Kingston upon Hull: How a city created by a king sees the Coronation

- Published

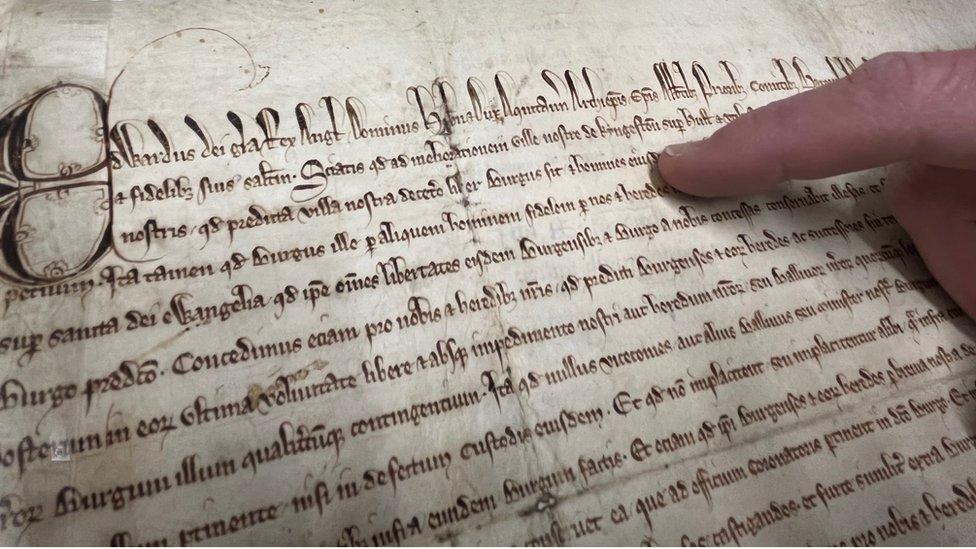

City archivist Martin Taylor examines Hull's royal charter of 1299

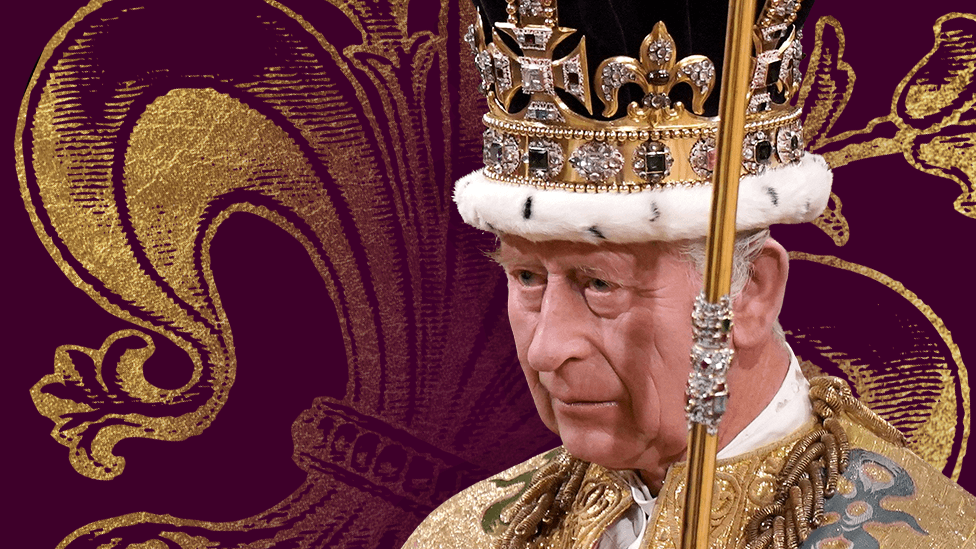

A city created by a king, which plotted against a second, is about to witness the coronation of a third.

BBC News' Kevin Shoesmith discovers the royal history behind Kingston upon Hull and finds out what people there have to say about the Coronation of King Charles III on Saturday.

It is considered the jewel in Hull's archive - the royal charter of 1299.

Or as city archivist Martin Taylor, the person charged with protecting the document, likes to call it: Hull's birth certificate.

Mr Taylor's finger hovers over the word Kingston.

"We were originally a strategic port called Wyke upon Hull," he tells me. "In 1293, it was bought by King Edward I who decided to rename it Kingston upon Hull."

Kingston upon Hull owes its name to Edward I who signed the city's royal charter in 1299

The document, etched onto parchment - treated animal skin - is occasionally put on public display, although its usual resting place is inside an unassuming, green cardboard box within Hull History Centre's inner sanctum.

The whirl of fans can be heard overhead; the climate is carefully controlled here, helping protect the 330,000 irreplaceable artefacts containing everything from poet Philip Larkin's letters to detailed wartime records.

Mr Taylor explains the granting of the charter afforded the citizens of Hull, as some later abbreviated it to, "certain privileges", including the right to hold a market and a fair.

However, for a city which owes its name to royalty its relations with monarchs have, to put it mildly, been strained.

In 1642, governor Sir John Hotham famously shut the gates to the city on King Charles I, who sought access to its arsenal.

It was an act of defiance said to have triggered the English Civil War.

Sam Millbank with Coronation bunting city centre promoters have been handing out

So, almost 400 years later, and given the history of this city, what do people here make of the forthcoming coronation of King Charles III?

"I couldn't care less," laughs Sam Millbank, a well-known figure on the Coyle & Sons greengrocer stall in King Edward Street.

From public gardens to playing fields and squares, Hull contains numerous nods to past monarchs.

Mr Millbank continues: "My wife is off down to London to take part in the celebrations. But I'm not going. It doesn't interest me."

He shows me a pack of bunting Hull BID, a group that promotes city centre businesses, has invited him to put up.

It remains in its polythene packaging - and is likely to remain so, he tells me while serving a customer.

Despite not being a fan of the royals, Mr Millbank tells me he respected the late Queen Elizabeth II.

"She was loyal," he says. "That's important for Hull. She stood by what she believed in."

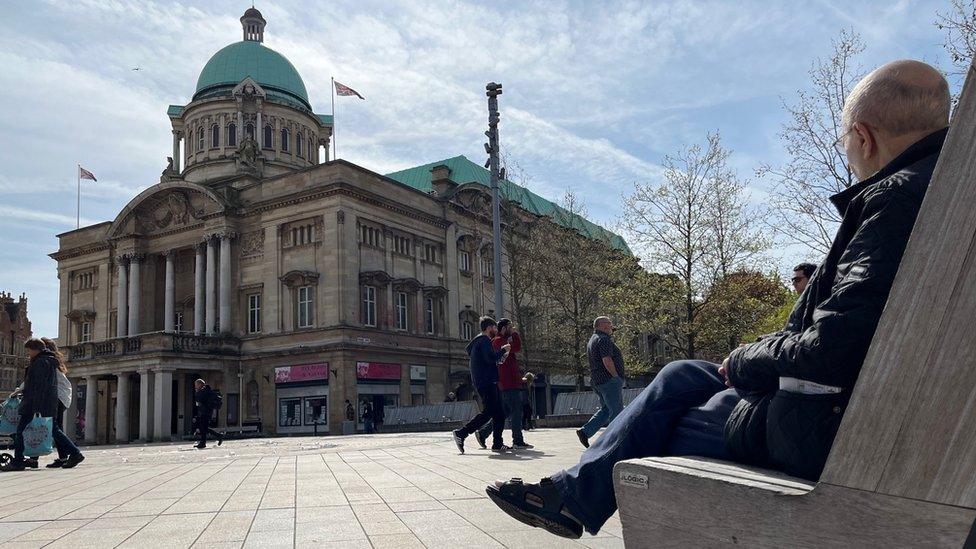

Union flags fly atop City Hall in Hull's Queen Victoria Square

In the shadow of Hull City Hall, I find retired accountant Dave McGarry sitting in the sunshine of Queen Victoria Square.

He seems unimpressed by the fanfare.

"The coronation is going to have no effect on me," says Mr McGarry. "I have no interest in it whatsoever."

In 1688, Ye Olde White Harte, then lodgings, was used to plot the seizure of Hull

I call into one of Hull's most historic pubs, Ye Olde White Harte, where in 1688 it is rumoured Capt Lionel Copley, then deputy governor, plotted to seize the city on behalf of William of Orange, later King William III.

Former Coldstream guardsman John Hope and his wife Jo are nursing drinks at the bar and are quick to extol the virtues of the Royal Family.

"The Queen wanted the crown to pass to Charles," says Mr Hope. "The Coronation is good for the country."

John and Jo Hope share their pro-monarchy views at Ye Olde Harte pub in Hull

Mrs Hope adds: "I camped out in London for the Queen's Jubilee and William and Kate's wedding. I like Charles. It would be nice if we saw him up here.

"He should visit places like Hull, given its history, more often."

I ask her why she is not there this time.

"I'm too old for that now," she says, chuckling.

Sitting at a table in front of a large fireplace are friends Dave Foot and Andy Ford who have conflicting views of the royals.

"I'm proud to be British," says Mr Ford. "I'm a royalist. Coronation day is something positive; something to look forward after all the news we've had about wars and Covid."

Mr Foot tells me: "I'm not a royalist. I think there is a divide in Hull. I do accept that the royals give us some culture.

"It keeps us away from the sad reality of capitalism."

Andy Ford, left, and Dave Foot talk monarchy at Ye Olde White Harte pub

Back among the cabinets containing Hull's written past, Mr Taylor opts not to pass comment on the latest monarch, explaining that is for the wider public, not him.

But he does offer a possible explanation as to why some here - even republicans - felt an affinity with the late Queen.

"She appealed to two strong Hull traits," says Mr Taylor. "Firstly, she really carried that World War Two vibe. She was involved in the war. She was in the services. Remember, this was a city that was bombed heavily in the war.

"Secondly, Hull recognises a matriarch when it sees one. Generations of strong Hull women raised families on their own while their husbands were away at sea. The famous Headscarf Revolutionaries - wives of fishermen who fought for improved safety on trawlers - are a case in point."

Follow BBC East Yorkshire and Lincolnshire on Facebook, external, Twitter, external, and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to yorkslincs.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published6 May 2023

- Published6 May 2023

- Published24 April 2023

- Published6 May 2023

- Published4 May 2023