From nuclear to nature: Dismantling an atomic site

- Published

Cecil Trent's family had to move out when their rented farm was taken over by the Atomic Energy Establishment

Cecil Trent remembers Winfrith when it was fields - his father was a tenant farmer and grazed cattle on the heathland in Dorset.

But in the late 1950s the family had to leave because the government wanted the land for atomic energy research.

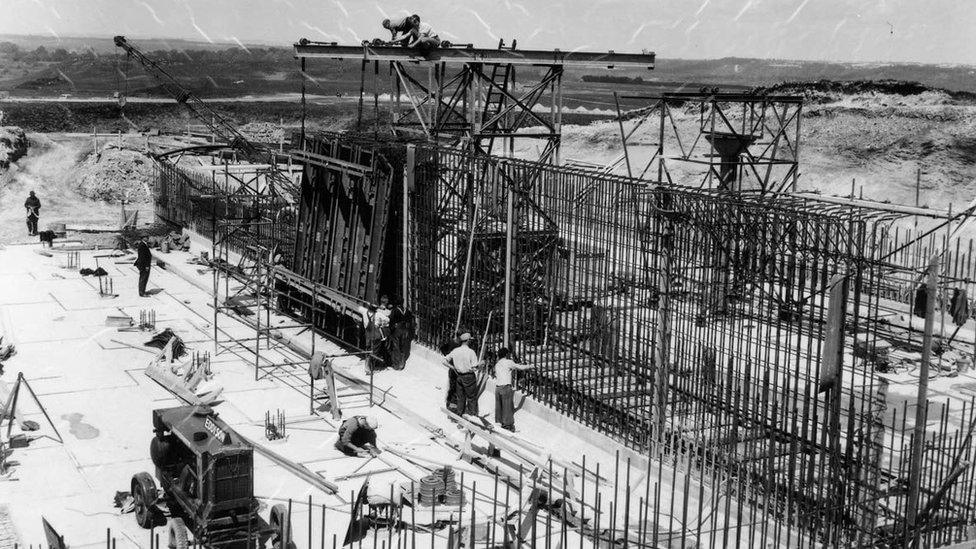

In the years that followed, nine experimental reactors were built where pioneering research was carried out.

Nowadays, the ground-breaking work is focussed on returning the site to heathland - something Mr Trent never believed he would see.

Blacknoll Hill, overlooking the power station, was hollowed out to make a reservoir

In the 1950s after a long wait for a tenancy on the Weld Estate, the Trent family began rearing cattle with the hope of setting themselves up as dairy farmers - just as soon as a planned water pipeline was connected.

But the dream was never fulfilled and the pipeline never completed because, unbeknown to them, the land had been requisitioned and their landlord sworn to secrecy.

Mr Trent said: "My father came in one day and said 'where have all the pipes gone?' He chased up the Weld Estate and they just hushed up and couldn't tell him anything, even though they knew what it was all about.

"They [the Atomic Energy Establishment] eventually took over the farm and we had to get out."

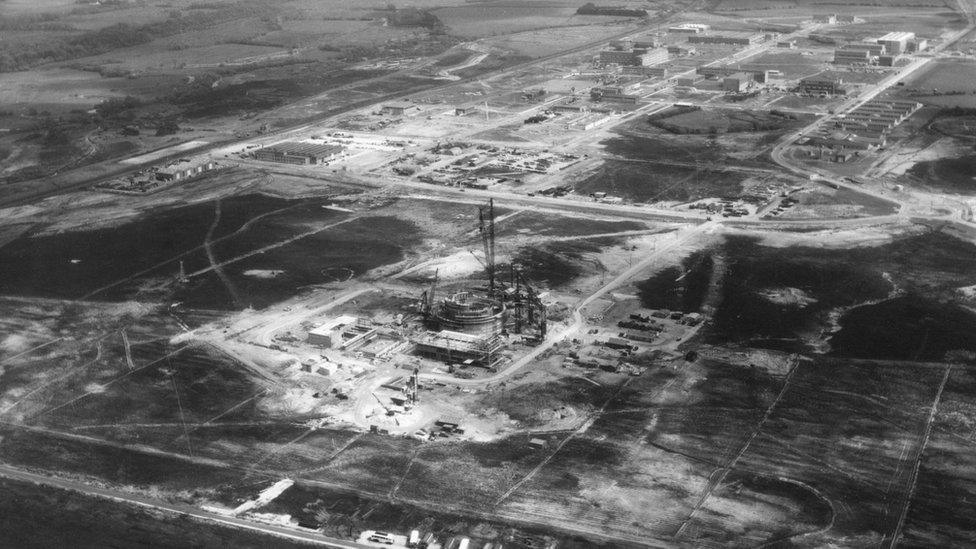

This 1961 aerial photo, facing north east, shows much of the site still under construction with a railway line that runs along the northern perimeter on the left side of the picture

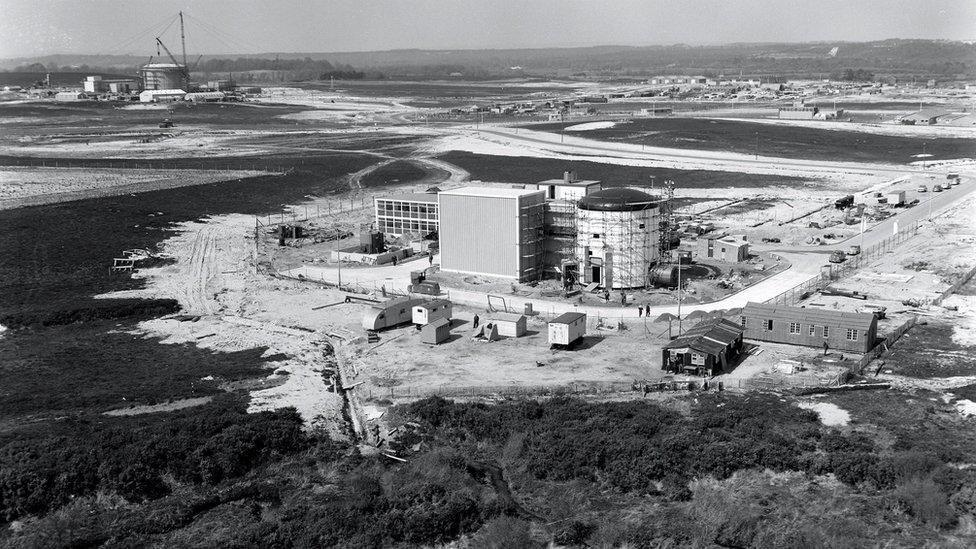

This south west-facing photo was taken in 2014 when decommissioning was well under way with the railway line seen at the bottom of the picture

In the months and years that followed, Mr Trent saw Blacknoll Hill - where he played as a child - being hollowed out and a reservoir built which was then covered back over.

He said: "I remember looking down... and the diggers at the bottom looked like dinky toys. If you go over the top now, you wouldn't know what was underneath - there are still manhole covers but they are hidden in the bushes.

"I can't go to Winfrith without going up that hill. When the heather is out it really is a sight to see. I'll carry on going up that hill until I die."

In 1957, having just received his National Service papers, Mr Trent left to join the Army and his father, who already had a job on the railway, gave up his dairy farming dream.

Work at Winfrith supported research at Harwell in Oxfordshire and, during its heyday, there were 2,000 people working there, building and testing reactor designs and testing materials inside them.

In its heyday there were 2,000 people working at Winfrith, carrying out pioneering research

Zebra was one of nine experimental reactors to be built at Winfrith

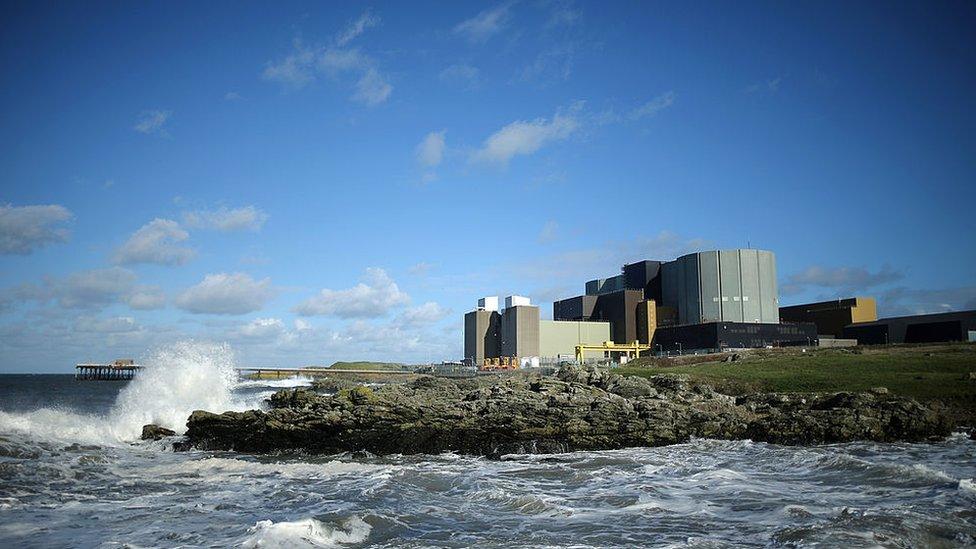

It is now six decades since the Trent's farm was wiped from the map. Now work is well under way to remove all trace of Winfrith's nuclear legacy too.

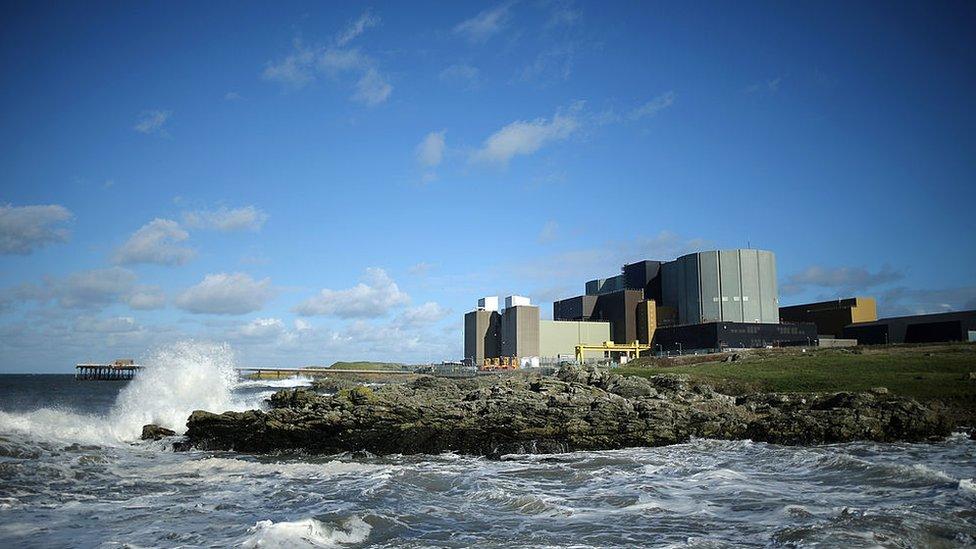

Since its closure in 1990, seven reactors - Zenith, Nero, Juno, Hector, Nestor, Dimple and Zebra - have been removed, along with cooling towers and other buildings, but the most complex tasks remain - to dismantle the enormous water-cooled reactor called SGHWR and a prototype gas-cooled reactor called Dragon.

Engineers have stripped out miles of steel pipework surrounding the SGHWR core - the only one of the nine reactors to supply the National Grid - so new structures can be built to seal it off and allow robots to cut it to pieces.

No-one will be able to access the reactor once the robots begin dismantling it, so full-scale models have been built in a nearby building to plan how the techniques would work.

After 20 years of operation, Zebra was shut down in 1983 and demolished in 2005

Winfrith closure director Michael Dunnett said: "There is probably nothing on earth as well planned as this."

New technology is being developed to facilitate the decommissioning, while existing technologies such as production line robots and hydraulic bridge jacks are being adapted to carry out work in the most radioactive areas.

Equally complex systems have been developed to decommission Dragon, which ceased operation in 1975, such as a bespoke robotic "laser snake", capable of cutting into the structure.

The active plant around the reactor core has already been stripped out and removal of the core is due to begin in 2020.

The process is so well planned that site operator Magnox predict it will return the site to heathland by 2023.

Despite the careful planning, the decommissioning project has thrown up some surprises.

Mr Trent remembers the reservoir being built at Blacknoll Hill, where he played as a child

Mr Dunnett said: "One of the challenges of decommissioning a research and development site is that not everything is quite as you would expect so from time to time you will find wastes or you might find parts of the decommissioning process that weren't there in the drawings."

Other aspects of the project remain to be decided, including the future of a pipeline built to take low-level waste out to sea. The pipe, which passes under numerous landowners' areas, including a Ministry of Defence live firing range, may be cleaned and left in place instead of being removed.

When complete, Winfrith will be the first nuclear site in the UK to be fully decommissioned, meaning its nuclear licence will eventually be removed.

Mr Trent said: "When you see something like that going up, you think it's going to be there forever. I never imagined in my lifetime that it would be cleared away.

"But I think they did me a favour - it was my father who wanted the farm and I got to join the Army as a trainee mechanic."

- Published11 October 2017

- Published1 April 2017

- Published27 March 2017

- Published18 January 2016

- Published21 May 2015