WW1 soldiers' writing unearthed in Somme tunnels

- Published

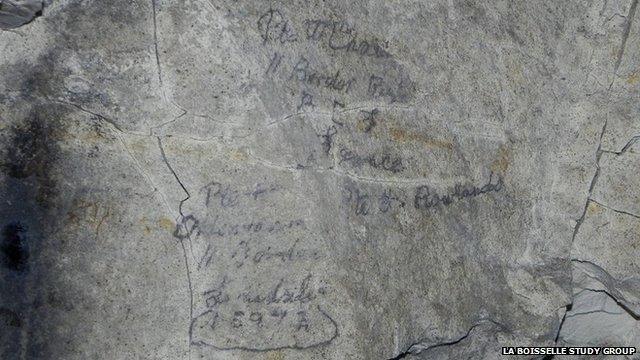

This graffiti is from two of the soldiers, Pte Obadiah Henderson and Pte William Chard. The messages read: "Pte Obadiah Henderson 11 Border Lonsdale 15272" and: "Pte W Chard 11 Border Regt B.E.F France"

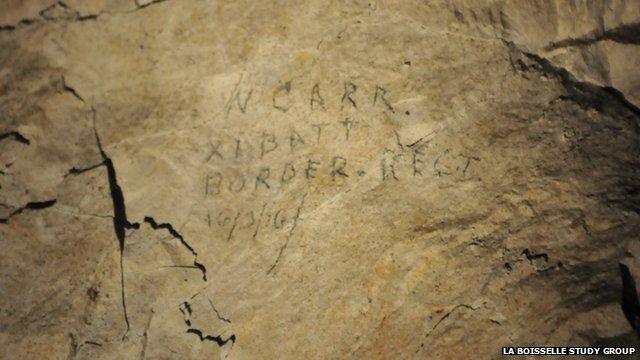

This message from Pte William Carr reads: "W. Carr XI Battalion Border Regt 16/3/16"

Archaeologists have uncovered a labyrinth of World War One tunnels left untouched for nearly 100 years and found poems and the signatures from three soldiers from a Cumbrian regiment. But who were those men and what does this find tell us about their experiences?

Under the site of the 1916 Battle of the Somme in northern France lie hundreds of artefacts, including ammunition and discarded food tins. And on the walls are perfectly legible signatures and poems written in pencil.

"It is such an amazing piece of history and it's so fresh," said genealogist Glen Phillips.

"The signatures have been there for nearly 100 years and because the tunnels have been sealed up, they are as fresh as the day they were made... like a doodles on a notebook these days."

Historians and volunteers have spent the past few years in La Boisselle exploring this part of the Western Front which has remained untouched since the end of WWI.

An appeal is now on to trace the descendants of the men who scribed their personal messages there.

"When I first saw them I was blown away," added Mr Phillips, who is part of La Boisselle project.

"The thought of being able to share that with some of the families of some of those men is what really motivates me and drives me on to do this research."

Underground service

The Somme was not only one of the bloodiest battles of World War One, but one of the bloodiest in history.

The main battle is believed to have resulted in more than 1.2 million casualties, but a group of soldiers fought their own private hidden war underground.

The tunnels, 80ft (24m) down, were dug so that troops could plant explosives below enemy lines.

Most of the British work in the tunnels was done by miners, many of them from the north of England, but a lot of infantrymen were pressed into service underground too.

The three messages on the tunnel walls are from Privates William Carr, William Chard and Obadiah Henderson who all left Carlisle to go overseas with the 11th Lonsdale Battalion in November 1915.

All of these men helped the tunnellers prepare for the Battle of the Somme and all attacked on the first day of battle on 1 July 1916.

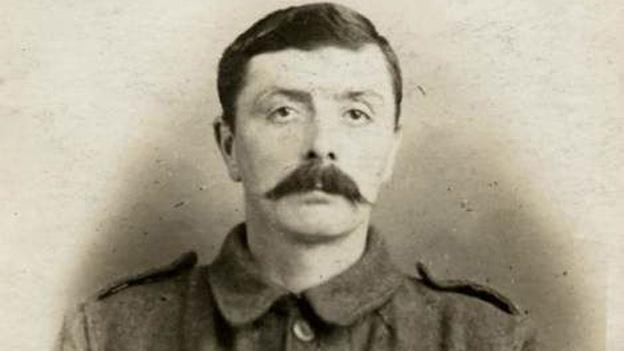

Pte Obadiah Henderson was from Riding Mill in Northumberland and worked as a farm labourer before volunteering to go to war.

Pte William Chard was a joiner from Longtown, Cumberland. Both of these men survived the Battle of the Somme and returned home after.

Pte Carr was wounded on the first day of battle and returned home to Carlisle to recuperate after being shot in the leg.

He then returned to war in the Battle of Arras, serving for the 2nd Battalion, during which he suffered fatal wounds and died on 24 June 1917.

One of the poems found, which is not attributed to any of the men, reads: "If in this place you are detained, don't look around you all in vain, but cast your net and you will find, that every cloud is silver lined. Still."

'Absolutely fascinating'

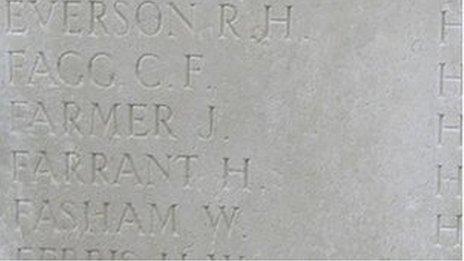

Stuart Eastwood, curator of the Border Regiment Museum at Carlisle Castle, is now helping La Boisselle Project to try and find the soldiers' descendants.

He said war diaries from their time in France stated the three men were providing working parties for the royal engineers and there was "no mention" of them working underground.

"The fact that the names of these three soldiers were found scrawled in pencil on the walls of one of the chambers during the excavation work is absolutely fascinating.

"It means that they weren't just working parties for the royal engineers, these were ordinary infantrymen who were underground backing up the tunnellers and no doubt hauling bags of rubble as well.

"They were taking the same risk that the tunnellers faced, so if something went wrong underground, whether it was a natural thing like a collapse or fighting underground, they would be there as well."

About 90% of the Lonsdale Battalion came from Cumberland and Westmorland and few numbers from County Durham, Northumberland and Lancashire.

Mr Eastwood said it would be "absolutely marvellous" to find the descendants of the men.

He said: "Anything like this is really important, it's another little snippet that can help build up the picture of what happened during WWI.

"It was very local and somebody would know somebody who had served or who was serving, so it was very poignant indeed."

Peter Barton, author and historian for La Boisselle Project, said: "Finding graffiti like this, particularly names, is probably the most thrilling part of this project... to find the names of the men who actually served here and then to be able to try and find their families, that gives it an entirely different dimension.

"Very often we think of World War One as something rather impersonal, we talk about it in tens of thousands of casualties, but each one of those was a man with a history and a legacy.

"I bet there wasn't a day went past when they didn't think about these tunnels."

- Published14 January 2014

- Published1 January 2014

- Published4 October 2012

- Published2 December 2013