Furness hospital baby deaths report due to parent power

- Published

Joshua Titcombe died nine days after being born at the Furness General Hospital maternity unit

Failures at a Cumbrian maternity unit where a number of newborn babies and mothers died have been exposed. But would these ever have been revealed without the persistence of bereaved families?

Joshua Titcombe was nine days old when he died in November 2008.

He was born at Furness General Hospital in Barrow and was transferred to two other hospitals before dying in Newcastle.

A 2011 inquest found Joshua died of natural causes, but the coroner listed a series of failings by the maternity unit and said staff missed opportunities to save him.

He had developed an infection and died of pneumococcal septicaemia - a form of blood poisoning.

It would later turn out he was one of three babies and a mother who had died within months of each other as a result of failings in the maternity unit.

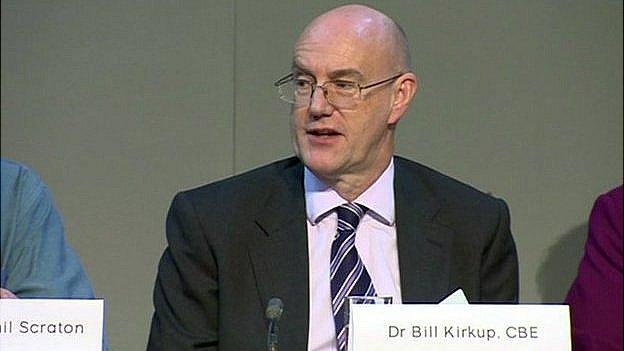

The bereaved families' struggle for information eventually led to a review by Dr Bill Kirkup, which has now been published.

Joshua's parents, James and Hoa Titcombe, began with a complaint to the University Hospitals of Morecambe Bay NHS Trust (UHMB) in 2008.

Failings at the Furness General Hospital in Barrow led to the deaths of baby and mothers

An investigation found standard checks and record keeping were not carried out and midwives did not recognise his low body temperature as a symptom of sepsis, a potentially life-threatening condition where the body's immune system goes into overdrive.

If this had been spotted and antibiotics given at an earlier stage, he probably would have survived, it said.

But Mr Titcombe was not satisfied with the report, and was particularly concerned that Joshua's observation chart, which had a record of his temperature on it, had subsequently gone missing.

Another report by the strategic health authority, NHS North West, in May 2009, found the record-keeping in Joshua's case had been unsatisfactory, but the quality of care he had received had been up to standard.

Mr Titcombe then went to the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman (PHSO), which deals with complaints about the NHS and other public bodies, and the healthcare regulator the Care Quality Commission (CQC).

The PHSO refused to investigate initially and the CQC found maternity services at the hospital fully compliant with standards after an inspection in 2010.

The trust itself had commissioned an external report in 2010, by nursing expert Dame Pauline Fielding, which described the team as "dysfunctional".

The CQC knew the trust had commissioned an investigation following a number of baby deaths.

The Fielding report was received by trust managers in March 2010, just weeks before it was registered as safety compliant by the CQC. It was not publicly disclosed at the time - the trust did not make the report public until 2011.

Later that year the trust was awarded foundation status, giving it greater independence from government and effectively endorsing the way it was managed.

Liza Brady and Simon Davey had a similar struggle for answers over the death of their son, Alex.

He was stillborn with the umbilical cord around his neck in September 2008. An inquest later found midwives had failed to involve doctors early enough.

His parents complained to NHS North West five times and to the PHSO twice before the ombudsman eventually upheld a complaint in 2013.

It also upheld complaints around the same time from Mr and Mrs Titcombe and Carl Hendrickson, whose wife Nittaya and son Chester died in the maternity unit in July 2008.

In all three cases the ombudsman found that failings in midwifery had led to the deaths and that NHS North West had failed to investigate properly.

Mr Hendrickson also received a six-figure sum in compensation from the trust.

Dr Bill Kirkup has spent nearly two years chairing the Morecambe Bay investigation

Ms Brady and Mr Davey followed the Kirkup hearings closely, attending more than half of the interview sessions.

Ms Brady said: "It has been difficult to listen to everything that's been going on inside the hospital but has also given us an in depth view of what kind of things have gone wrong.

"There seems to be major problems with staffing, finance, who is responsible for different roles and that to me has been a great concern to listen to."

The pair said they pursued the problems in honour of their son, providing him with the voice and defence he never had.

Ms Brady said she was "anxious" about how the findings would be used.

She said: "I want the Kirkup report to implement real change across the NHS and stop putting a plaster on things, we need real change.

"It would bring closure, for the past six and half years it's been a battle.

"We've been Alex's voice, if everything's uncovered, the dishonesty and major failings that led this to happen, then we have done our duty.

Mr Davey said the investigation had uncovered a culture of deniability in the NHS at the time.

He said: "More than anything it's a denial of a problem and the culture allowed the problem to continue, because nobody was taking any accountability for the problems that were happening.

"It was about being the voice of our son and defending our son, over time we've become quite burdened with other issues, it's got to a bigger scale than we ever imagined and we've taken the burden of other families which has made our lives a lot more difficult."

In 2013 it emerged more than 30 families were taking legal action over deaths in the maternity unit.

It was later that year that Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt announced there would be an independent inquiry, looking at the entire period from January 2004 to June 2013.

This was several years after parents began raising concerns, but found some authorities unwilling to investigate properly.

- Published18 February 2015

- Published11 December 2013

- Published11 December 2013

- Published18 July 2013

- Published24 June 2013

- Published25 October 2011

- Published8 June 2011

- Published7 June 2011