Coventry IRA bombing: The 'forgotten' attack on a British city

- Published

The bomb went off on Broadgate - one of Coventry's main shopping streets

On 25 August 1939, five people died and 70 were injured when an IRA bomb exploded in Coventry city centre. Yet 75 years after the explosion, the devastating attack has been all but forgotten. BBC News Online asks why.

It is easy to picture Elsie Ansell weaving her way through the Coventry crowds, her footsteps buoyant, her future full of promise.

Elsie, 21, a shop assistant at Millets, was due to be married in a fortnight's time to Harry Davies, a local man.

Friday was market day in Coventry and Broadgate, the main shopping street, thronged with shoppers and workers.

Elsie paused, just for a second, to gaze into a jewellery shop window.

Rex Gentle with his fiancee May - the couple were due to be married when Rex died in the blast

In that second, the hands of an alarm clock, placed in the carrier basket of a bicycle which was resting on the kerb behind Elsie, moved to 14:32 BST and a 5lb (2.3kg) bomb exploded, shattering shop windows and lives.

"For some time, Broadgate resembled a miniature battlefield," the Midland Telegraph reported.

Elsie was killed instantly. The young girl, whose life had seemed destined for such happiness, was identifiable only by her engagement ring.

She was later buried in the church where she was due to be a bride - one of five victims of the explosion.

Marie Jones said her father Jack "knew" his brother Rex had died

"He was just in the wrong place at the wrong time," said Marie Jones, from Andover, the niece of one of the other victims, Rex Gentle.

Rex, 30, was an identical twin from Newtown in Wales.

Like Elsie, Rex was engaged. He planned to marry a girl called May from his hometown.

He was doing holiday relief work at W.H. Smith and had only been in Coventry for a fortnight.

"He loved a laugh and a joke and was known for his willingness to help other people," said Mrs Jones.

'Deal with the devil'

Police investigations revealed the bomb had been planted by the IRA as part of what is now a largely-forgotten campaign of attacks on English cities known as the S Plan.

Dr David O'Donoghue who has written a book - The Devil's Deal - about the campaign said: "The S stood for sabotage. The campaign started in 1939 and petered out in March 1940.

"The official objective was to force a British withdrawal from Northern Ireland."

Broadgate, the scene of the bomb, resembled a "miniature battlefield", according to the newspapers

However, Dr O'Donoghue believes the real motivation was to put on a "public display" to Nazi Germany about the IRA's capabilities.

The Coventry bombing took place just nine days before the outbreak of World War Two and the IRA attacks on cities including Birmingham, Manchester, Oxford, Liverpool and London, continued until March 1940.

"This predated the discovery of concentration camps and other Nazi horrors," Dr O'Donoghue said. "The IRA would have done a deal with the devil to get a united Ireland."

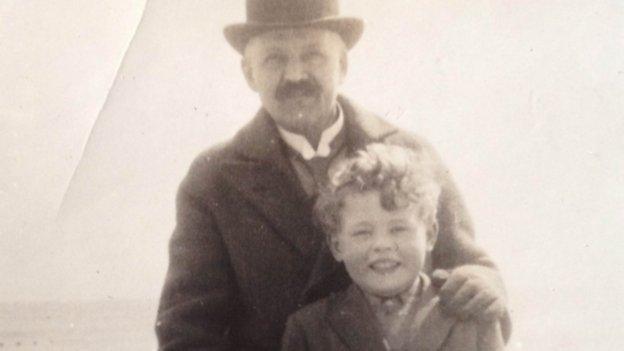

John Arnott, pictured here with his father, was the youngest victim of the bombing

Five people died in the explosion:

Elsie Ansell, 21, who was walking back from her lunch break.

John Arnott, 15, was the youngest victim. He had worked for W.H. Smith since leaving school. Newspaper reports described him as, "a curly-headed lad who wore glasses and must have served thousands of Coventry people with their papers and magazines". "He was full of life and well thought of by everyone that met him," said Jane Bant, his niece.

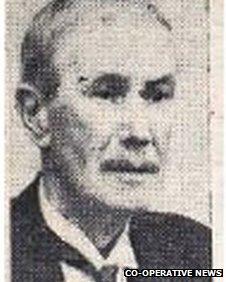

Victim James Clay - the "Peter Pan of the Midlands"

Rex Gentle, 30, was an identical twin from Newtown in Wales.

James Clay, 82, was a widower and grandfather. Newspapers said he was "well-known to an older generation of Coventry people" and "possessed the physical and mental energy of a man 20 years younger". A former printer, Mr Clay is described as a "deep reader, a great raconteur and a lover of Coventry, where he was born". He was a former president of the Coventry and District Co-Operative Society who described him as the "Peter Pan of the Midlands". He had been having lunch with a friend at a nearby cafe but had left earlier than usual, saying he felt unwell. Newspaper reports said: "It was the first time in six years Mr Clay [and his friend] had not left the cafe together."

Gwilym Rowlands, 50, known as "Bill", was a road sweeper who was working on the pavement outside the shop where the bomb exploded. He was identified a few hours later in the mortuary by his wife, Mary Ann.

The bomb was placed in the basket of a bicycle which was left in the city centre

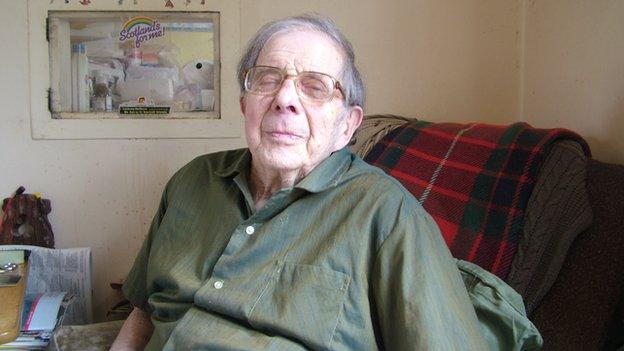

Ted Cross, now 92, was the first ambulance driver on the scene.

"The glass had been sucked out of all the windows and there were a great many casualties," he said.

"The first gentleman I reached had terrible stomach injuries. I think the hub of the bike had blown into him. We took him to hospital but unfortunately he died shortly afterwards."

Ted Cross, now 92, was the first ambulance driver on the scene and can still remember the carnage

Passer-by Robert Kinsella was thrown to the ground in the explosion. "I could see there had been terrible damage done," he said.

"There were a lot of people lying about on the ground. The first person I went to was, I believe, old James Clay, whom I picked up. I could see from his injuries he was almost dead."

About 70 people were injured - some of them seriously.

Sheila Howe said her schoolfriend Muriel Timms was injured in the attack

Sheila Howe's friend from school Muriel Timms, 14, had an operation to remove a piece of steel implanted in her leg.

"She never walked again without a limp," she said. "It was an awful thing for her.

"She died when she was in her early 80s but the experience cast a dark shadow over her life."

The bombers

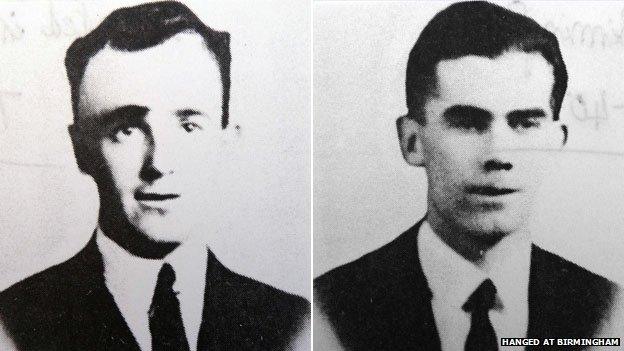

James McCormick and Peter Barnes were hanged for their role in the bombing - although they did not plant the device. McCormick claimed his orders were "not to endanger life"

The man who claimed to have planted the bomb - Joby O'Sullivan, from Cork - was never caught.

Mike Burns, an Irish journalist who interviewed O'Sullivan in 1969, said he had told him the fact the bomb was left on a busy shopping street was "a total accident".

"The intention was to bomb the police station but the bicycle wheels kept getting stuck in the tram tracks so he abandoned it and took off," he said.

"He said he wasn't caught because the cops were expecting him to head straight for the ferry at Holyhead. He took the train to London, dumped his clothes and hung around there for a few days until everything died down."

The bomber, Joby O'Sullivan, claimed he had unintentionally abandoned the bike in the city centre

Instead two other men, Peter Barnes and James McCormick - under the name James Richards - both from County Offaly, were convicted for the bombing and sentenced to death.

McCormick had bought the bike from Halfords and stored the explosives at a house on Clara Street where he lodged.

Barnes brought the explosives to Coventry by train.

During his trial in Birmingham, McCormick insisted his orders were "not to endanger life".

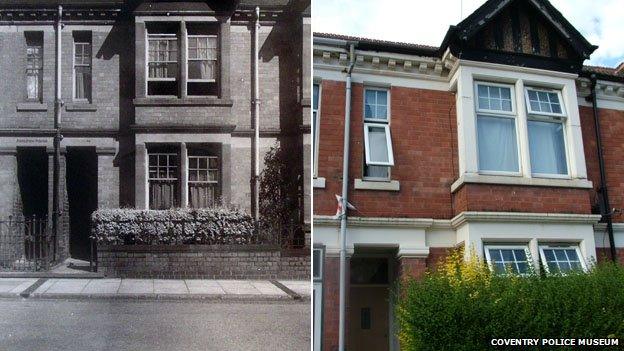

The house on Clara Street, Coventry, where the bomb was made, in 1939 and today

According to criminologist Steve Fielding, whose book Hanged at Birmingham covers the case, the two men were treated as martyrs in Ireland following their executions.

"Their bodies were exhumed and reburied in Ireland," he said.

The bombing formed one of dozens of IRA attacks on English cities between 1939 and 1940

Today the victims - like Rex Gentle - are remembered only by their families and the attack is all but forgotten

Initially, Coventry's considerable Irish community found itself under siege.

"Widespread feeling against Irishmen in Coventry - the vast majority of them entirely innocent of any sympathy with the IRA - has been aroused," the Midland Daily Telegraph reported.

"Such is the feeling Friday's tragic incident has kindled that many Irishmen in lodgings were faced with requests they should obtain accommodation elsewhere."

There were also threats of strike action if factory owners did not consent to an immediate withdrawal of Irish labour.

Even Coventry's chief constable had to issue a denial he was Irish. "I am a perfectly good Somerset man," he said.

Marie Jones (left) whose family continued to meet with the Arnotts following the deaths of Rex Gentle and John Arnott, would like to see a memorial in Coventry

But within days the attack had disappeared from the front pages of Coventry newspapers, replaced with the ominous rise of Hitler and by 3 September Britain was at war.

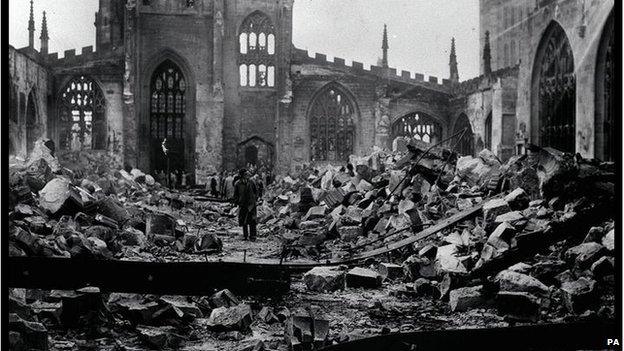

In 1940 much of Coventry's centre was destroyed by the ravages of the Blitz. Even the site of the IRA explosion became unrecognisable, as many of Broadgate's buildings were destroyed.

Jane Bant, niece of victim John Arnott, would also like to see a memorial

Today it is even difficult to work out where the bomb went off and there is no memorial to the victims.

Historian Simon Shaw, who has meticulously studied the attack, said many people do not realise there was a pre-World War Two IRA campaign.

"I get the impression a memorial may previously have been considered contentious but with the progress that has been made in Northern Ireland, I'm sure that wouldn't apply today," he said.

Since World War Two Broadgate has changed beyond recognition and the location of the bomb is difficult to establish precisely

The victims are only remembered by their families.

Marie Jones, daughter of victim Rex Gentle's twin brother, said the story of the Coventry bombings is "something she has grown up with".

"It brings tears to my eyes and I never knew him," she said.

"But nobody in Coventry remembers the attack now. I would just like to see their names somewhere in the city."

"It's one of the worst atrocities there has ever been in Coventry and yet nobody remembers it," added Jane Bant, niece of John Arnott, the teenager who died in the attack. "I think there should be a memorial."

- Published14 November 2013

- Published28 March 2011