Tour de France: The disastrous 1974 Plymouth stage

- Published

Forty years ago the world's biggest bike race crossed the channel for the first time. However, the slightly strange Plymouth stage was such a disaster the Tour did not return to the UK for another 20 years. But was British ignorance to blame?

"We were treated like illegal immigrants," says former professional cyclist Barry Hoban, of the welcome the riders got from customs officials at Exeter Airport.

With all of them herded into a locked room, he claims he had to kick on the door to get let out.

As one of only two British riders on the 1974 race, the other cyclists turned to the Yorkshireman for an explanation.

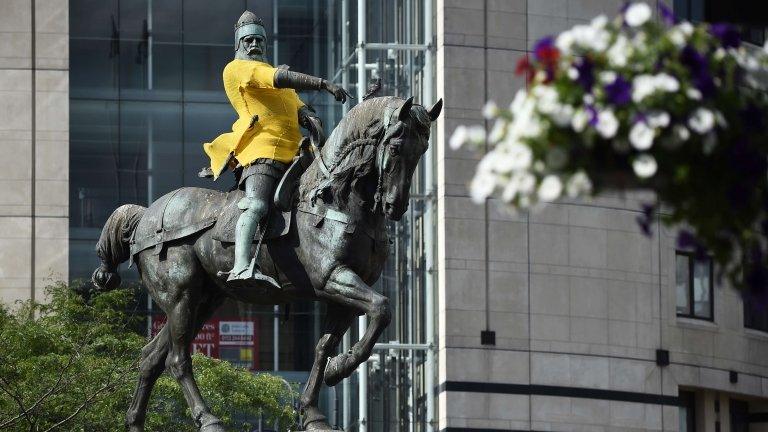

Tour organisers turned down the hills of Dartmoor in favour of the A38

"'Barry, what's happening, what's happening?' they asked, 'It's not my fault!'" he said of the experience, adding: "I was embarrassed to be British."

The race had begun two days earlier in Brest, with Eddy Merckx taking the yellow jersey on the way to his record-equalling fifth and final Tour de France win.

So far, so normal. But the 1974 Tour was unusual in that it strayed outside mainland Europe for the first time.

It had all been the idea of the artichoke growers of Brittany. They had decided a great way to promote their produce in the UK would be to fund the Tour's first ever visit there, in addition to publicising the Roscoff-Plymouth ferry route that had opened the previous year.

But the extension of the entente cordiale was seemingly not reciprocated by the officious British customs.

"I had come to an arrangement with the customs and immigration officials," says Alfred Palmer, the Plymouth City Council employee seconded to organise the stage.

"Come the actual day they let me down stinking."

He had told them the riders would be very tired from having raced 200 km that day and would be keen to get to their hotels as swiftly as possible. However, his pleas for a swift passage through customs apparently fell on deaf ears.

"When I went to see the customs people, and said 'Look, this isn't what was promised'. They said 'You keep out of it. If you want to get yourself in trouble, carry on doing what you're doing.'"

The riders were again held up when trying to leave the country.

"We thought they'd be glad to just shove them on a plane to get rid of them, but they kept them hanging about for a couple of hours, getting all the riders to fill in forms," says Mr Palmer.

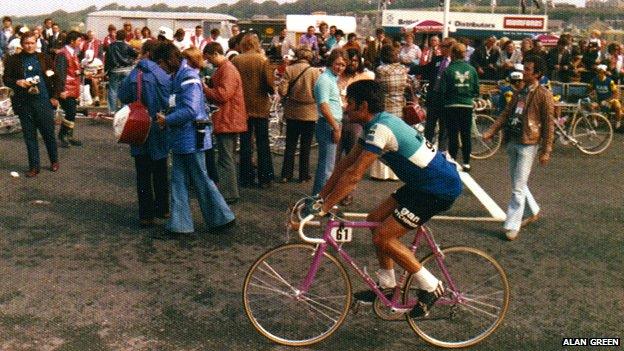

Barry Hoban (in blue) sprints through the finish line - he came ninth on the day

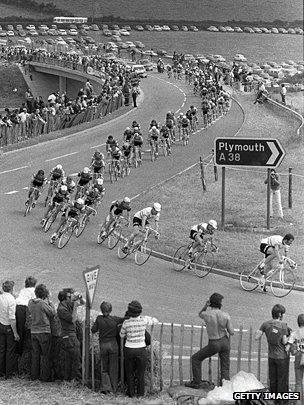

The Tour's visit enabled fans a rare glimpse of their heroes in the flesh, such as Raymond Poulidor

The airport customs officials, perhaps unwittingly, helped the event achieve one of its aims - to publicise the convenience of the new cross-channel ferry route.

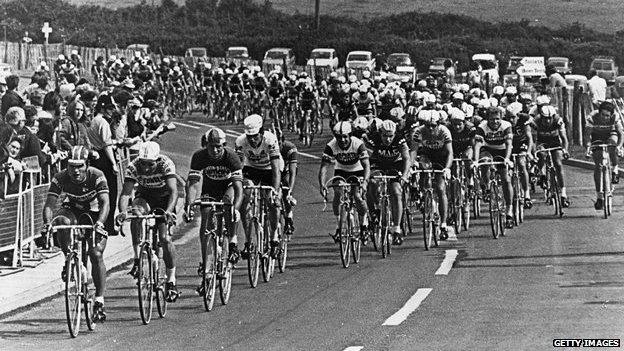

But the transport to and from England was not the only problem. The insipid route of the stage - up and down a short stretch of the recently-opened A38 Plympton bypass - was also unpopular with riders.

"I've ridden twelve Tours de France and that was the most boring stage I've ever, ever ridden," says Hoban, who went on to win stage 13 of that year's race and eight stages of the Tour in total.

"The Plympton bypass was five miles long and all you had were people at either end, and no-one in between.

"You need a disruption in the road make-up for a rider to jump away. It was just a bunch sprint. And it wasn't a good bunch sprint, because you came round the last roundabout and - boomph - the finish was there."

Long before Wiggomania, an unsolicited visit from the Tour de France was a bolt out of the blue for a country with no mainstream interest in the sport of professional cycling.

At the time, it was unheard of to close the roads for a bike race in this country, let alone a French one.

Received opinion is the British just did not "get" the spirit of the race, so stuck it out on an isolated stretch of road for fear of causing too much of a disruption to other traffic.

Dutch rider Henk Poppe was the surprise winner of the stage, retiring the following year after only two years as a professional

Eddy Merckx (in white) went on to win the Tour for a record-equalling fifth time

But, according to Mr Palmer, this was not true. The authorities had indeed been initially apprehensive but had given the go ahead with the backing of Denis Howell, the Minister for Sport.

It was in fact the French organisers, Felix Levitan and Jacques Goddet, who chose the Plympton bypass route.

He maintains they had been given other options, including a circuit of Burrator reservoir or on the open roads of Dartmoor - a far more scenic and demanding route.

"I think they had a preconception that they wanted to do something like on the bypass," he says. "They sort of went through the motions of looking at the other places we showed them. They had a predetermined idea of what they wanted to do."

Revealing plans for an English stage for the first time to journalist Geoffrey Nicholson in 1973, Mr Goddet had stated his desire for the race to go over Dartmoor. So what changed his mind? Why go to the effort of bringing the world's biggest bike race, and largest annual sporting event across the Channel just to trudge up and down a bypass?

Retired cycling journalist Keith Bingham, who was at the stage, confirms the French organisers had been offered a big circuit taking in Dartmoor.

"Tour co-director Félix Lévitan chose the bypass because it made for an easier departure back to France that same day," he says.

Mr Palmer also offers another intriguing theory as to why the French wanted to use the bypass.

"Whilst they would never admit it, we like to feel that they used the Plympton bypass stage as a bit of an experiment, with a view to using the Champs Elysees for the final which has been held ever since in Paris.

"We like to feel that we were a little bit of a trailblazer in helping them come to that decision."

If true, it means the derided Plymouth stage, one that has otherwise gone down as a bizarre footnote in the long history of the Tour, has actually had a lasting influence on it. It's a theory Hoban finds highly amusing.

"Please don't compare the Champs Élysée to the Plympton bypass," he says.

"On big tours, the last stage is a promenade, a presentation of the guys who've battled for three weeks. It's a presentation of the heroes to the public. The Champs Elysees, excuse me, that was up and down, that wasn't easy, and that was one hell of a sprint.

"It doesn't wash with me."

- Attribution

- Published8 May 2014

- Published1 July 2014