Hardest sell: Nuclear waste needs good home

- Published

Many people's idea of nuclear waste is neglected barrels dripping glowing goo but the truth is inevitably more complex - and surprising

What would it take for you to accept nuclear waste in your backyard? The country has created quite a bit of the stuff and the government is searching for someone willing to take it.

Steadily produced since the end of World War Two, the question of what to do with the nuclear waste from civil, military, medical and scientific uses has been causing equal measures of fear and frustration for decades. With a new generation of nuclear power stations, external on the way, a fresh search is under way for a community ready to take on the challenge.

Campaigner Eddie Martin says: "It's very worrying, scary even. They have been looking for somewhere to put this material for decades and it keeps coming back to Cumbria."

In the rush for nuclear power, the long term dangers were not fully understood

Dr John Roberts, from University of Manchester's School of Physics and Astronomy, says: "Everything around us, including us, is radioactive to some extent. Your body is evolved to cope with a lot of this.

"Different materials emit different types of radiation, but also at different rates. This is the half-life - which is the time it takes for the level of radioactive to fall to half of its initial value.

"A short half-life means lots of radiation emitted but it is expended quickly. Some isotopes have a half-life of just days, or even less than a second, others can last tens of thousands of years but emit very little energy.

Radiation - what is it?

Radio waves, the ultraviolet in sunshine and the visible light needed to see them are related to x-rays and gamma radiation

Radiation is transmission of energy in the form of waves or particles,

Some forms part of the electro-magnetic spectrum, which starts with radio waves, then microwaves, infra-red, visible light and ultraviolet light (UV) to X-rays and beyond.

Other types of radiation are emitted as subatomic particles.

When either the waves (beyond UV) or particles are powerful enough to start damaging the DNA of living cells, it is known as ionising radiation.

Ionising radiation itself is broken down into different types - known as alpha, beta and gamma.

Roughly speaking, alpha radiation is big and slow, meaning it can do a lot of damage to cells but cannot travel far and is easily stopped - by skin for example.

Gamma, small and fast, can pass through skin, cells and even thin metal but does relatively less harm, so a larger dose can be tolerated. Beta sits between these two.

Radiation is measured differently depending on whether you are looking at what is emitted (usually expressed in becquerels, external) or its effect on the body (commonly counted in sieverts, external).

"Something like Caesium 137, a product of nuclear reactors, has a half-life of 30 years and puts out a lot of gamma radiation, so is one of the more problematic isotopes.

"The mix of materials in nuclear waste means it could possibly need to be isolated for thousands of years.

"The radiation dose any person might get from a source depends primarily on the energy of the source, the length of exposure, the distance, which part of them the body is exposed, what they are wearing and very importantly whether it is ingested or inhaled."

Nuclear power stations have been built in 31 countries, external but only a handful, including Finland, external, Sweden, France and the US have started building permanent storage facilities.

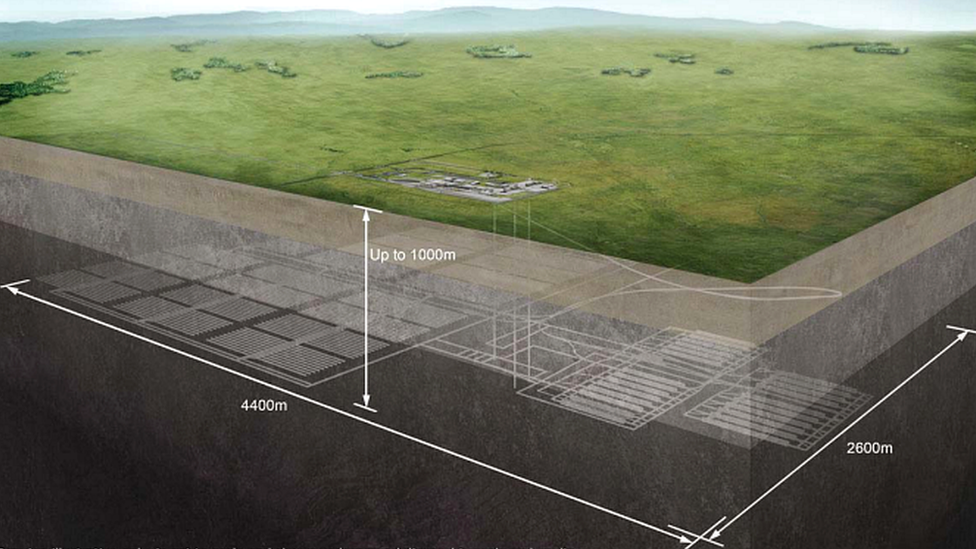

All of these are purpose-built caves hundreds of metres below ground, known as a Geological Disposal Facility (GDF). Once the waste is treated and sealed inside containers, it is stacked in the caverns. GDFs are expected to remain secure for thousands of years.

Dr Robert says GDFs or deep boreholes are two possible options for the disposal of radioactive waste but there are still challenges to overcome, particularly in predicting their behaviour over hundreds or thousands of years.

"While there are natural examples of radiation being contained - think of the mines where uranium for nuclear fuel has been sat happily for millennia - the mix of isotopes in radioactive waste is much more complex so we need to know how the nuclear waste interacts with its storage material, be it glass, concrete or metal.

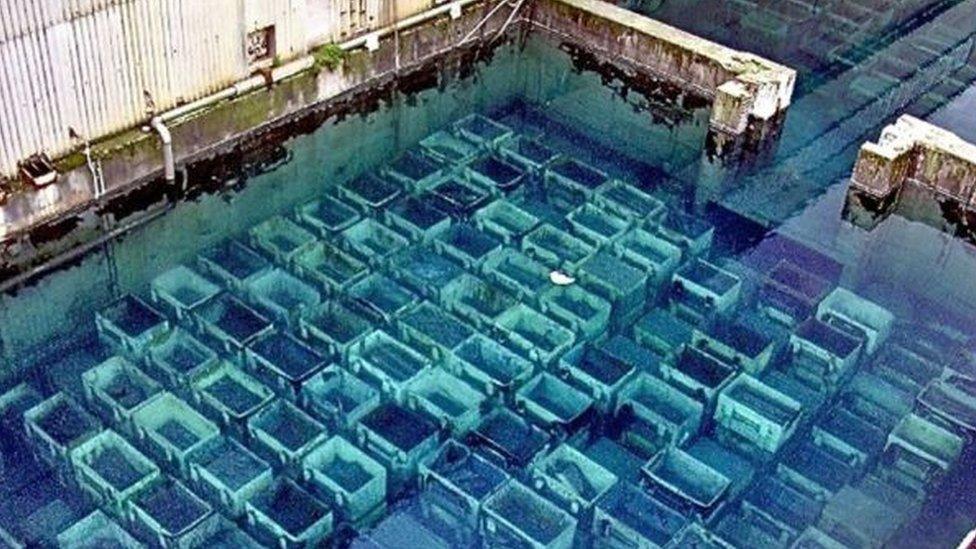

Crumbling storage ponds, hastily built in the 1950s, are now being expensively cleared and waste moved to new, temporary storage

"And then, it best to put the containers in granite, clay or salt? Other countries are trying different options.

"But this is basically an engineering project like no other. Its timescale will dwarf the oldest cathedrals.

"We also need to ensure we can guarantee the records will be kept of what is down there and where. It has to last for hundreds of years and how many records have we lost since the Tudors? Or the Romans?"

So, from the carefree days of dumping it in the Irish Sea there dawned a realisation the predicted 650,000 m3 of nuclear waste needed a more permanent solution. So where are we in the process? And how did we get here?

Nuclear energy production has been dogged by fears of accidents and leaks - several spills have been recorded

Pete Wilkinson, environmental campaigner and member of the committee which in 2006 officially recommended underground storage, explains: "This process really started in 1976 when a report said there should be no more nuclear power without a method of disposing of the waste.

"In the 1980s there were various attempts to impose disposal on communities in Bedfordshire and what was then Cleveland but opposition was loud and well co-ordinated and people would not put up with it.

"An attempt to build an underground 'laboratory' at Sellafield in Cumbria was thrown out in 1997, with the government saying proposals represented bad science and poor stakeholder engagement.

"In 2003 they set up the Committee for Radioactive Waste Management (CoRWM) to come up with the definitive solution."

He added: "As well as recommending the deep geological solution, it came up with the idea of volunteerism - that a community had to agree to host the facility.

"But I think they have underestimated people's antipathy for having radioactive waste in their backyard.

"The first attempts to reach out to the public were inadequate - lots of talk about impact on tourism and how many jobs it would bring.

When waste storage in Cumbria was discussed in the past, it provoked fierce opposition and dozens of protests

"But people are most concerned about the radioactivity. Is it safe? And that was not addressed at all."

This "first attempt" got as far as two Cumbrian borough councils, Copeland and Allerdale, both next to Sellafield nuclear facility, showing interest.

After much local protest, permission to proceed with detailed geological surveys was refused by Cumbria County Council in January 2013.

Dusting itself off, the government restarted the process, in the meantime passing legislation, external that left any final decision about a location in the hands of ministers.

This summer saw the launch of a National Geological Screening Guidance consultation, external, a review of existing information about the suitability of sites across England and Wales, with councils and organisations invited to comment.

Eddie Martin, a former leader of Cumbria County Council and founder of the Cumbria Trust, said: "Sellafield has been filling up with other sites' waste and is it any surprise the last search ended up here?

"It's not for any pragmatic or geological reason, it's socio-economic expediency. Part of this county already relies on the nuclear industry, so it's more likely to accept some more.

Nuclear energy provides about 20% of the UK's energy and is becoming more important as coal-fired power stations close

"On top of that there are some cash-strapped local councils in this part of the world and the financial perks offered will seem appealing in the short term.

"The only thing which stopped it last time was the balance of local interest and scrutiny that the county council brought.

"Now they are running the same search again, which will come up with the same result, only this time they have legislation in place to make sure the county council can't stop it. It's an abuse of democracy.

"Cumbria is not the right place for this facility. First of all there is the sheer strain of building the thing. A 16-tonne lorry every three minutes for 20 years. On our small roads.

"Then the geology is wrong. Granite rocks are too fractured, they are too prone to water running through from the mountains and any number of studies back this up.

"This waste can devastate for thousands of years. It has to go somewhere but this is the wrong place. It is too important just to take the easy option."

A handful of other countries have built experimental underground "laboratories" to test storage ideas

A spokesman for Copeland Borough Council said: "The government has tentatively begun a new, national process to seek volunteers to engage in the process of considering whether those areas would wish to host a GDF.

"This would involve some preliminary work on geology (desk based) similar to that which has already taken place in west Cumbria.

"Copeland, at present, have not and have no current plans to volunteer to host a GDF, this would be a matter for full council to consider informed by our communities.

"However, we continue to follow the process, as 80% of the UK's higher activity nuclear wastes continue to be stored on the Sellafield site."

Winfrith is an example of modern temporary storage for intermediate nuclear waste, with the material sealed in concrete blocks and constantly monitored

But Cumbria is not alone. Previous studies, external have shown a dozen areas that might - under further scrutiny - prove suitable.

One of these is Stanford on the Norfolk/Suffolk border, not far from Thetford. One expert says, external it "fits the international criteria very well indeed".

The area in and around the army base is about as empty as you can get in lowland England, which is likely to increase interest.

But Joan Girling, who campaigns for improved safety at Suffolk's Sizewell nuclear power plant, is uncompromising.

"By the time it is decommissioned, Sizewell will have been a nuclear site for 100 years. The area has done its bit.

"Just think of the issues bringing it here, it would be a nightmare. Imagine transporting all that waste from Sellafield, across the country, presumably by rail, then what?

One site previously deemed suitable, and usefully empty, is the army's Stanford Training Area on the Norfolk/Suffolk border

"Lorries laden with 130-ton waste flasks rumbling up and down country lanes for years on end.

"And no-one has any idea if it - moving it, the construction, the hundreds of years of waiting - is really safe."

Breckland Council, which covers the area, said it referred the issue to the county council. In turn Norfolk County Council said it did not respond to the consultation as it believed no community was interested.

But not everyone treats nuclear waste like it was, well, nuclear waste. Devonport naval base in Plymouth is home to 12 old nuclear submarines, eight with fuel still on board.

In 1993 the city threw a street party when it secured long-term contracts to keep the vessels. To many the base means jobs and security.

Along with working submarines, Devonport hosts a number of redundant vessels

The Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA) has overall responsibility, and a £3.3bn annual budget, to clean up the UK's radioactive legacy.

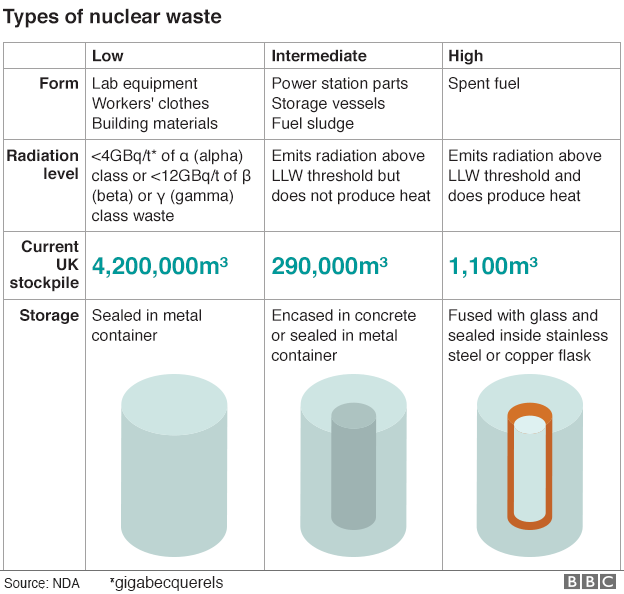

While there is currently about 292,000 cubic metres of the most radioactive waste in its raw state, the volume to be stored, when future production, treatment and containment are factored in, is about 650,000 cubic metres.

The part of the NDA tasked with finding somewhere to put it all is called Radioactive Waste Management (RWM) Ltd.

Its chief scientific adviser, Prof Cherry Tweed, is clear in her belief they are on the right track.

She says: "There is a very strong international consensus that geological disposal is the safest and most practicable solution for these wastes and that it is technically feasible.

The GDF would be an immense undertaking, even when issues over safe nuclear waste storage have been resolved

"We as a responsible developer would only want to go ahead and build a facility provided we are confident it would be safe and it won't just be on our say so, And there is the further reassurance for the public that all the safety arguments will be scrutinised by the independent nuclear regulators before they issue the necessary permits."

The GDF will certainly be an awesome undertaking. It is expected the surface buildings alone will cover 1km sq. The underground tunnels will stretch for 10-20 km sq. On a Cumbria scale, that is bigger than Carlisle.

It will take decades to build and predicted costs are almost unguessable - but most estimates agree on billions of pounds.

But before these technical issues are tested, RWM must do something that has eluded the authorities for decades. Find a volunteer community.

This has not been made an easier by the US disposal site being temporarily shut down, external after leaks and continued doubts, external over GDF designs.

Prof Tweed believes they will succeed due to lessons learnt from earlier failures.

The NDA and RWM have already set out a timetable for how they would like to see the new search progress

She says: "Stakeholders told government what they wanted to know was they wanted more information upfront, on the geology in their locality and on the way in which they would be involved and represented through the process and on the investment package.

"And we have been working very closely with the American authorities to make sure we understand the causes of that accident and that we learn from it."

She also rejected the ideas the political pressures would inevitably lead again to a site in Cumbria, or a geologically unsuitable site would be selected because a financially hard-pressed community would take it.

"There is no plan to go back to Cumbria, or anywhere else in the country. Although we haven't started the formal search we have had positive responses from not just Cumbria but from many places across the country and we have this opportunity over the next 12-18 months to build awareness of what we are doing.

"If at any stage in the process we found something that told us a GDF would not be safe in that particular locality, we would walk away. However keen the community are, safety is paramount."

She adds: "We as the generation who have generated the waste have a moral and ethical responsibility to put a solution in place."

BBC Inside Out South West's investigation into Devonport will be broadcast at 19:30 BST on 18 January

- Published21 October 2015

- Published12 October 2015

- Published5 October 2015

- Published13 July 2015

- Published27 February 2015

- Published4 March 2014