From England to Australia: Life for a real Ten Pound Pom

- Published

Ten Pound Poms has been shown in both the UK and Australia

"It was huge...and red....and desolate. And I just thought, oh my goodness, where have we come to?"

Glynis Rosser had just turned eight when she and her family arrived in Australia after registering on the 'ten pound Poms' scheme - the focus of the BBC's current big-budget drama.

About 4m viewers in the UK, external have tuned in to the series, which has also been screened in Australia.

The six-parter, whose finale is due to air on BBC One this Sunday, has sparked interest in a little-known part of modern history - when Brits left post-war austerity in search of sunshine and opportunities down under.

For some, the dream turned into a nightmare when they were housed in former war camps and faced hostility from some locals.

However, for others, it led to prospects that were unavailable back home.

Dr Jim Hammerton, who interviewed several British emigrants for his book Ten Pound Poms: Australia's Invisible Migrants, says: "To get on a boat for six weeks and go to an unknown continent was a huge thing. It could be devastating, and it could be wonderful."

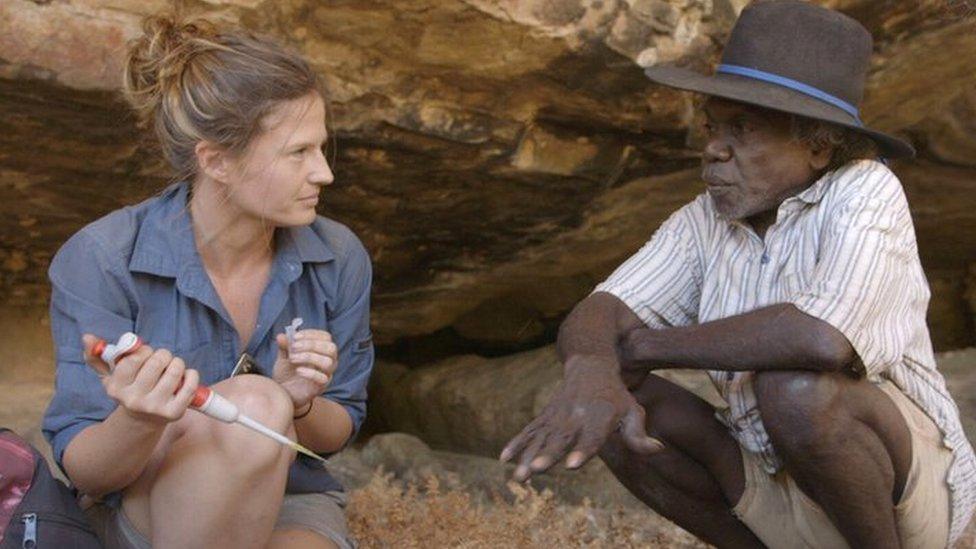

Glynis Rosser (right) and her mum getting their vaccinations before travelling to Australia in 1967

Ms Rosser says her parents' main motivation was to "give my sister and me easy access to opportunities".

She describes her Kent-born mother, and her father, from Newport - who both left school at 14 - as being "bright" but lacking prospects for a better life at home.

Her father took jobs from shovelling coal to driving a taxi, while her mother worked in a sweet shop.

It was during her father's time in the Merchant Navy that he saw the openings available for migrants from the UK, which led to the family enrolling on the so-called 'ten pound Pom' scheme.

Officially known as the Assisted Passage Migration Scheme, the cut-price offer to move to the other side of the world - for about £315 in today's money - was advertised with better job prospects and a sunnier future for any children.

Ms Rosser remembers the dry heat being a "challenge" after their arrival in 1967, particularly at a time when air conditioning wasn't readily accessible.

Their initial accommodation was similar to the wartime huts depicted in the drama, and they met a family there who hadn't moved for two years.

"My dad was so appalled by the conditions," Ms Rosser said.

"He was very enterprising and went out the next day, got a newspaper and found a job as a photographer."

The family only stayed for two nights in the basic camp conditions before they moved into a two-bedroom flat furnished with a bed and fridge.

Ms Rosser's father took this photo of their initial accommodation in Australia

It wasn't the first time that Brits were encouraged to move to Australia.

Since the 1830s, external - following the British colonisation of Australia - people from the British Isles had been paid or subsidised to migrate in order to boost the economic prospects of both countries.

"The larger picture was that, after World War Two in Australia, there was a very small population of about 10 million people," Dr Hammerton says.

The government feared being "swamped by Asia, particularly by China", he says, and so launched migration programmes to increase the population.

He adds that there was a "pro-British sentiment built in", particularly amid the backdrop of the White Australia policy, external that had formalised the restriction of non-white immigration since 1901, while enabling Brits to relocate.

"Britain was in a series of post-war shortages, so it was seen as logical to transfer what was seen at the time as excess population," Dr Hammerton says.

The ten pound Pom scheme targeted families and single women because of Australia's demand for labour and a bigger population, with the skilled working classes mainly taking up the offer.

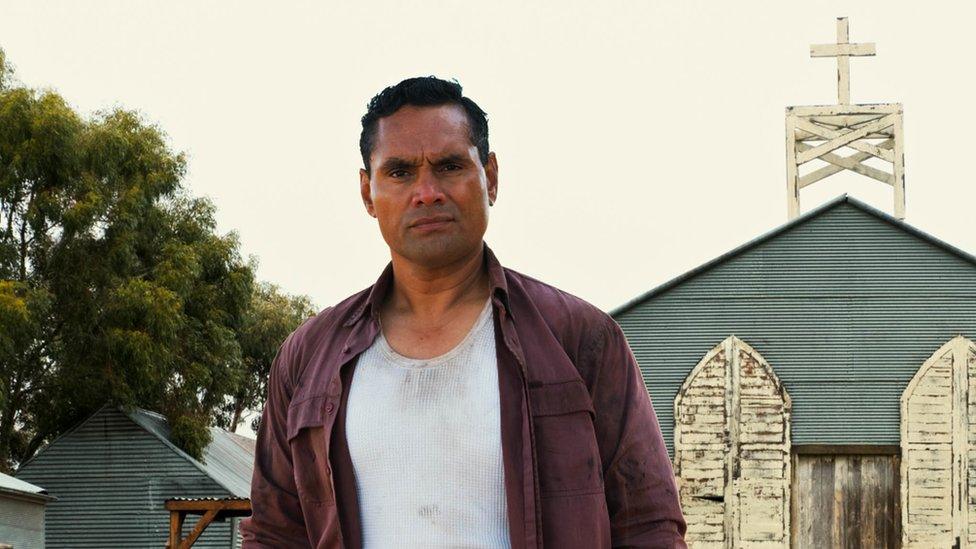

Actor Rob Collins says the drama also highlights the experience of Indigneous communities in a world "set against them"

While the cost increased some decades later, more than a million Brits, external emigrated between 1947 and 1981, most of them as part of the assisted passage scheme.

Ms Rosser recalls that "some of the promotional material was a bit misleading", adding that those who "put their back into it" eventually did manage to build a new life.

"The Australian culture wasn't hard to adjust to - it was different - but a hot Christmas did feel so alien," she said.

She says there was hostility "to a certain extent" from some locals, adding: "I was teased at school because I was pale and I never got tanned - I only used to burn - and because of my English accent.

"This is a country full of migrants, so that whole thing passes after a while."

Widespread migration also meant "a common theme was missing your family", she says.

The homesickness led to a quarter of British migrants returning to the UK.

Dr Hammerton said there were "complex reasons" for the returnees.

"Some never adjusted, they didn't like the climate, the people, the work that was available and they missed things about Britain," he said.

"Most migrants will have complaints about their new home because everything's strange. The British were no exception, but most Australians didn't really like that."

Hence the term "whingeing Pom" was coined, he wryly adds.

Glynis Rosser with her daughter Susanne on a trip to New Zealand

But at least a third of the British returnees moved back to Australia, leading to the phenomenon of 'Boomerang Poms'.

As one of them, Ms Rosser remembers feeling "out of place" after she returned to Chatham after spending her formative years away, to the extent she now had an Australian accent.

She felt like she had "come back home" when they relocated a few years later to Sydney.

The Ten Pound Poms drama, featuring Michelle Keegan and Warren Brown, shows Brits facing challenges while adjusting abroad and being accommodated in difficult conditions.

After watching the first episodes, Dr Hammerton points out that, unlike in the series, most of the huts were based in cities and suburbs to increase employment, and it was rare to be in the outback.

Prejudices about class and regional differences also existed within the migrant community, so the drama seems "a bit unrealistic in showing British migrant workers getting friendly with the Aboriginal characters, but some were", he adds.

"There are a few rags-to-riches stories but the vast majority did well in their chosen occupation and they managed to get their big dream, which was to get their own house."

Speaking from Adelaide, where she is now a manager providing elderly care, Ms Rosser says: "I really feel grateful for the opportunities. I had a free education to a very high level.

"I've heard stories of some feeling ripped off [by the migration schemes] but I fail to understand that perception.

"Like anywhere, you have to work for what you want and if you had the opportunity, it could work out as it did for so many of us."

Australia and migration

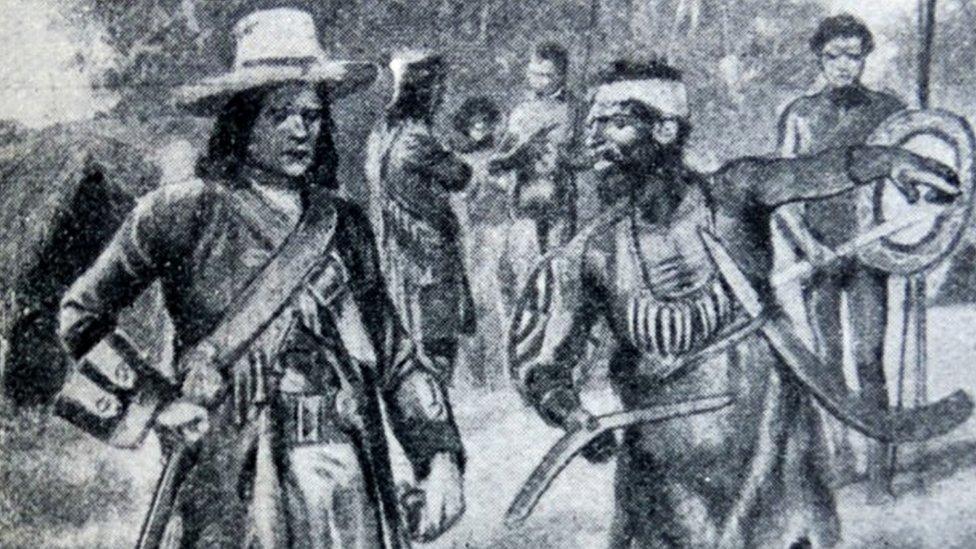

An 18th Century image shows William Dampier (left), who was the first Englishman to chart part of the Australian coastline in the late 1600s

The country's first inhabitants - the Aboriginal people - are believed to have migrated from Asia many thousands of years before the establishment of a British colony, external in 1788

It was called various names by the Indigenous population before Australia, external - derived from the Latin word for southern - was officially used from the early 1800s

Merchants and explorers from Asia and Europe visited the continent long before Captain James Cook claimed possession of the east coast for the British Crown in 1770

Britain transported convicts to Australia from the 1780s following pressure on its prison system, but some historians, external believe they also used it as a base for power in the wider region

Non-white immigration was limited, external between 1901 and 1958 to help keep the land "British", while other parts of the White Australia policy continued into the 1970s

Aboriginal people, who experienced dehumanising treatment including the forced removal of children from their families, external and land confiscation, now make up about 3% of Australia's population

Related topics

- Published25 January 2023

- Published23 September 2022

- Published29 August 2018

- Published20 May 2016

- Published20 July 2017