Underground journey to find WW1 Somme tunnel digger's grave

- Published

Lesley Woodbridge: "We've just made the very last journey he ever made"

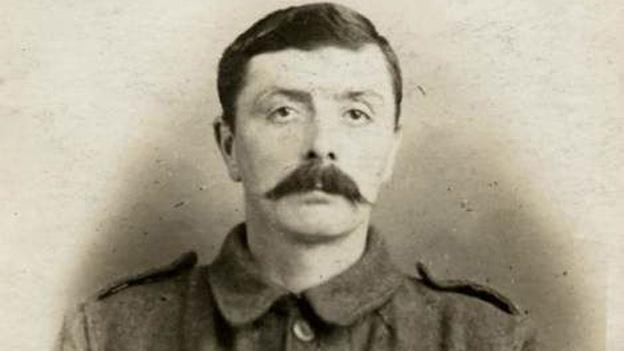

Sapper William Arthur Lloyd was killed by a German mine while tunnelling below the Somme battlefield in 1915. Now his great granddaughter has retraced his steps to stand just feet from where he died - and where his body still lies.

The Somme, in northern France, was not only one of the bloodiest battles of World War One, but one of the bloodiest in history.

More than 1.2 million men are believed to have been killed or injured during the main battle but below ground a group of soldiers, including Sapper Lloyd, fought their own private, hidden war.

Sapper Lloyd's family, back home near Wrexham, knew little about what happened to him, other than he was killed by a German mine.

His great granddaughter Lesley Woodbridge, of Telford, Shropshire, spent seven years investigating his death.

On Sunday, with the help of a team of archaeologists studying the La Boisselle tunnels below the Somme, she descended 80ft (24m) and crawled along tunnels that in all likelihood her great grandfather had helped dig.

"We've just made the very last journey that he ever made and now we're standing where he actually rests. That has to be emotional," she said.

"I never even thought I would even find out what part of France he was in, so to be standing here, just a few metres away from him, is just incredible."

'Historical first'

Ms Woodbridge, 59, said it marked the end of what at times felt like a futile search for her relative.

But it is also a historical first, according to Peter Barton, who led the group studying the network of tunnels at La Boisselle.

"This is hugely significant. I've just shivered thinking about it, because this is the first time ever that a relative has been able to visit these places," he said.

"You can't do that for men on the surface, who are lost in battle, because you simply don't know where they are.

"But of course in the tunnel wars it was so constrained and constricted and so well documented, we know exactly what happened, at what time and what the results were."

Sapper Lloyd was a miner from New Broughton in north Wales, who joined the 179th Tunnelling Company in 1915.

In October of that year he was sent to the Somme, only to die six weeks later in a German explosion far below No Man's Land.

Aged 37, he left behind a wife and six children.

William Arthur Lloyd died in an explosion on 19 December 1915, 80 ft below the Somme battlefield

A 50ft ladder used by tunnellers has been replaced with a winch and bosun's chair. In all, some 150,000 men served underground during WW1. The La Boisselle group has identified 38 bodies in the area.

The team had to crawl the last few metres through the chalk tunnel to where Sapper Lloyd died

'An obsession'

Ms Woodbridge said he had time to write one letter back home, although he was not allowed to explain what he was doing, nor where he was.

In a section of it, he wrote: "Dear wife, children and mother, just two or three lines to let you know that I am quite well.

"All I can tell you is I wish the war was over. It's a monstrous one. I am still thinking of home, the weather here is awful and cold.

"Wishing you all a merry Christmas, but I shan't be home for it. From your husband William Arthur."

Sapper Lloyd was not to see Christmas.

The family received a letter confirming his death, but little else.

Almost a century later, Ms Woodbridge said the search for her great grandfather had developed into an "obsession".

"You can spend so much time looking, just trawling through information and finding nothing and getting really fed up with yourself and then suddenly you find something and it's just such a great feeling.

"I just wish my grandmother and other members of the family were still around so they could see the results."

One member who is still alive, but not able to make the trip herself, is Lesley's 88-year-old mother Thelma Roberts, who still lives in Wrexham.

She broke down in tears as her daughter made her way along the tunnel and spoke to her on the phone.

Ms Woodbridge's hunt began in 2005. Searching online she discovered that Sapper Lloyd was named on the Thiepval Memorial, among some 70,000 men lost at the Somme.

However, her enquiries were proving fruitless until she got in contact with Simon Jones at the University of Birmingham.

An expert on WW1 tunnelling, Mr Jones was also connected with the archaeological dig at La Boisselle.

Mr Jones quickly confirmed that Sapper Lloyd was one of five men who died in a counter-tunnelling operation.

'Hidden battlefield'

Members of what became the La Boisselle Study Group were invited, by the landowners, to investigate the site two years ago.

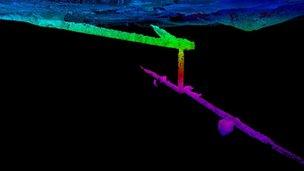

Seven kilometres of tunnels are now accessible, including the area around W1 shaft

"There was a little hole in the field and we slipped into the hole and it opened up into this labyrinth of tunnels," Mr Barton said.

"We found that rather than being completely destroyed they were very well preserved."

Today, the team can access almost four miles of tunnels, on four levels, beneath what is just a five acre site.

Among those now accessible is W1 shaft, where, in a small gallery, Sapper Lloyd died.

"It's a sobering experience, because they're not just tunnels, but a hidden battlefield," Mr Barton said.

"We have a perception of a World War One battlefield, but this is an underground, private, clandestine war and William Arthur was a part of it."

Using documents from the British, French and German archives, the study group was able to piece together what happened.

In one German report on 23 December 1915, a deputy company commander wrote that a microphone first detected British miners working nearby on 18 December.

Lesley Woodbridge speaks to her mother Thelma Roberts live on air from the tunnels

A 750kg explosive charge was detonated immediately, presumably killing one group of miners. The company then started to prepare a 12,000kg charge.

Oberleutnant Sihler wrote: "After six and a half hours' work, the charge had been laid in the mine chamber, and by 12:30 tamping and timbering had been completed and the mine was ready to be fired."

It was detonated at 16:00, killing Sapper Lloyd and his fellow miners. Despite its depth, it created a crater 40m wide on the surface.

The war underground has gone largely unrecognised, while history has focused on men pouring over the tops of trenches into a hail of bullets and artillery shell explosions.

The La Boisselle Study Group hopes to remedy that, although there are no plans to open up the gallery that is now a grave for Sapper Lloyd and his four colleagues.

For Ms Woodbridge, the group has given her a unique insight into her great grandfather's brief war and death almost 100 years ago.

Down in the tunnels she left behind an urn containing soil from the colliery where her great grandfather first worked - "a little bit of home for him".

"This is the end of the journey for me. There's nowhere else I can go is there?" she added.

"I can't get any closer to him."

- Published2 December 2013

- Published29 November 2013

- Published11 November 2013

- Published10 June 2011

- Published4 October 2012

- Published3 November 2011