Benjamin Jesty: The unsung hero of vaccination

- Published

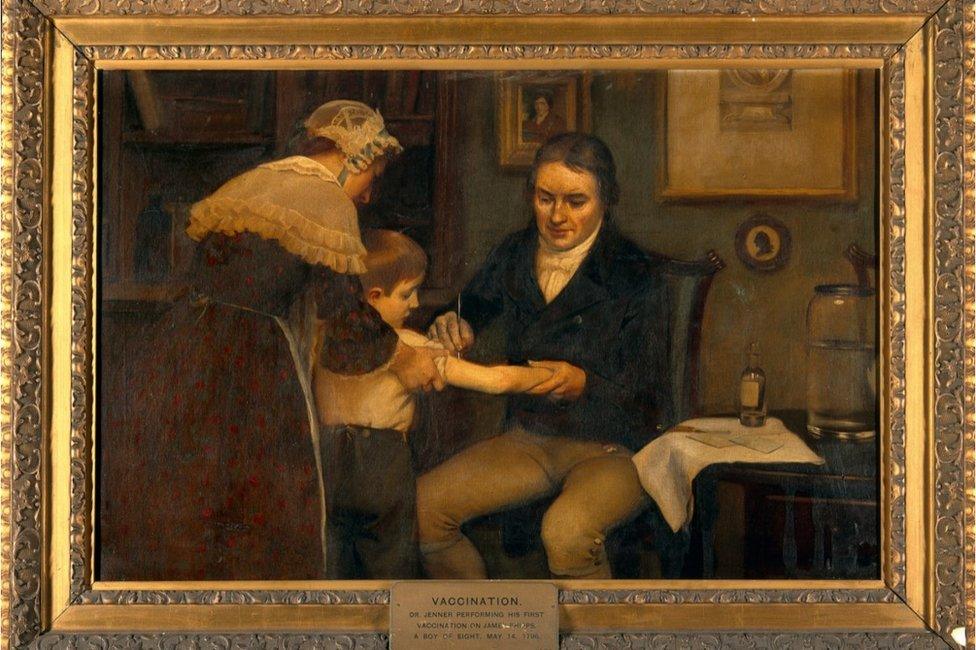

Edward Jenner is credited with developing the first vaccine

More than 250 years before the coronavirus pandemic, another deadly virus - smallpox - was sweeping Europe.

The epidemic led to the development of the first vaccine - a medical milestone credited to Gloucestershire physician Edward Jenner.

But, while Jenner became rich and famous for his discovery, the technique had been pioneered more than two decades earlier by a Dorset dairy farmer whose social status meant he never received the recognition he deserved.

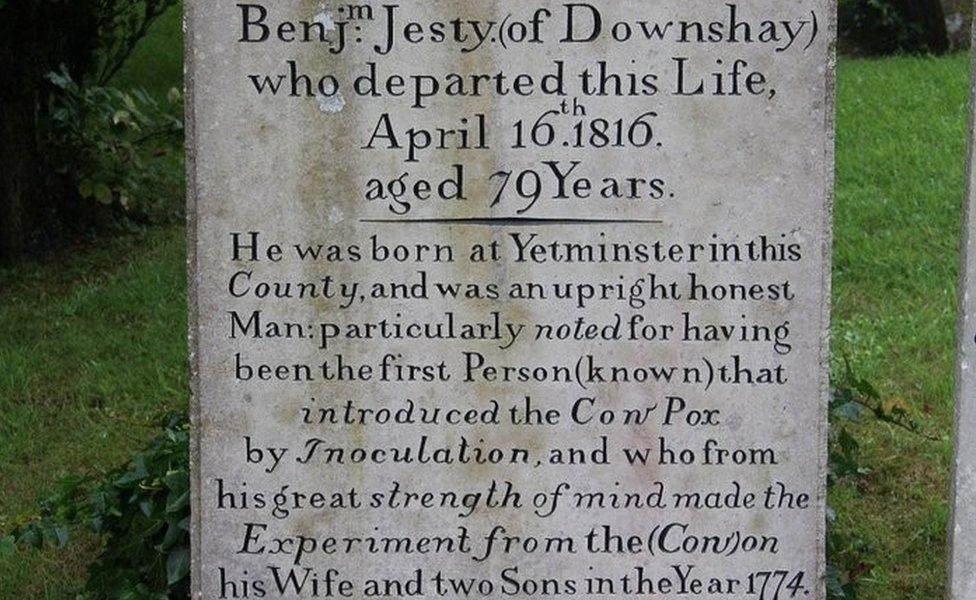

The gravestone in Worth Matravers makes reference to Jesty's vaccine

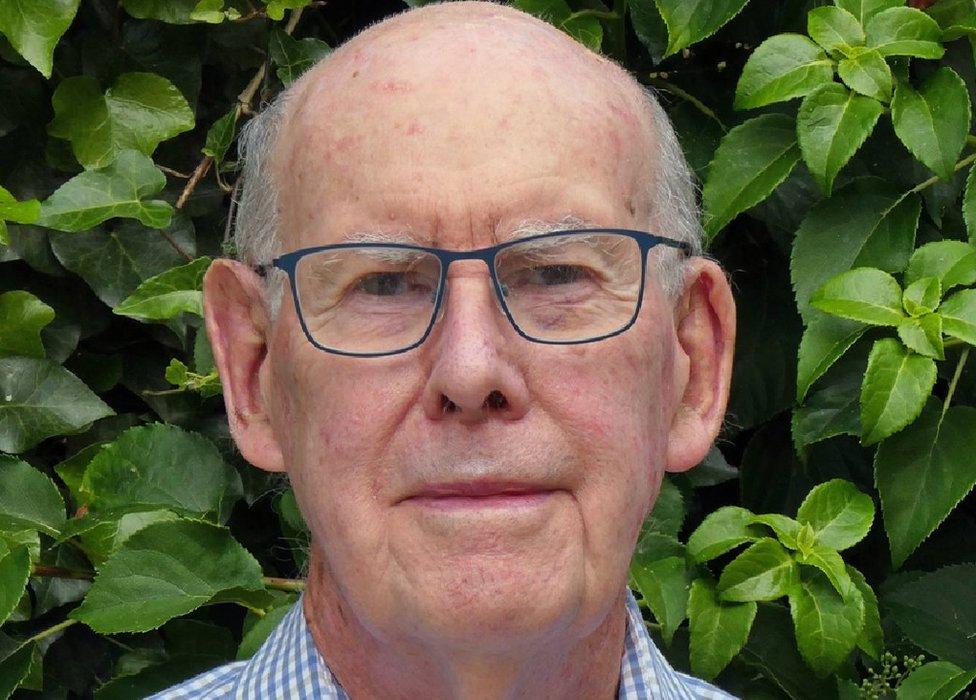

Fast-forward to 1985 when microbiologist Patrick Pead, on holiday in Dorset, picked up a booklet in a Worth Matravers village shop entitled Benjamin Jesty: The First Vaccinator.

"I thought 'that's not right, it was Edward Jenner'," said Mr Pead.

"We went to the churchyard and saw his tombstone and that day changed my life."

In the years that followed, Mr Pead turned detective, piecing together the little that was known about Jesty and tracking down new evidence, including the only portrait of the farmer which was believed lost for more than a century but had found its way to the other side of the world.

Jesty's story began in 1774, when the farmer from Yetminster deliberately infected his family with cowpox in a bid to protect them from the deadly smallpox virus.

Smallpox was the leading cause of death in the 18th century. Most people became infected during their lifetimes, and about 30% of those infected died.

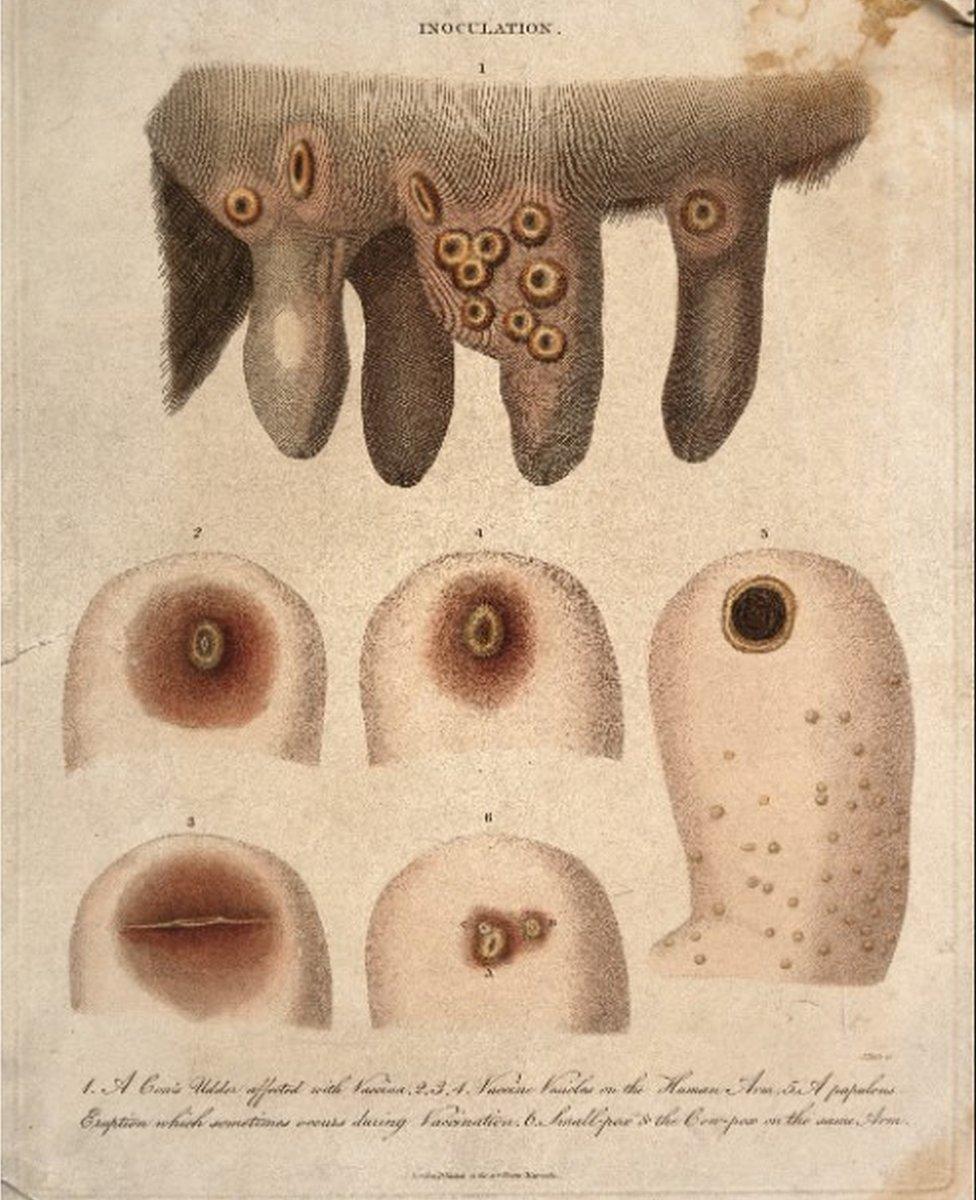

Jesty had contracted cowpox in his youth and knew that milkmaids seemed, somehow, to be immune from the more virulent human disease.

Using pus taken from lesions on a cow's udder, he used a stocking needle to scratch the infected material into the skin of his wife and two sons.

The Jesty family lived in Yetminster, in west Dorset

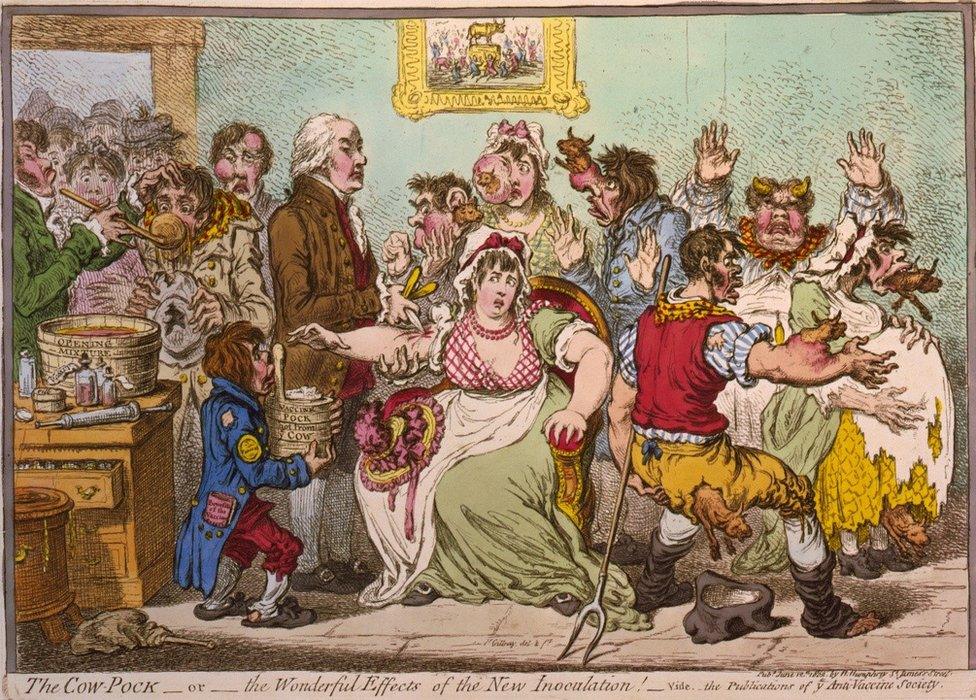

But his wife became very ill and, although she eventually recovered, Jesty was vilified.

"The last trial for witchcraft had been less than 40 years earlier," said Mr Pead.

"Jesty was reviled, people were suspicious.

"In those days, everybody would go to church on Sunday and the human body was sacred but here was a guy taking something from a beast and poking it into a human body."

Jesty's experiment would later be proved successful when attempts to infect his sons indicated they were immune to smallpox.

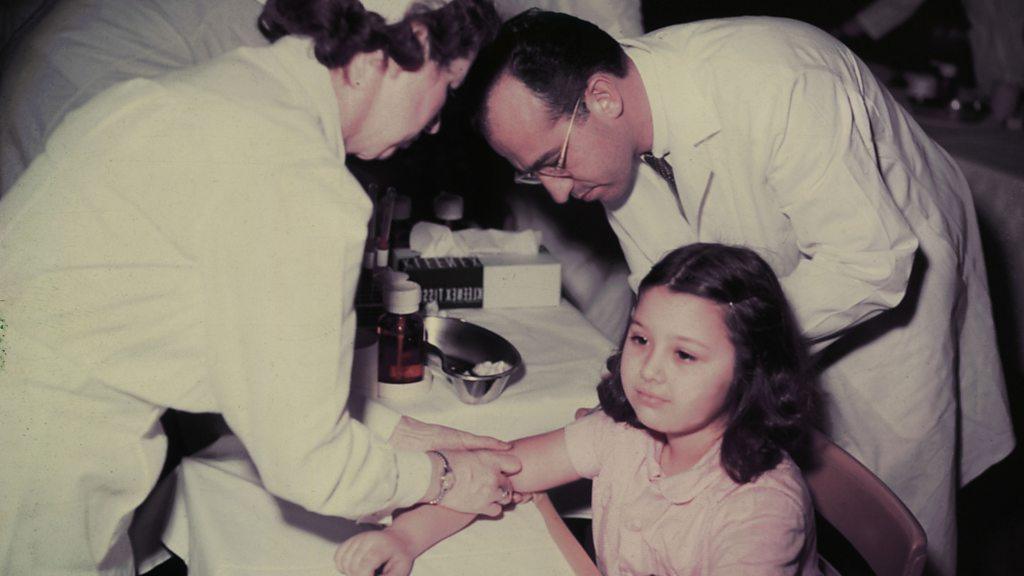

In 1796, Edward Jenner, who is believed to have heard of Jesty's exploits through his dining club, carried out a similar procedure on an eight-year-old boy but his findings were rejected by the Royal Society.

An 1811 engraving shows an infected cow's udder and a human arm

By 1798 he had conducted experiments on 23 children and, following support from his colleagues and the king, was awarded vast sums by parliament - first £10,000 in 1802, then a further £20,000 in 1807.

But Jesty's contribution did not pass unnoticed, with doctors and clergy calling for him also to be recognised.

In 1805, their lobbying led the Vaccine Pock Institute in London to quiz Jesty about his experiment and he was presented with a scroll and gold lancets.

A prominent artist - Michael William Sharp - was also commissioned to paint his portrait but, despite the gesture, Jenner's well-connected supporters won the day and Jesty looked set to remain a footnote in medical history.

Satirists depicted recipients of the smallpox vaccine growing cow parts

Mr Pead's quest to find Jesty's portrait led him to the archives of the Eldridge Pope Brewery in Dorchester - the painting had passed to the Pope family through marriage but had since disappeared.

After making inquiries he was given the telephone number of a Pope family descendant in South Africa.

He said: "I rang them straight away - it was about 10 o'clock at night. They said 'it's hanging here above the fireplace in the family home.'"

The owner said he wanted to sell the painting and was keen for it to return to England.

Patrick Pead said researching Jesty had been a "labour of love for many years"

In 2006, the Wellcome Trust in London agreed to acquire the portrait but its journey back to the UK was "a nightmare" according to research development specialist William Schupbach.

"The cost of getting it to the UK was considerable compared with the actual cost of the purchase," he said.

"It was on a farm on a huge estate in the Eastern Cape so we had to identify art handlers who had to drive their lorry hundreds of miles to get to this farm house.

"We did not know what condition this painting was in - it had been stored in a barn in Dorset before being taken to South Africa.

"And because South Africa is outside the EU there were import regulations."

After a restoration project lasting two years, the painting finally went on public display - first in Dorset Museum in Dorchester, then at the Wellcome Collection galleries.

Since then, interest in Jesty's story has grown, Mr Pead has written books and articles, given hundreds of talks and was awarded a Fellowship of The Historical Association for his research.

He said: "I'm a scientist working in medicine and I know all of the progress is built on the findings of others.

"Vaccination wasn't plucked out of the air by Benjamin Jesty or by Edward Jenner, it was built on out of what went before - that's why Jesty does deserve recognition."

Follow BBC South on Facebook, external, Twitter, external, or Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to south.newsonline@bbc.co.uk, external.

Related topics

- Published4 March 2022

- Published12 March 2020

- Published28 December 2019