Dancing the death drill: The sinking of the SS Mendi

- Published

In the pre-dawn darkness of a February morning in 1917, a ship carrying hundreds of black South African men was sunk in the English Channel. But this was no act of war. A Royal Mail cargo ship had ploughed full speed into the SS Mendi - and its captain inexplicably did nothing to help.

Who were these men and - 100 years later - has there been a lasting legacy from their deaths?

The vast majority of those who drowned or died from hypothermia were South Africans recruited to work as manual labourers on the Western Front.

Many had signed up hoping they would win more political freedoms if they demonstrated their willingness to help the British Empire's war effort.

More than 800 members of the South African Native Labour Corps were on board the Mendi at the time of the disaster

The Mendi had already completed a 34-day journey from Cape Town when it sailed past the Isle of Wight in foggy weather on 21 February.

At about 05:00 GMT, a Royal Mail packet-boat, the SS Darro, ploughed into the Mendi at full speed, smashing a 20ft (6m) hole on her starboard side. It ripped through to crowded holds where men were sleeping in tightly-packed tiers of bunks.

A total of 646 people died. Only 267 survived the sinking; 195 black men, two of the four white officers and 10 of the 17 white NCOs.

From the safety of the Darro, Captain Harry Stump stood by and watched - but for reasons that are still murky, did nothing to save the lives of the men.

Why didn't he help?

King George V inspected the South African Native Labour Corps at Abbeville on 10 July 1917

The SS Darro sustained only minor damage and there was plenty of room on board, according to the official investigation, external.

Survivors were instead picked up by the destroyer HMS Brisk and then other ships.

South African historian Professor Albert Grundlingh, said it was difficult to explain Cpt Stump's actions.

"It's shrouded in mystery," he said. "At a tribunal Cpt Stump said it was dark, and he couldn't see in the conditions. Maybe he was confused or lost his nerve.

"Was is because the men were black? There has certainly been speculation to that effect, but no firm conclusion. In South Africa, people believed that."

What was the South African Native Labour Corps?

The SANLC was formed in response to a British request for manual workers on the Western Front.

The men were to have become part of a huge multinational labour force.

Their role was to build the railways, trenches, camps and roads upon which the Allied war effort depended.

They were not allowed to bear arms, were kept segregated, and were not eligible for military honours.

Following the disaster, bodies continued to be washed up on both sides of the Channel for several weeks.

The news of the sinking reached South Africa two weeks after it happened. Prime Minister General Louis Botha rose in parliament to inform the nation, and the house unanimously carried a motion conveying "parliament's sadness". Botha praised the labour corps for "doing everything possible" in the war and for their "loyalty to the flag and the King".

This deference did not stretch to awarding medals to any of the black servicemen - living or dead - from the South African Native Labour Force. Such honours were reserved for white officers only.

The wreck of the SS Mendi has been designated an official military maritime grave

In the years that followed, the disaster was not made much of in South Africa.

Indeed, some African National Congress (ANC) leaders viewed war veterans as "sell-outs", according to Prof Grundlingh, and felt "embarrassed" about black military service.

Col Daisy Tshiloane, a former member of the ANC's military wing, said she had learned the story of the Mendi in "ANC camps".

Speaking as a South African deputy defence advisor in 2014, she said she found it "very hurtful" that "so many black African lives meant nothing".

The story was not included in school curriculums set by the country's white rulers but was passed on from generation to generation, says author Fred Khumalo.

"It's a huge gap in our history," says the writer of Dancing the Death Drill, a novel based on the sinking.

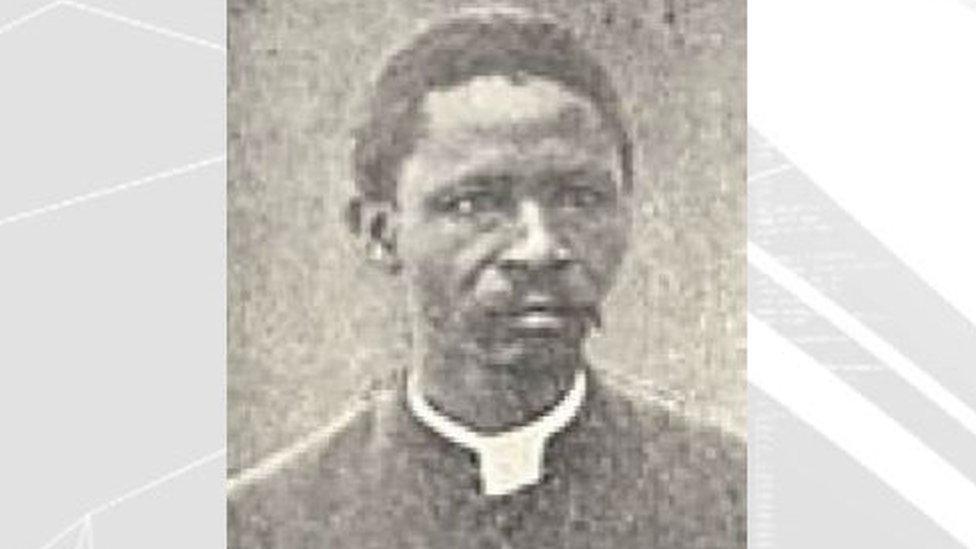

The book's title comes from an unconfirmed but persistent anecdote about Reverend Isaac Wauchope Dyobha, a pastor on the ship.

Reverend Isaac Dyobha reportedly told sailors, "You are going to die, but that is what you came to do".

He was a prominent member of a group of East Cape African intellectuals, who encouraged their compatriots to join the Labour Corps in the hope the show of loyalty would benefit black people politically.

The story goes that he told the doomed men:

"Be quiet and calm, my countrymen, for what is taking place now is exactly what you came to do.

"You are going to die, but that is what you came to do.

"Brothers, we are drilling the drill of death.

"I, a Xhosa, say you are all my brothers, Zulus, Swazis, Pondos, Basutos, we die like brothers.

"We are the sons of Africa.

"Raise your cries, brothers, for though they made us leave our weapons at our home, our voices are left with our bodies.

He then led them in a barefoot dance - the "death drill" - drumming their feet on the deck as the ship wallowed and sank.

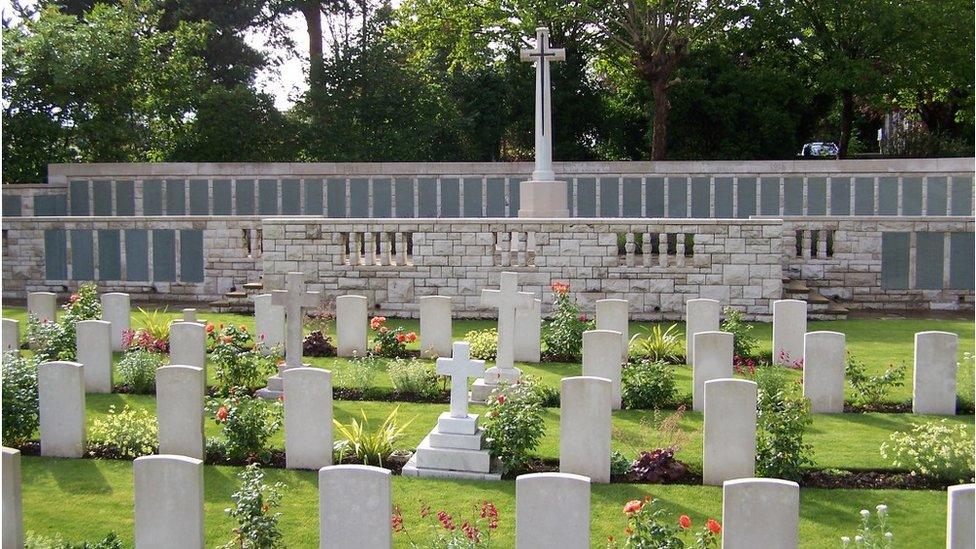

The Hollybrook memorial in Southampton lists the names of many of the Mendi victims

Historians have varyingly described the legend as "pure nationalist mythology based on African oral tradition" or containing a "solid core of truth".

Other stories of heroism include that of Joseph Tshite, a schoolmaster from near Pretoria, who encouraged those around him with hymns and prayers until he died. A white sergeant was supported by two black compatriots, who swam with him and found place for him on a raft.

A total of 646 men died in the tragedy - most of them members of the South African Native Labour Corps

The site of the wreck was discovered by an English diver in 1974 and an official memorial was erected by the South African government in 1986 at Delville Wood in France.

By then, South Africa's black majority had lived under decades of apartheid rule, the hopes that loyalty in WW1 would lead to greater political rights having been long dashed.

However, in post-apartheid South Africa, the story is now better known. A Mendi medal for bravery was established in 2003 and a modern South African navy ship bears its name.

A memorial for the SS Mendi in Simon's Town, South Africa

And the controversy over the actions - or lack of - by Cpt Stump rumbles on.

He was found entirely to blame for the sinking. An official report ruled he was going too fast and had not sounded a warning whistle in the fog.

According to Prof Grundlingh, the captain never explained why he did not help the stricken men on board the Mendi, nor express any regret or remorse.

Yet despite calls for him to be jailed, the only sanction he faced was to have his licence suspended for a year.

"He must have heard the cries proceeding from the water for hours [after the accident]," the report into the disaster said.

"There was nothing to have prevented him from sending boats on the then smooth water... had he done so, many more lives would have been saved.

"His inaction was inexcusable."