Devonport: Living next to a nuclear submarine graveyard

- Published

How dangerous is it to live next to a nuclear graveyard?

They were once at the vanguard of the UK's Cold War effort but much of Britain's former nuclear submarine fleet now lies rusting in Devonport dockyard with its radioactive cargo still intact. But how dangerous is it to live next to a nuclear graveyard?

In a housing estate near Plymouth, mother-of-one Christelle Gilbert confesses she is more than a little worried about her next-door neighbours - 12 retired nuclear submarines.

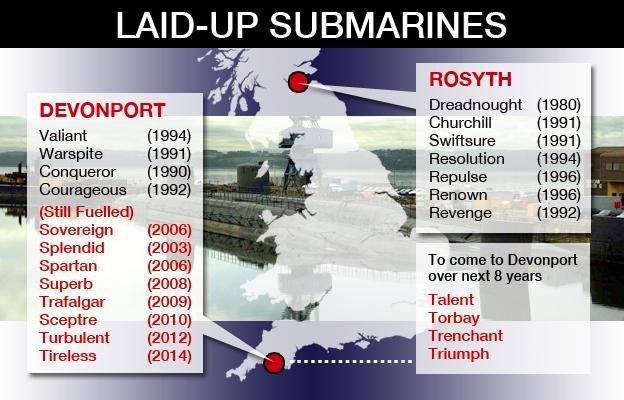

Two months ago, the latest arrival - HMS Tireless - sailed into the base. Like seven of the hulks already there, the Ministry of Defence is still unable to remove her nuclear fuel and four more subs are expected to arrive in the next eight years.

Although defence chiefs insist the subs are safe, some experts have warned of potential radiation leaks. Many residents now just want the subs to go.

"They need to get rid of the submarines, it's disgusting that it is taking so long," said Ms Gilbert.

"It's just too long for the submarines to be sitting there as a potential threat to the city. It's a lack of responsibility on the government's part not top get them moved.

"I have a son and I don't want his future jeopardised by it."

Christelle Gilbert: "It's just too long for the submarines to be sitting there as a potential threat to the city"

Kerry Evans: Submarines put me off living here

Barne Barton estate with Devonport yard in the background

A former Devonport worker, Ian Avent, who still lives in the area, said he was also concerned about safety.

"There are three primary schools within spitting distance of the dockyard," he said. "There has got to be a foolproof process and the dismantling worries me.

"We have had rail trucks going off the track at the dockyard. Luckily they didn't have fuel rods on. If contractors are doing the work I fear they could cut corners."

The queue of nuclear submarines waiting to have their fuel disposed of began in 2002 when the Office of Nuclear Regulation (ONR), then called the Nuclear Installations Inspectorate, told the MoD the Devonport facilities did not meet modern standards.

This has been compounded by the fact the UK does not yet have a suitable facility for disposing of the subs' reactors, which means that those subs that have been defueled cannot yet be dismantled.

"The MoD has had since the 1980s to deal with the legacy of nuclear submarines and they thought it would be a simpler task than it has proved to be," said Peter Burt, a researcher at the anti-nuclear weapons pressure group, the Nuclear Information Service.

"The problem hinges around finding a waste depository - we still have no idea where it will be, or how much it will cost, so we are still a long way from a sensible solution to radioactive waste in this country.

Nuclear graveyards - why do they exist?

No site has been agreed to take the radioactive reactors

Defueling ended in 2002 after regulators said facilities were out of date

Devonport has 12 submarines, four defueled, eight with fuel

Rosyth has seven submarines, all defueled

Oldest submarine: HMS Dreadnought, Rosyth, 1980

Latest submarine: HMS Tireless, Devonport 2014

"Any delay in finding an interim site will leave the submarines there indefinitely, which is a major concern if you live there."

There are about 25 tonnes of radioactive waste - steel which has become radioactive - in the reactors of each decommissioned submarine.

But dismantling cannot take place until there is an agreement on where to take the waste material - and negotiations are still ongoing.

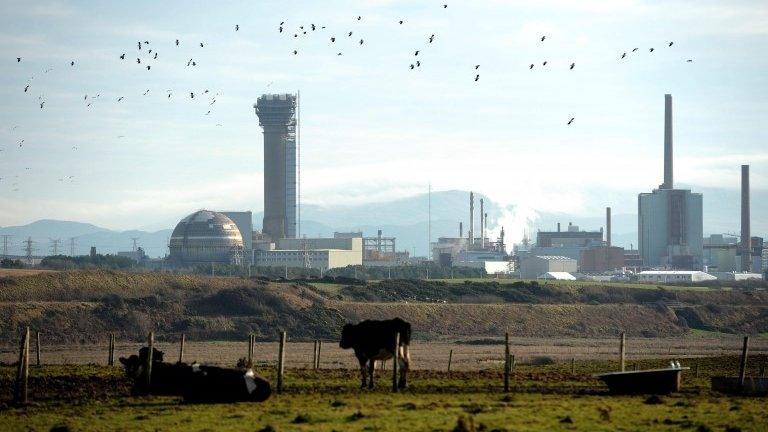

Five possible interim storage sites have now been selected, at Aldermaston and Burghfield in Berkshire, which are owned by the MoD, Sellafield in Cumbria, Chapelcross in Dumfriesshire, and Capenhurst in Cheshire.

Consultation on a site for the interim storage of the radioactive nuclear reactor waste is ongoing

Nuclear engineering consultant John Large, who has advised the government and environmental groups on nuclear issues, said that he believed Sellafield would be the option chosen.

"They want a site that will attract the least public attention," he said. "They all have strong MoD links, but you would not have to develop special facilities at Sellafield."

The MoD said it hoped to name a site for temporary reactor storage in 2015 and begin defuelling "as soon as possible", but Mr Large said the reactors should have been defueled and put into storage years ago.

"The submarines that have not been defueled are a significant risk," he said. "The consequences are enormous.

"To keep submarines in this condition, as floating hulks in the middle of a city of 260,000 souls such as Plymouth seems to be, quite frankly, technical madness.

"The submarines are well past their sell-by date and there is nothing in their design or hull design to suggest a post-operation period of this length.

How do other countries do it?

Reactor materials from US submarines are buried at the Hanford site

USA

The submarines' nuclear reactor compartments are removed and dismantled at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton, Washington. The USA has dismantled about 100 submarines.

The materials are buried and monitored at the Department of Energy's Hanford site, external in Washington.

The reactor fuel is removed and sent to the Naval Reactors Facility in the Idaho National Laboratory. Submarine sections are recycled, returning reusable materials to production.

Disposal of submarines costs $25m-50m (£15m-£30m) per submarine.

Source: US Environmental Protection Agency

Russia

A total of 199 retired nuclear submarines have so far been dismantled in Russia.

Dismantling takes place at the Nerpa Shipyard, in the Kola Peninsula, Zvyozdochka Shipyard in Severodvinsk and Zvezda Shipyard in Bolshoi Kamen.

Spent nuclear fuel is transported by ship and railway to Mayak reprocessing facility near Chelyabinsk, in Siberia, for storage and reprocessing.

The emptied reactor section of the submarine is cut off, sealed and transported to an onshore storage site at Sayda Bay in Siberia and a floating site in the Pavlovks submarine base, close to Vladivostok.

Source: The Bellona Foundation (independent environmental organisation)

France

France has dismantled three submarines at its military base at Cherbourg, where the reactor sections also are temporarily stored.

Source: The Bellona Foundation (independent environmental organisation)

"The US is decommissioning its submarines and the Royal Navy have been real laggards," he added. "You can put anti-corrosive into the system, but you still have a derelict hulk which is rotting away."

Environmentalists Greenpeace are also highly critical of the government.

"If you operate nuclear submarines you are going to have a problem in dealing with the risks and legacy of nuclear waste - that is something that successive governments have failed to admit, and prepare for," said spokesman Shaun Bernie.

"There are major risks with the current policy of storing retired nuclear submarines awaiting decommissioning - the overall problem being that the UK has failed to identify a long term storage disposal option for nuclear waste and that this problem will not be solved within the coming decades.

"Dismantling and removal of radioactive components from submarines at Devonport in addition to hazards such as radioactive releases into the environment will further turn Devonport into a de facto nuclear disposal site."

Devonport in Plymouth, Devon is home to 12 out of service nuclear submarines

Eight submarines at Devonport are waiting to be defuelled

At Barne Barton Primary School, the nearest school to the naval base, staff and pupils practice an annual nuclear emergency drill.

In the "very unlikely" case of a leak, the council has put an emergency radiation leak plan, external on its website advising people to stay indoors and take iodine tablets to thwart the effects of radiation.

Leaflets with the same information were sent in September to residents in the Devonport and Barne Barton area overlooking the dockyards.

Kerry Evans, whose home is a short walk from the yard, said: "When we got the leaflet through the door it put the shivers up me.

"It's quite scary. I have children and my family to think about. If there is an accident it's going to affect everyone round here.

"Plymouth is a beautiful place, but when I read things like it puts me off living here."

Will Blagdon, who owns a boat refitting business in Devonport and is a member of the Devonport Neighbourhood Board, said he believed local people were more concerned about rubbish collections than the submarines.

Mike Gallagher: "If the submarines are looked after properly I don't see a problem"

Nuclear submarines are stored at Devonport, less than a quarter of a mile from homes

"We have to trust in the Navy, the Ministry of Defence and the dockyard to ensure that proper maintenance of the submarines is in place," he said.

"Some people say they should not be so close to the city and built-up areas, but we have had a naval base for more than 200 years and it is part of life here and our heritage.

"Modern submarines require this kind of propulsion and the safety record at Devonport is pretty good."

The MoD said work to modernise Devonport had been "extremely complex" and would "take some time to complete".

It said it spent £700,000 a year maintaining the submarines and "all submarines presently stored afloat are well maintained to preserve them in a safe condition".

"We remain fully committed to restarting the defueling of our ex-Royal Navy nuclear submarines as soon as possible," a spokesman said.

It was "on track" to carry out a test dismantling of a submarine at Rosyth, in Scotland, in 2016.

Meanwhile, the city council, said it was liaising closely with the MoD to ensure the "highest possible" safety standards were maintained.

For Mike Gallagher, chairman of the Friends of Devonport Park which overlooks the base, the main issue is Plymouth's economic future.

The yard is a major employer, keeping about 2,500 services and civilian personnel in work.

"If the submarines are looked after properly and the dismantling is done safely I don't see a problem," he said.

"The word nuclear frightens people, but there is too much 'not in my back yard.'

"It has to go somewhere and it is work for Plymouth which is key."

- Published14 August 2014

- Published25 July 2014

- Published1 July 2014

- Published30 June 2014

- Published19 June 2014

- Published11 June 2014

- Published13 March 2014

- Published13 February 2014

- Published25 January 2013

- Published12 November 2011

- Published28 October 2011

- Published27 October 2011