'Dad said we were going to a dentist, but never came back'

- Published

Following her mother's death, Hayley Kemp was left at a children's home by her father, who had told her they were going to the dentist. She was seven.

Hayley, now 55, went on to have a chaotic childhood - at one point sharing a room with a sex worker after being placed with her by the council. She was also sent to a young offenders institution despite not having committed any crime.

However, she remembers her time in the children's home in Plymouth as the happiest period of her childhood - and she explains how her early experiences would later help to give her life meaning.

'My stepmum used to beat and starve me'

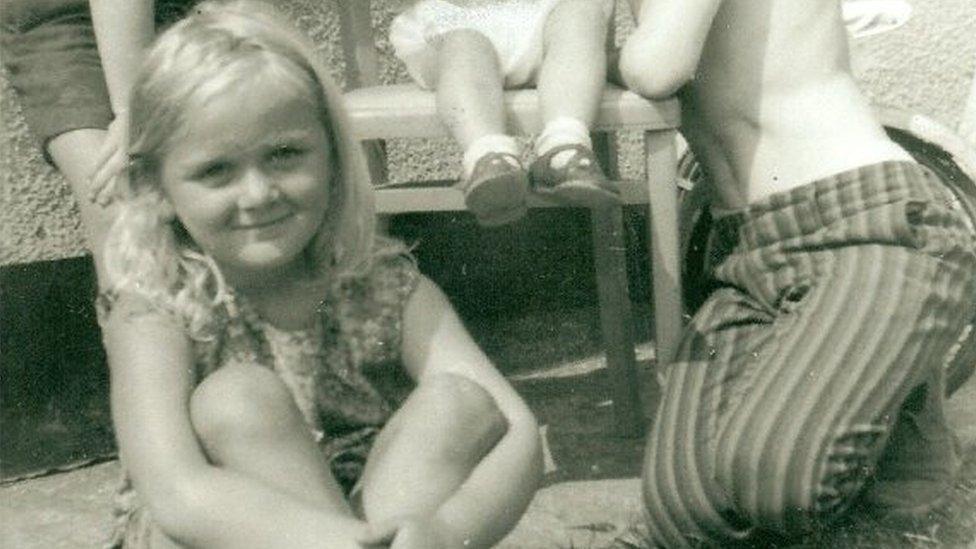

Hayley Kemp pictured with her siblings before she was sent to a residential care home

My mum got lung cancer when I was five.

One of my memories is of her with a beehive haircut and smoking a Woodbine cigarette.

I was the youngest girl of seven children and after she died we managed for a while with my father as a single parent.

Then Dad got involved with a woman called Peggy who became our stepmum and she came to live with us and her two daughters.

But she was really cruel. I wasn't allowed in the same room as her. I wasn't allowed to talk to her and she used to beat us and starve us.

That was quite obvious because when we used to go to school, neighbours used to be outside and brush our hair and give us biscuits, so we must have looked quite emaciated.

I don't know if it was because I was the doll of the family, but she took an instant dislike to me.

She said I had to go, so my dad took me to a children's home.

'He left without even giving me a cuddle'

He said we were going to the dentist on the bus, and I had no idea where we were because I was only seven.

I was skipping down the road thinking 'these are really nice houses and there's a park nearby'.

It was Parklands Children's Home but I didn't know that then. I just thought 'this is a nice dentist'.

These two women came out and he went in with them and I was told to sit on a chair.

And then Dad came out and said 'wait there while I go to the bathroom'.

Then the two women came out and got me and that was it. I was living there. He just left.

There was no cuddle or anything.

I just think my dad was quite a weak man, really, because he would give up his children for somebody who obviously had serious mental health issues.

'I thought I'd died and gone to heaven'

The gateposts are all that remains of Parklands

In a sense I was completely displaced. I had nothing with me, but they went to this big cupboard and picked out these clothes for me.

For me, I'd gone to somewhere lovely. It was like I was on holiday.

All the staff were 'aunties' and 'uncles' and there was so much food and so much fun and lots of other kids.

Honestly, I thought I'd died and gone to heaven.

What I loved was that every Saturday morning they took us out, to the zoo, to the cinema.

And on Sundays we went to Sunday school and came back and had a roast.

You hear that children's homes are awful places - I always want to say there is another side to that story.

You don't hear about the people who had a nice time there, but it was a real refuge and sanctuary for me. I was safe.

'I slept in a cell'

Hayley, right, ran away as a teenager

I was in Parklands for seven or eight months, then they brought some foster parents to see me who had a daughter and I eventually went to live with them.

I found it really difficult to go from lots of children and a really busy house to just having a room by myself, so I found it really difficult and felt quite isolated and lonely.

I live in a house share now and I don't think it's coincidental. I like house shares, I like people around.

In my teenage years I started running away a lot. I would go and stay with my sister and brother who were now married and had their own families.

I spent the odd night in children's homes, but they didn't have space for me so I'd be one night here and one night there.

Then they took me to a borstal (a young offenders institution) in Bristol even though I'd never been arrested and I'd never been to court or charged with anything.

It was in the days of the short, sharp shock treatment, so it was really tough.

It was a cell where we slept.

I was there for a couple of weeks until social services came to get me. I think someone must have kicked off that I was in a borstal.

'I got to know all the sex workers'

Hayley in the house she shared with sex workers in Emma Place, Plymouth

They put me in a bed and breakfast where I had to share a bed with a woman I'd never met before.

I really liked her. She was only 19 but to me, at 15, she seemed really grown up.

She was a sex worker. She used to call herself Judy Teen after the Steve Harley song.

She used to say 'I'm going out to work now Hayley' and meet me after work and she would take me to bars.

But she would never encourage me to do sex work or anything.

It all kind of went wrong because there was a guy there who threatened me and the police turned up.

Social services realised they shouldn't have put me there, with these older men who were trying to get us drunk, so they moved me to Emma Place.

It was a thriving red-light district then and every time I went out - I was 15 then with long blonde hair - I used to get people coming up all the time.

I got to know all the sex workers. I was lucky because I was a babysitter for them.

But when I look at someone who's on drugs or a sex worker I wonder how didn't I end up like that.

'I met my father for a drink'

Moorhaven on Dartmoor, the institution where Hayley was taken after having a breakdown

I have one daughter who is 37 now.

When she was aged five I had a nervous breakdown and they think it was because she had reached the age at which things started to go wrong in my life.

I ended up in an institution [Moorhaven on Dartmoor] for a couple of months.

When I was in my 30s I had heard from someone that my father wanted to see us all, so I decided to go and see him.

I spoke to him and we met and had a drink together and I just decided I had nothing in common with him and I didn't like him as a person, and I had no respect for him.

I had managed so long without him I didn't really feel like he would be a positive influence in my life so I just decided not to see him again.

'I empathise with people who've been displaced'

Hayley now works with Iraqi and Palestinian refugees

You may also like:

I was working in the private sector as a quality assurance manager and when I was 40 I thought 'I just don't want to do this - this is not what I want to be doing.'

I always call it my mid-life crisis.

I gave it all up and went to work voluntarily with refugees.

When I was in foster care we had Uganda-Asian refugees living in a centre nearby.

We collected blankets and jumpers and clothes for the families and I remember thinking they were the most courageous people I had ever seen.

They had escaped all this horror and here they were making this new life.

I don't think that ever left me about how courageous they were.

And I think it's because I just have this empathy with people who have been displaced.

They don't know when they're going to see their family, they don't know where they're going to end up.

'I was fortunate to have the childhood I had'

Building shelters at the Calais refugee camp

I do a lot of work with asylum seekers and refugees and in refugee camps in Iraq.

When people grow up in a stable home and they have got this unconditional love, they learn all those things that people take for granted.

So they grow up and they watch their mother cooking, or they learn about budgeting, or they see them sewing or ironing.

I didn't have a clue how to do any of that.

But the childhood I had has given me an empathy with people that I think I wouldn't necessarily otherwise have.

I get to work with the most amazing people and they let me into their lives, and that is a massive privilege.

It also gives you a resilience and strength that you can't learn because no matter how bad something is, it's not permanent. Things do get better.

So I'm very fortunate to have had the childhood that I had, because no-one can teach you that. You have to really feel it.

It's given me a real sense of courage and resilience and determination and I'm very lucky to have that.

As told to Jonathan Morris

- Published2 April 2019