I've learned to love the girl I was - author of Poor

- Published

Dr Katriona O'Sullivan dedicates her book, "To me, aged seven. I've got you."

As a young child, Dr Katriona O'Sullivan lived in squalor, her parents addicted to heroin. Today she is an award-wining academic who helps other working-class girls overcome barriers to education. Her book, Poor, tells the remarkable story of her ascent from the "trenches" and her determination to inspire others.

Katriona O'Sullivan recalls a time she came face to face in a lecture hall with an 18-year-old "poshie" she once served dinner to.

"Oh my God, wait! It's you, isn't it?" the girl says, clearly astonished. "You were my dinner lady!... But what are you doing here?"

"Ah, come on," Katriona replies. "Did you not know dinner ladies have brains?"

Now 46, a married mother of three and a lecturer at Maynooth University in Dublin, she acknowledges her background makes her a "rarity" in academic circles.

"I actually feel really privileged to have lived through the life that I've lived and I do feel like I can help other people," she explains.

"If there's another girl or a woman who is struggling with themselves and they read my story and they feel a little bit more hopeful, I think it's worth it."

Katriona, aged 13, sitting in front of her mum Tilly at home in Birmingham

Poor, published by Penguin, is a vivid retelling of how Katriona flourished, despite her beginnings.

One of her earliest memories is of finding her father comatose, a needle in his groin, in the bedroom of their Victorian terrace in Hillfields, Coventry.

The paramedics who attended were scornful, taking little care with his limp body. "I asked them if my dad was dead and they just ignored me and kind of looked down their nose at me," she says.

It was a marker of disdain she would go on to encounter from teachers, social workers and police officers and she believes there is a "generic judgement" of children and adults in poverty.

"That we're moral-less or careless or that we don't deserve care and respect and like everybody else," she says.

"I know my parents let us down, significantly," she writes in her book. "But the world around us let us down too, and in a way that is worse."

'Pockets of sunshine'

She is keen to point out hers is not a rags to riches tale, but one of complexity, riddled with set-backs.

"I grew up with that kind of feeling of hunger, but not just hunger for food," she says. "With a hunger for care, for kindness, for acknowledgement, for information, for stimulation.

"I think that people in privileged positions need to really understand, like, how far reaching poverty is. And how it can affect your whole life."

She loved her parents, who are both now dead, and her own research has deepened her understanding of their struggles. "Addiction is a mental illness. It's not a choice, it's not a moral issue," she says.

There are memories she wants to hold on to, "pockets of sunshine in the storm", such as when her mother Tilly, a free-spirit who loved to dance, soothed her after she was struck by a car, aged four.

"I loved you," Tilly told her one day, during a phone call before she died. "But I suppose I loved drugs more."

Father, Tony, was an addict but also a charismatic and educated man who introduced his daughter to books.

When she was accepted on her foundation course at Trinity University, Dublin, he hailed it: "The best news I have ever had."

'A constant fearful feeling'

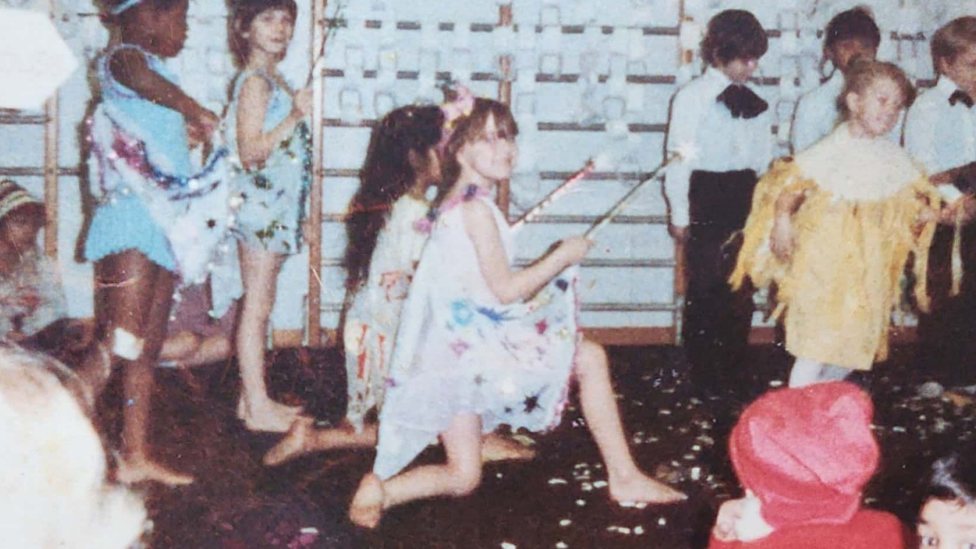

At Southfields Primary, Katriona was an adventurous girl who loved to play football and sing

Southfields Primary is a short walk from the house in Vine Street, in a vibrant multicultural area which remains one of Coventry's poorest.

In the early 1980s, Katriona's parents were in the grip of heroin addiction. For a time, every spoon in the house was singed black, from burning gear.

Around this time Katriona started school, her stomach in knots with anxiety.

"I'm expected to learn to read and write and literally I'm sitting there just worried about what is happening to my mam at home, are the police at the door, is my dad being arrested, is my mam alive?" she says.

School dinners were often her only meal of the day. And a "wonderful, lovely" nursery teacher, Mrs Arkinson, the first to sow in her seeds of self belief.

"I used to just roll out of bed, no washing, no toothpaste," she says. "She didn't focus on what words I knew, the maths, all that other stuff. She focused on trying to build me up a little bit."

Katriona went to primary school in Hillfields, Coventry, and secondary in Sheldon Heath, Birmingham

Mrs Arkinson taught Katriona how to wash herself in the school toilet and brought her fresh pants every day.

"That lives on, having care like that in your childhood," Katriona says.

In later years, Katriona encountered different kinds of teachers, who would make disparaging comments and shame her for not having her own pen.

"They don't realise what a teacher does lives with you for the rest of your life," she says.

'Pockets of sunshine'

When Katriona stayed with Louise she would "cook all the food in the freezer" and relish the chance of a hot bath

After a spell in jail for selling drugs, Tony moved the family to Stoney Stanton Road for a fresh start, then later to Sheldon, Birmingham.

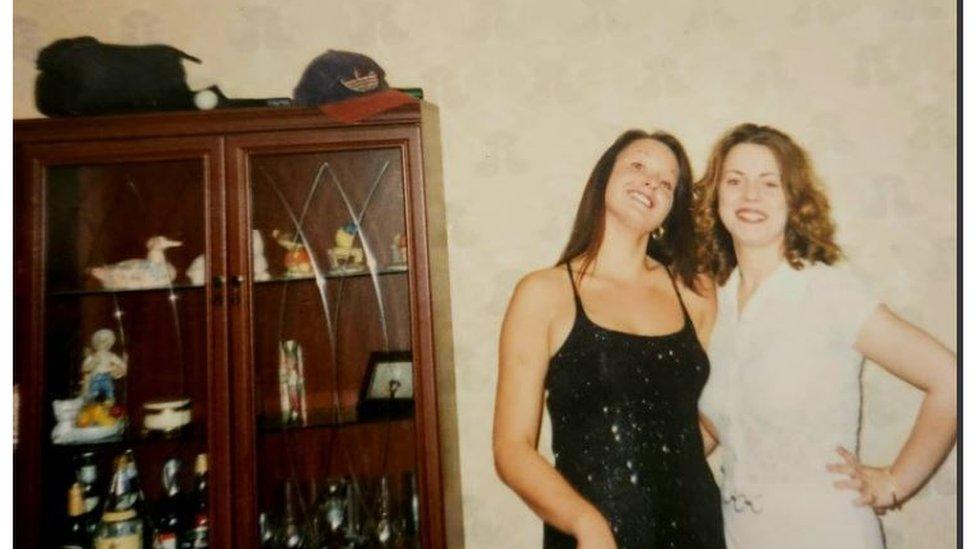

In Sheldon, Katriona met her best friend Louise. Today they remain tight-knit, often in stitches in each other's company.

"We did wag school a lot and get caught a lot," says Louise. "But all I remember about our teenage years is just laughter and that we were there for each other."

The girls hung out by the local Kwik Save, keeping watch while boys broke into cars and went joyriding. Katriona was arrested for fighting, stealing and drugs.

"At the end of the day what other options did I have?" says Katriona. "The bar was set in terms of, 'look just finish school'. That was a success for me. So I suppose it was natural for me to become this wayward teenage girl and hang out with the craziest kids on the road."

Louise and Katriona are still close, 30 years on

One secondary school teacher, Mr Pickering, went out of his way to encourage the teenager's love of books and in his English classes she thrived.

Later, after Katriona dropped out of school, pregnant at 15, he would turn up at her door to encourage her to take her English and maths GCSEs.

Writing the book has helped Katriona feel compassion for her teenage self, who left school believing she was stupid.

"Her in a shell suit in the nineties, with her hair half-up, half-down. Angry, smoking her Benson and Hedges, thinking that she's grown. I've actually learned to love her again."

Katriona and son John, in their council house in Birmingham

Forced out of home while pregnant, she squatted for a time in a Birmingham high-rise, before social workers moved her and son John to a mother and baby unit.

Once in her own flat she tried her hardest to play house, laughing as she remembers spending her grant on a wall unit and ornaments, because that was what "good people" did.

But it was a tough time; and after splitting with her boyfriend she sank into despair.

"The trauma I'd been through, the role models I'd had, the poverty. The weight just piles up on top of each other," she says. "And so I found myself just escaping, drinking, drugging. I actually became very, very like my own parents."

Louise remembers how worried she was at this time, when her friend seemed to be on "self-destruct".

"We tried, everyone tried, but there was no getting through [to] her. And that's when I got really concerned. And the best thing she could have done was to leave here and and go to Ireland," she says.

Katriona and John outside her council house in Birmingham, before they moved to the Republic of Ireland

'Stepping stones'

Katriona considers herself lucky to have arrived in the Irish republic in the 90s, when the country was in an economic boom, with money to help disadvantaged residents.

Her parents had moved to Clontarf, Dublin, and Tony had given up drink and drugs for good.

"I didn't go from extreme poverty to wellness in a blink of an eye, but the fact that my dad had this home there and he was more secure, and my son was more secure. Really I suppose that was the beginning for me of making that transition to where I am today," she says.

She underwent a period of rehab and started regular free counselling sessions while working first as a cleaner and later as a dinner lady.

She enrolled in a free parenting course and a theatre course, "guzzled" up the information and wanted more.

The turning point came when she bumped into an acquaintance while crossing O'Connell Bridge.

Karen, a single mum who was also brought up in poverty, revealed she was studying law at Trinity after completing a foundation year for socially and economically disadvantaged people.

Katriona's heart started pounding and she knew with certainty she wanted that too. She marched directly to the office to apply.

Back in the classroom, she felt an overwhelming sense of being on the right track.

"I'm not this broken person who needed fixing and 'middle-classed'," she says, looking back. "I have skills, amazing skills. You just had to empower me so I could use them."

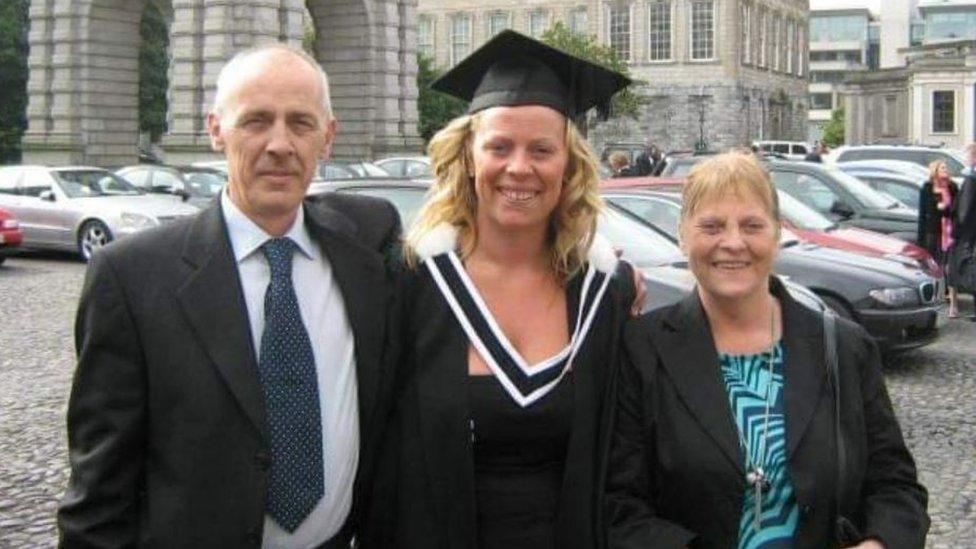

After the foundation course, she was accepted on to a psychology degree, graduated with first-class honours and later completed her doctorate.

'Pathways out of poverty'

Katriona pictured with parents Tony and Tilly, at her undergraduate graduation from Trinity University, Dublin

Katriona credits a few important people, including Mrs Arkinson and Mr Pickering, with nudging her back on track when things got tough - a series of "stepping stones" across a river.

"I didn't climb out of the trench myself - I was pulled out," she writes.

She also acknowledges the funding and schemes that provide "pathways out of poverty".

In Ireland, she leads a €1m euro project to help working-class girls access STEM careers and strongly believes the education system needs to do better.

"There's so many people who have been under-served, so many people with potential who can actually change the world," she says.

Best friend Louise says she always believed Katriona would find success.

"What she's achieved, I couldn't be prouder," she says. "I'm so glad how she's turned her life round and what she's become and I know [her] mum and dad would be."

Follow BBC West Midlands on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to: newsonline.westmidlands@bbc.co.uk, external

- Published13 April 2023

- Published30 April 2023