't prove it," the Cambridge University professor of Early Medieval English History said.

"Now we have the first archaeometric confirmation that Byzantine silver was the dominant source behind the great 7th Century surge in minting and trade around the North Sea."

About 7,000 silver pennies have been recorded from this time, compared to about the same number for the entire Anglo-Saxon period (5th Century to 1066).

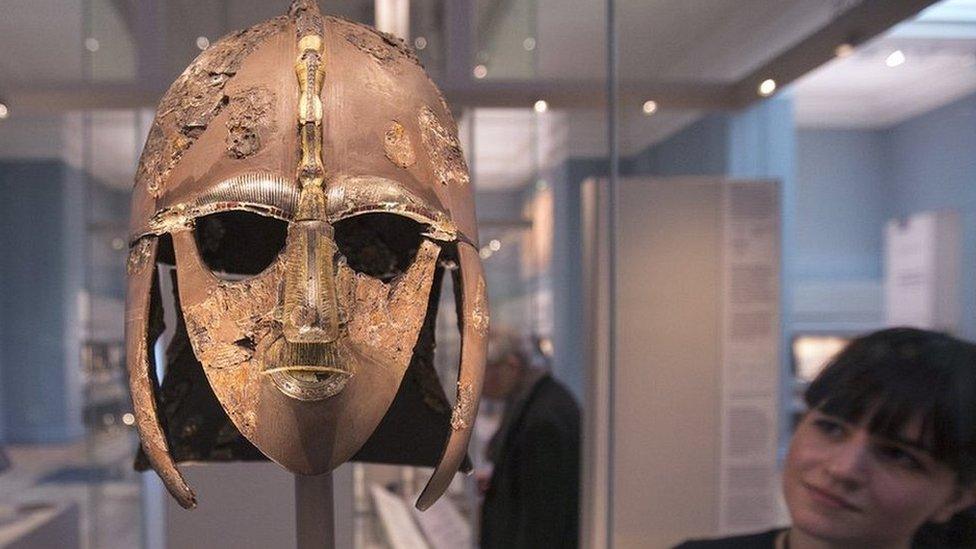

A study of 49 silver coins from the Fitzwilliam Museum helped establish the metal's origins

Prof Naismith and his colleagues examined coins held by the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. They were minted in England, the Netherlands, Belgium and northern France.

The coins were first given trace element analysis and then analysed using a technique pioneered by the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, which also participated in the research.

A "portable laser ablation" was used, in which microscopic samples were collected onto Teflon filters for lead isotope analysis.

This established 29 coins from 660 to 750 AD were made from 3rd to 7th Century silver from the Byzantine Empire in the eastern Mediterranean, external.

The researchers, who have published their findings in Antiquity, external, believe the metal entered Western Europe decades before and was melted down in the late 7th Century "when a king or lord urgently needed lots of cash".

The study's lead author, Oxford University's Dr Jane Kershaw, said: "This was quantitative easing, elites were liquidating resources and pouring more and more money into circulation."

Coins from this period "are among the first signs of a resurgence in the northern European economy since the end of the Roman Empire", said Jane Kershaw

The study's second major finding was that the silver used to mint the 750 to 820 AD coins was very different. It was mined in Melle in Francia, part of modern day western France.

It argues the emperor Charlemagne (768-814 AD), external drove this very sudden and widespread surge in Melle silver.

The authors said this also gives a new context to the emperor's "delicate diplomatic relations" with Offa of Mercia (757-796 AD, external) in England.

Prof Naismith has no doubt that people in England would have been very aware that their silver was coming from Francia and that they depended on it.

"[Offa] remained one of Europe's most powerful figures who was outside Charlemagne's control. He certainly didn't have as much silver. So they maintained a pretence of equality," he said.

"Our findings add to a dynamic that England and France have had for a very long time."

Follow East of England news on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and X, external. Got a story? Email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk, external or WhatsApp 0800 169 1830

Related topics

- Published8 March 2024

- Published3 December 2023

- Published29 July 2023

- Published27 April 2023

- Published17 January 2021