The empty grave of Charles Dickens

- Published

Charles Dickens mentioned Rochester Cathedral in his first work, The Pickwick Papers, and in his last, unfinished, novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood

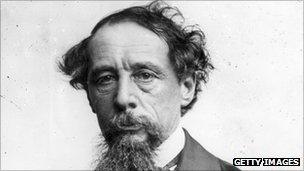

It reads like a plot from a Charles Dickens novel.

A Victorian gentleman's wishes are defied by an interfering and ambitious cleric, leaving a grave without a body in the hallowed Lady Chapel of Rochester Cathedral.

Yet this was the fate that befell Dickens himself, according to the acting Dean of Rochester Philip Hesketh.

The Victorian writer - whose fame had reached international proportions by the time he died of a stroke at his home in Higham in 1870 - had requested a simple funeral in the cemetery of the Kent cathedral, Mr Hesketh said.

But the cemetery was full and so the Dean and Chapter had a vault dug inside the building.

At the same time, the Dean of Westminster, Arthur Stanley, was searching for a famous writer to boost the standing of Westminster Abbey in British life, and Dickens was seen as the ideal candidate to be laid to rest in Poets' Corner.

'Should be here'

By the time the grave was ready to receive the body, Dickens's remains had been "whisked away", Mr Hesketh said.

It can be seen as a strange case of life mirroring Dickens's final artistic efforts - the author's last, unfinished work, The Mystery of Edwin Drood, centred on the suspense of the possibility of a corpse hidden in Rochester Cathedral.

The 200th anniversary of the birth of Dickens was on 7 February

Mr Hesketh said the turn of events on the novelist's death was recorded in the minutes of the cathedral, which the Victorian author knew and loved.

The acting dean said the "beautifully written" account showed the local feeling at the time, that the writer should have remained in Kent.

Dickens, who born in Portsmouth in 1812, spent some of his childhood in Chatham, and his last years at Gad's Hill in Higham.

As well as in The Mystery of Edwin Drood, Rochester Cathedral featured in his first work, The Pickwick Papers.

Dickens also knew the cathedral clergy - William Miles, the head verger at the time, is thought to have have inspired the character of Mr Tope in Drood.

Mr Hesketh said questions remained over the empty grave after Dickens's body was taken to London.

'Celebrity required'

"There was a lovely account in the Chapter records for 1870, dealing with the question of who is going to pay for having the vault dug.

"The Chapter is absolutely insistent that the expense should be theirs because of the high esteem that Dickens was held in - not only by the cathedral community but indeed the people of Rochester.

"It's just a beautiful record. It's beautifully written and I think there's an indication in those minutes when we read them that they still felt the more fitting place should have been here, and his body should have been laid to rest here."

Dickens expert Andrew Sanders said the Victorian author had become "an international superstar" by the time he died.

The emeritus professor at the University of Durham said for Dickens to have died with that level of fame was "an amazing feat".

Dickens ended up in the Abbey because in 1870, Dean Arthur Stanley had wanted a spectacular new burial for Poets' Corner, Prof Sanders said.

"There hadn't been a literary celebrity buried in Westminster Abbey since Dr Johnson at the end of the 18th Century."

He said the Romantic poets had either been too louche, like Byron, or too provincial, like Wordsworth, while the Bronte sisters were not seen as eminent enough, Thackeray had already gone to Kensal Green Cemetery, and Stanley had wanted a big name.

Charles Dickens lived at Gad's Hill Place in Higham, Kent, during the last years of his life

"Dickens was the most famous man of his time," Prof Sanders said.

"The problem was I don't really think Stanley liked Dickens's novels terribly. We've got it on record that he was rather indifferent to them.

"But he liked Dickens who he had met, he admired him, and he wanted the Abbey to be central to British life, and Dickens was the first coup."

Prof Sanders added: "The writer had wanted his reputation to be based on what he had written.

"I think it still is, essentially.

"Dickens is alive to us because of what he wrote. What we then do with it is another matter. We make films. We make television. We do what we want.

"But essentially it's his written word. That was his monument."

- Published1 February 2012

- Published16 January 2012

- Published10 January 2012

- Published15 December 2011

- Published11 November 2010