Giro 2014: Why do cycling's Grand Tours start in other countries?

- Published

It was two days before the start of the 2012 Tour de France in Liege, Belgium, and Welcome to Yorkshire's chief executive Gary Verity was striding towards a meeting with the Tour's director, Christian Prudhomme.

With a decision on where the 2014 race would start due by Christmas, Verity was wasting no chances to press Yorkshire's case, particularly as it was seen as a left-field pick, and not even the inside choice for a British Grand Depart this summer.

That did not unduly worry Verity, though. The idea of bringing the race to Yorkshire had occurred to him whilst shaving one morning, and he was not about to let anybody nick it from him.

A born salesman, it was somehow typical that he would ask to "borrow" the dog of a passing pedestrian, snap a selfie with the animal on his phone and send it to Prudhomme with the message, "Even the dogs in Belgium want Yorkshire to host Le Tour". It was a Yorkshire Terrier, you see.

Was it that mutt what won it, or was it, perhaps, the more juicy bone of a large cheque?

To answer that we must explore why the Tour de Wherever wants to visit, let alone start in, anywhere other than Wherever, which is exactly what is about to happen in Belfast this week, and in Leeds this July.

The short answer is money. In truth, it is the long answer, too, but with a slight diversion through cycling's limited revenue streams, the need for new audiences and the importance of television.

Let us take the Giro d'Italia first, as its "Big Start" is almost upon us.

This will be the 11th time the race has started outside of the Bel Paese ['Beautiful Country'] but the first time it has left mainland Europe.

The Giro's owner RCS Sport prefers a more discreet bidding process than the Tour's public beauty contests, but Belfast beat a strong domestic bid from Venice and one other unnamed European city that intends to bid again.

If the thought of starting something as quintessentially Italian with three days on a wet and windy island in the North Atlantic - a detour that requires an early start to the race to accommodate a travel day between Dublin and Bari next Monday - sounds odd, it is not as odd as starting the race in Washington DC, which was on the cards for 2012.

The fact that bid was not laughed out of Milan prompted Darach McQuaid, a man cut from the same cloth as Verity, to float the idea of an Irish bid to Ireland's Taoiseach Enda Kenny at a St Patrick's Day party at the White House in 2010.

A former rider who helped bring the Tour to Dublin in 1998, McQuaid comes from the first family of Irish cycling. His brother Pat ran the International Cycling Union (UCI) until last year.

In Antrim, Northern Ireland, even the sheep - their wool dyed pink to reflect the colour of the race leader's jersey - are getting into the Giro spirit

So when Kenny told him an austerity-hit Ireland could not afford it but perhaps he should run it by the chaps up north, McQuaid had the connections to make it happen, even when the Italians told him he would need more cash.

With Northern Ireland eager to tell the world there is more to the post-Troubles dividend than The Game of Thrones,, external McQuaid was able to rustle up a sweetener of almost £5.5m. Most of that came from Discover Northern Ireland and Belfast City Council, but significant contributions came from the Republic's tourist board, Dublin City Council and Mediolanum, an Italian bank with an investment arm based in Dublin.

"There are three reasons for taking a Grand Tour abroad," explains McQuaid.

"First, they want to share the national event they are very proud of with new 'tifosi' [fans].

"Second, and closely related to that, they want to grow their brand.

"But finally, there is the financial consideration: they can get more money from foreign starts."

Giro d'Italia (9 May-1 June) | Tour de France (5 -27 July) | |

|---|---|---|

21 | Days | 21 |

3,445.5km | Distance covered | 3,500km approx |

22 | Teams | 22 |

198 | Riders | 198 |

249km | Longest stage | 237.5km |

21.7km (stage 1) | Shortest stage | 54km (stage 20) |

2758m | Highest point | 2360m |

171 countries | TV coverage | 188 countries |

So RCS Sport got more than Venice and at least as much as other European city was offering, and Belfast got the start and finish of two stages of the world's second biggest bike race. What that means in practical terms is a week of full hotels and restaurants, months of publicity, and a weekend when millions of people around the world will see exactly what your tourism chiefs want them to see.

Putting a figure to these benefits is more art than science, but French venues bidding for Tour visits often talk about a six-fold return on investment. Another rule of thumb is that each fan on the roadside is worth about two euros to the local economy, which comes to one million euros a day at the Tour.

We try to put a more mathematical spin on it by drawing up economic impact assessments. When Britain last staged the start of one of cycling's three-week extravaganzas, the 2007 Tour, London got a prologue, with a second stage going from the capital to Canterbury. That was worth an estimated £88m, with £73m of that flowing to London.

This year's estimate for the three days of the Grand Depart, the two in Yorkshire and one between Cambridge and London, is for at least £100m. That would be a four-fold return on the £27m total budget.

The people of Skipton in north Yorkshire are getting ready for the Tour de France Grand Depart by decorating their canal boats

How much of that pot has gone to the Tour's owners, the family-run Amaury Sport Organisation (ASO), is a secret, although Yorkshire's contribution is believed to be in the region of £4m.

There are some tax-payers who think that is a steep price to pay, particularly when they find out about the road closures, but when you consider the bigger picture, these races are quite cheap.

After all, the Giro will be watched by an estimated 500,000 people on the roadside in Northern Ireland and the Republic, while the Tour's English crowds could top three million, none of whom will have paid a penny for the privilege.

You could argue that a sport that cannot sell tickets, or control where its "customers" buy refreshments or souvenirs, should be charging more than a combined £10m in fees for six days of world-class sport.

But pro cycling is not as healthy as it should be, and is probably asking for as much as its current markets will pay, hence the desire to find new ones.

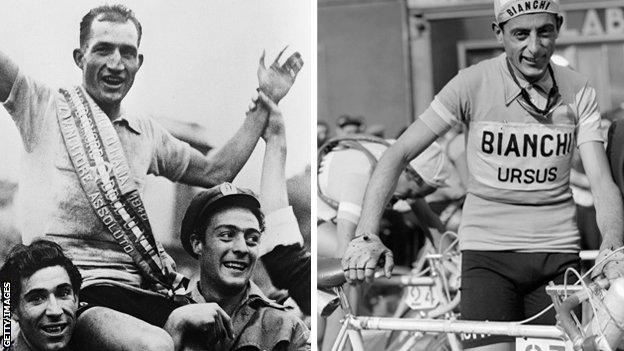

Let us take the Giro as an example. There was a time when it was on a par with the Tour, particularly just after World War II when the duels between two great but very different Italian champions, Gino Bartali and Fausto Coppi, gripped sports fans across Europe.

Bartali (left) won the Giro d'Italia three times (1936, 37 and 46) while Coppi, born five years later, was victorious on five occasions (1940, 47, 49, 52, and 53)

But by the 1980s there were clear signs the French race had pulled away from its younger Italian counterpart. One reason is that the Tour had always been more international than the Giro, and was now fixed on the concept of "mondialisation".

The boss of the Tour at the time was obsessed with breaking America, a feat that was eventually achieved not through transatlantic flights but by the lasting efforts of Greg LeMond, and the fleeting (but undeniably more resonant) achievements of Lance Armstrong.

The Tour had already started abroad twice before the Giro got around to trying it in 1965, and even then they only went to San Marino, the tiny enclave in Italy's Apennines. Foreign riders had won 20 Tours by the time Switzerland's Hugo Koblet became the first non-native to claim the Giro in 1950.

"When I took the Giro to the Netherlands (in 2010) and Denmark (in 2012) I wanted to make it a global event," explains former Giro boss Michele Acquarone.

"Cycling was slowly becoming global, but the Giro was local - it wasn't even European!"

Having tried four foreign starts between 1965 and 1974, the Giro did not go abroad again until 1996. It has now settled into a pattern of alternating foreign and domestic starts, but the damage was done in terms of the financial gulf that exists between the French and Italian races.

Acquarone points to the value of the Giro's US TV deal as an example. ASO gets about £6m from NBC for the Tour's broadcast rights, which is 10 times more than the Giro's income from American TV.

But to put that in context, the US rights for four days of golf's Open Championship are worth more than double than the Tour's, and Wimbledon's cost four times as much.

"In terms of global TV, cycling is small and the Giro is even smaller," says Acquarone.

Giro d'Italia: Roche ready for 'long haul' in Grand Tour opener

One of the legacies of taking the Giro out of its comfort zone are new TV deals in the Netherlands, Denmark and now Ireland. Television brings new fans, and they bring new sponsors.

Both the Giro and Tour routinely trumpet how many people are watching: the latest claims are 775m viewers in 171 countries for the Giro; and a barely credible 3.5bn people from "more than 188 countries" for the Tour.

The irony here is that both races were created to sell newspapers, a function they served for decades, but not anymore. Now it is all about the moving image, and that sometimes means taking your event to new broadcasters, in much the same way that US pro sports leagues have been courting the UK market so aggressively.

But televising cycling is notoriously expensive, so much so that some of cycling's brave new worlds - sport-hungry locations like Beijing, Dubai and Qatar - even subsidise the production costs so broadcasters pick up the races. The upshot of this is that Prudhomme's ASO only makes money from two of the dozen or so European bike races it runs: the Tour and Paris-Roubaix, cycling's most celebrated one-day race.

For all that men like Acquarone and Prudhomme want to translate cycling's current popularity outside the traditional heartlands into television contracts that reflect those bold statements about viewing figures, they know they can only push so far and so fast.

There is a spectre at this feast, too - alluded to earlier. Cycling's commercial appeal has been badly damaged by decades of doping scandals.

There is no getting around that, and if it means the Giro, Tour and Spain's Vuelta are now available at a relative discount to all potential bidders, then some shared good might come from the years of bad blood and false messiahs.

- Published8 May 2014

- Published2 May 2014

- Attribution

- Published7 May 2014

- Published4 September 2014

- Attribution

- Published8 May 2014

- Published7 May 2014

- Attribution

- Published1 October 2013

- Published19 July 2013

- Published19 July 2013

- Published19 July 2013

- Published19 July 2016