Migrant barge: Portland is a dumping ground, residents say

- Published

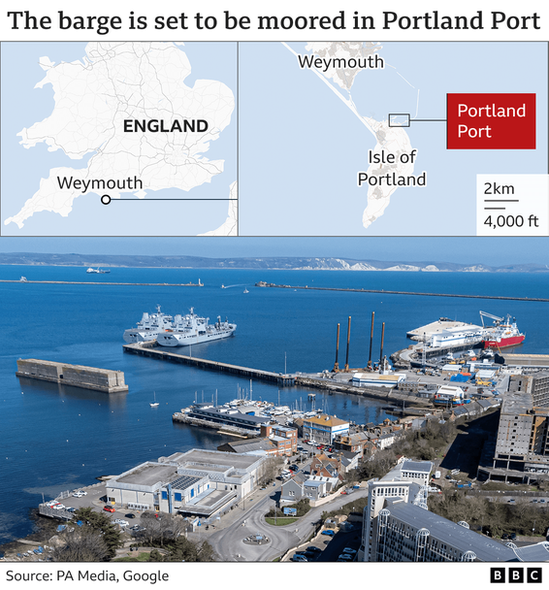

Portland Port was selected by the Home Office as a site for a migrant barge

Portland in Dorset will be the first place in the country to house asylum seekers on a floating accommodation barge.

The Bibby Stockholm was moved out of dry dock in Falmouth, Cornwall, last week after a refit to accommodate up to 500 single men for at least the next 18 months. It is expected to be towed to Portland in the coming days.

The BBC's west of England correspondent Dan Johnson has been to see how people on the island are reacting to this new and controversial government policy.

"They think Portland's a dumping ground," Charles Richards says.

"They've dumped it here because they think we don't matter and they think we won't make a fuss. Portland has been treated with contempt."

The 78-year-old has lived his entire life on the island.

We settle on his garden wall overlooking the port where he worked for the Ministry of Defence (MoD), packing missiles. It seems everyone here is connected to the military or the prison service.

"Portland has always been exploited," he continues.

Portlander Charles Richards believes Portland is thought of as a "dumping ground"

"The stone firms exploited the land and dug great holes in it. The MoD exploited it to make fortifications and naval bases. The government used it for prisoners. We've had people dumped on us for a long time."

Portland is one of those places on the edge, an extremity of England dangling from the Dorset coast by the fine thread of Chesil beach.

I notice a sign in a neighbour's window: "Keep Portland weird."

It only takes 10 minutes to drive from end to end, but it is not insular and there's a sense this rugged, weather-beaten landscape bears more than its fair share of our national weight.

Between the quarries that sent bright, white stone to face Buckingham Palace and St Paul's Cathedral sits His Majesty's Prison The Verne, home to 580 sex offenders - recently reported to include Gary Glitter. Then there's HMP Portland with another 500 inmates.

Completing an unholy trinity of incarceration used to be the prison ship HMP Weare - a "temporary measure" to ease overcrowding that lasted eight years. Its 400 prisoners put the proportion of the island's population held behind bars then at 11%.

Now another barge is heading for the same spot. It is the flagship of the government's latest plan to "stop the boats" and deter dangerous channel crossings.

Dorset Council is receiving £1.7m over the planned 18-month duration of the vessel's stay in the port - based on £3,500 per bed space, with a further £377,000 available to fund support and activities its residents.

Although Councillor Laura Beddow says the authority had "serious concerns" and believes Portland is the wrong place to site a barge, she admits: "We are in a position where we have statutory services we must provide."

The Home Office claims the vessel will ease the pressure on the asylum system, external.

However, it has amassed opposition from a wide range of voices, here and beyond, and there is still hope a legal challenge could be mounted.

The Bibby Stockholm will accommodate 500 single men

"People are worried about these young blokes," Mr Richards says.

"What are they going to be doing? Wandering about? We don't know what they'll get up to, where they're going to go, or who they're going to mix with. Are they going to be involved in drug dealing? It's something we don't need."

I hear the same questions between the clanking bowls on the green at Victoria Gardens.

"Yes, they have to go somewhere," Kathy Smith agrees.

"But for a barge to come here… our infrastructure on the island is very difficult. We've got one road on, one road off. We have problems getting doctors' appointments as it is - will they get priority?"

The same concerns are echoed on protest banners, amplified in Facebook groups and aired during a fiery public meeting.

Representatives of the town and county councils, the local NHS and Dorset Police face angry residents, joined on a temperamental video link by officials from the Home Office.

The barge has previously been used to house homeless people, asylum seekers and offshore workers

One lady fears for the safety of women and girls. Another worries about conditions for those on board. There are questions about mental health support for the migrants, their spiritual wellbeing and how free they will be to come and go.

Is this really cheaper than using hotels? What about security? And who should be guarded from who?

Some reckon the drab accommodation block will put off tourists. Everyone - local officials included - are enraged by the lack of consultation.

There are not many answers or much detail. The man from the Home Office describes an "emergency situation", saying the asylum seekers have all passed initial assessment and been checked against police and immigration databases.

He talks about devising "activities for those on board that help occupy their time productively". There's derision. "You're a liar and a coward," one man shouts.

Then the discussion turns to the state of Portland's public services. "It can take four weeks to see a doctor," a woman complains. There is no dentist and the pharmacy's overrun, the meeting hears.

Some feel anti-social behaviour is beyond control already - the island has more lighthouses than police officers.

Infrastructure on the island is "very difficult", resident Kathy Smith says

The officials seem stunned. They promise more information and improved services but then they admit that all 500 men will have to be registered with GPs in the area.

It is too much for one chap who bellows: "If we go to our health centre and it is clogged up with asylum seekers there will be a kick back, because we are fed up to the back teeth. You can't even give us proper healthcare now. It's disgusting and you should be ashamed."

In amongst these concerns are hints of prejudice and flashes of racism. Some want to make much broader points.

"These people are not refugees," another man shouts.

"They're not coming from a war-torn country, they are economic migrants."

'We should come first'

Ms Beddow suggests comments about immigration policy need to be directed to the government.

As the chair struggles to wrap up the debate another man shouts one final comment: "Where is your duty of care to us? We should come first."

It is an awkward collision of central policy and local experience. It reveals a powerful sense of a community feeling forgotten, with emotions stirred by the very thing - the barge - designed to reassure voters that asylum seekers are not living in taxpayer-funded luxury.

Back on the bowling green, Tim Munro, a former mayor of Portland, sums it up for me: "We really don't want the nightmare scenario to come true, that we have lots of young men looking for things to do around the island."

I question why his presumption is so negative.

"They can't work," he says. "And clearly they're not going to sit on a boat in Portland Harbour all the time so what are they going to do? I don't know, so I can only imagine the bad things that might happen."

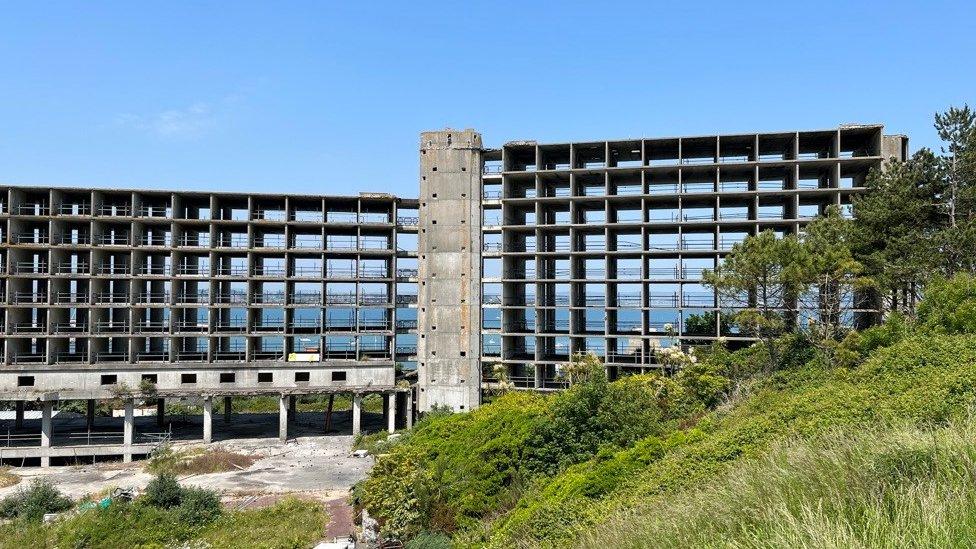

A plan to house 750 asylum seekers at this former Navy block was rejected 20 years ago

Mr Munro reminds me the island accommodated thousands of young men when the Navy ran the port - "boozing and doing what young men do," he says. But he cites longstanding maritime connections and the military police as reassuring counterbalances.

Among the ironies mounting up on the island is the abandoned ruin of a former Navy accommodation block bearing down on us, opposite the port.

A plan to house 750 asylum seekers there was rejected 20 years ago.

I remind Mr Munro of the thousands of visitors during the Olympics, when Portland hosted the sailing.

"Those people shopped in Waitrose, came from Bath, travelled by train, took their rubbish home - they were all very civilised and nice people," he says.

"That's who comes to watch sailing at the Olympics. That's not what we've got now. We hope they'll turn out to be those lovely, nice people that don't impact very much on the local community. The only concern is the unknown, that's all."

Stand Up To Racism is running its own campaign - "Refugees welcome here: No to the prison barge," urging protestors to focus on the policy not the people.

Tim Munro, a former mayor of Portland, says his main concern is "the unknown"

Carralyn Parkes is a labour councillor on Portland Town Council, currently serving as mayor.

"Our opposition has never been about asylum seekers," she says.

"These people will be treated with kindness, courtesy and respect and we will do everything in our power to make them feel welcome.

"It really isn't about being a Nimby (not in my back yard).

'Strange place'

"It's about the accommodation being offered which is wholly unsuitable for people with complex needs. It's barbarous and inhumane."

The town council has been clear in its opposition but also its powerlessness to resist.

Back on the garden wall, Mr Richards describes the leaflet posted through his letterbox a few weeks ago, reminding residents the Navy still occasionally uses the port as a back-up berth for nuclear submarines.

The sobering emergency plan informs everyone within a mile they will be handed iodine tablets if something goes wrong.

"Portland is a strange place," he concludes.

"A lot of weird things go on here."

He tells me he is "not a proper Portlander" because - even though he was born here - his parents were incomers or "kimberlin".

And now there are 500 more kimberlin - the as-yet unknown asylum seekers - who are voiceless and destined for the shelter of Portland's harbour with a storm raging around them.

Follow BBC South on Facebook, external, Twitter, external, or Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to south.newsonline@bbc.co.uk, external.

Related topics

- Published4 July 2023

- Published30 June 2023

- Published7 June 2023

- Published5 June 2023

- Published4 June 2023

- Published3 May 2023