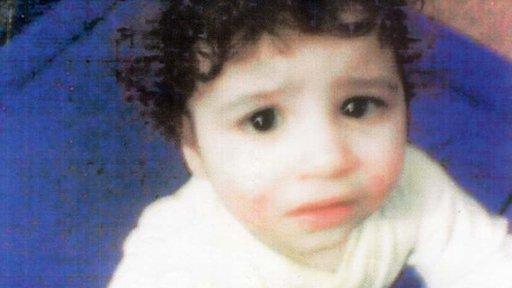

Hamzah Khan: How could boy starve to death?

- Published

Amanda Hutton denied Hamzah's manslaughter but admitted the neglect of her other young children

Hamzah Khan starved at the hands of his mother after a short life filled with violence and neglect.

Domestic violence within his home and a lack of medical care and proper diet should have caused alarm among authorities who dealt with his family, neighbours and a children's charity have said.

The four-year-old boy, described by neighbours as "pale and weak" looking, was wearing baby clothes at the time of his death and was suffering osteoporosis as a result of a "grossly inadequate" diet.

His mother Amanda Hutton hid his death from family, friends and the authorities and it was nearly two years before his mummified body was found in his cot, clutching his favourite soft toy.

Throughout Hamzah's life, Hutton had tried to avoid health professionals having any access to him. She refused entry to health visitors who called at the home, Hamzah was never given any immunisations and never saw a GP.

Hamzah's father Aftab Khan was said in court to have been violent towards Amanda Hutton

Until a year before his death there was also domestic violence in Hamzah's home.

Hutton started seeing Aftab Khan when she was a teenager, and told her trial that he was violent towards her throughout their relationship.

She reported him to police several times, before leaving him in 2008, and officers occasionally visited the family home.

Hamzah should have started primary school in September 2010 - a year before his body was found - but Hutton answered questions about his absence by claiming he was in Portsmouth with an uncle.

One woman who lived two doors away, who has asked to be called Mrs Khan, said: "In this day and age it's really hard to understand how someone can starve to death, especially in England.

"I know what she's done is wrong but the schools, the council, everyone should have picked up on that, that child should have been in school.

"Neighbours on the street have contacted social services, what happened to those concerns, what happened to those calls, did they just fly through the net? Something has gone wrong somewhere."

Bradford's social services department has so far refused to comment on their involvement with the family.

'Right to privacy'

David Tucker, the NSPCC's associate head of policy, said: "We're very concerned at the way he seemed to be able to drop off the radar, that services didn't seem to be able to check up on him, that the community seemed to be taken in by the story that the mother said and also that the family seemed to be unable to check effectively on his welfare either.

"There were instances of domestic violence, we don't know how severe those were and we don't really know at this stage what action was taken to follow those up.

"We really need to understand why it is that people continue to miss the signs that neglect is getting more serious and affecting a child in such a way as with this case for poor Hamzah, he ends up dying of starvation."

While the majority of parents do take their children to a GP, arrange for them to have immunisations and regularly see a health visitor, there is no legal requirement to do so.

Dr Bernard Gallagher, a reader in social work and applied social studies at the University of Huddersfield, said families did have a right to make their own decisions about their children's care.

He said: "We have to remember that while you want ideally for a child and his or her parents to be in contact with agencies such as health visitors, families have a right to privacy as well.

"Short of having CCTV cameras in people's houses we are not going to know what's going on with children all the time and neither should we know what's going on with children all the time."

Dr Gallagher said a serious case review of the involvement of agencies with the family would determine whether any mistakes had been made.

He said: "My initial impression is that maybe nothing in particular has gone wrong.

"Clearly some agencies were involved such as the police because there were reports of domestic violence but I can't imagine that any agency had any indication of anything serious going on to the children in the family because if they had done then they would have reacted."

West Yorkshire Police said its officers did carry out welfare checks on the children, including Hamzah, while investigating reports of domestic violence.

Det Supt Lisa Griffin, the officer in charge of the investigation into Hamzah's death, said the last police visit to the house was made in April 2009, eight months before Hamzah's death.

'Significant deterioration'

"We made a welfare check of the home address, the condition of the house was checked and the children were all presented to the police officer who attended and they all seemed to be fit and well," she said.

"That said police officers are not health professionals, they make an assessment based on their own personal judgement."

The detective said conditions in the home when Hamzah's body was found were "appalling" and she said there had clearly been a "significant deterioration" in Hutton's ability to care for her children after that April visit.

Hutton has been convicted of the manslaughter of Hamzah by gross negligence. She admitted preventing the burial of his body and the neglect of her five other young children.

Det Supt Griffin said the force would take note of any findings from the serious case review but ultimately Hutton was responsible for her son's death.

"It was her responsibility and hers alone to ensure that all their basic needs were met and that they lived a happy and fulfilled life and clearly she failed in that.

"As a mother myself I found that appalling, that she should have allowed this set of circumstance to play out as it did and that poor child to suffer in the way that he did."

- Published3 October 2013

- Published3 October 2013

- Published25 September 2013

- Published24 September 2013

- Published20 September 2013

- Published19 September 2013

- Published18 September 2013