Settle-Carlisle line thriving 30 years on after closure threat

- Published

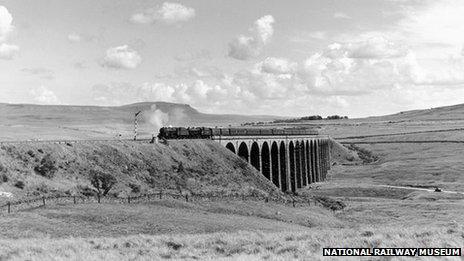

The dramatic Ribblehead viaduct is one of 20 such structures built by Victorian engineers along the Settle-Carlisle line

It was exactly 30 years ago that British Rail first announced plans to close the famous Settle to Carlisle railway, one of the last great main lines of the Victorian era.

But campaigners fought hard to save it and now it is a thriving route, clocking up 1.2 million journeys a year.

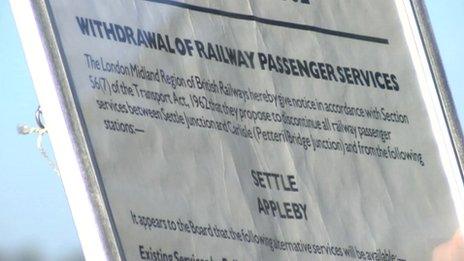

Rumours about British Rail's secret plan to shut the Settle-Carlisle line had been circulating for years. Then in December 1983 there it was in cold, hard print. Official closure notices displayed at stations on the line informing passengers that from May 1984 trains would be withdrawn.

Seventy-two miles of what was one of the last great Victorian infrastructure projects faced the imminent prospect of being wiped off Britain's railway map. The track would be lifted, stations boarded up and viaducts and tunnels left to decay.

In the 1960s about 5,000 miles of railway line had met a similar fate following the publication of the now-infamous Beeching Report. Protesters had tried to prevent the axe falling on routes across the country, but with little success.

For five-and-a-half years it seemed the Settle-Carlisle line was heading in the same direction; the line would become no more than another lost link through spectacular scenery.

The closure notices which appeared in December 1983 had to be withdrawn because of a legal error

But fortune smiled on the Settle-Carlisle, because that blunt and drily-worded closure poster contained a legal error meaning the posters had to be taken down, reprinted and reissued.

That delay gave the newly-formed Friends of the Settle-Carlisle Line vital time to get organised and encourage objectors to write letters.

John Moorhouse, who was the chairman of the North West Transport Users Consultative Committee, played a key role in fighting the closure and says the unexpected level of opposition to the plan gave some hope.

"You had to be optimistic, the objections kept mounting up and I think that closure notice being reissued was a big help in the campaign to keep the line open," he said.

"Also shutting the line was opposed by the local authorities, they came together and made a very good case to keep it open."

All the extra publicity that the Settle-Carlisle was receiving meant that passenger numbers started to rise.

Visitors to the Yorkshire Dales and Cumbria's Eden Valley started leaving their cars at home and catching the train instead, believing it might be the last chance they would get to travel over Ribblehead Viaduct or through England's highest mainline station at Dent.

That rise in passenger numbers meant British Rail had to increase the number of services it operated over the route and, for the first time since the 1960s, the spiral of decline had been halted.

However, British Rail had other reasons for advocating closure and the dilapidated state of the viaduct at Ribblehead was one. Built in 1870 the 100ft (30m) high structure was in desperate need of repair.

Official estimates put the price at £7m, but the campaigners found engineers who could prove that the work could be carried out at a fraction of the cost.

The arguments against closure were diminishing, but the railway was still sucking up public money and it was presumed the pro-road Conservative government would eventually give closure the green flag.

The final decision would rest with the then Minister of State for Transport and Thatcher loyalist Michael Portillo.

'Closing down sale'

Almost without warning in May 1989, Portillo told British Rail he was refusing permission to close the railway. Looking back he has admitted it was a difficult decision.

"There was awkwardness because Conservatives want to do two things, they want public services to run efficiently, so we wanted to reduce public subsidy to the railway line, but we also had a respect for the national heritage and we knew it was a very remarkable and historic line," he said.

"Fortunately we managed to bring the two things together, because the economic case for closure was very much weakened when vast numbers of people began to travel on the line.

"There was a sort of closing down sale and also some very clever engineers discovered they could do the job of restoring the Victorian structures much more cheaply than we thought."

The Settle-Carlisle line had been thrown a lifeline by a sympathetic minister, who had more than a passing interest in the history of Britain's railways.

Since 1989 the line has boomed. Last year there were 1.2 million passenger journeys compared with just 90,000 in the dark days of 1983.

The Waverley Express crosses the Ribblehead Viaduct circa 1958 with the slopes of Pen-y-Ghent visible in the background

The railway also carries timber from a line-side forest and provides a route for heavily-loaded coal trains that make their way from Scotland to Yorkshire's power stations.

Mr Moorhouse makes the point that if British Rail had got their way some of that traffic would instead be crawling along roads in the Yorkshire Dales.

With privatisation British Rail disappeared in the 1990s and the increasingly popular passenger trains are now operated by Northern Rail, which regards the route as a jewel in its crown.

Drew Haley, who helps co-ordinate the promotion of the line for the company, says he is glad the closure poster was published 30 years ago.

"The closure notice was the best thing that could happen to this railway, because what doesn't kill you actually makes you stronger and now the stations look fantastic, there's a lot more trains and there's hundreds of thousands of extra people using this line every year, from all over the world," he said.

So what does the future hold? Those campaigners who realised the line was an asset back in 1983 are now calling for a direct service into Manchester to create even more journey opportunities and after 30 years campaigning to save the line the chairman of the Friends of the Settle Carlisle Line Mark Rand has said he can finally say the line is secure.

He said: "I think the likelihood of us seeing in the future a notice of closure for this railway line is hugely, hugely unlikely. This line is here to stay now."

Few would have believed that in December 1983.

- Published7 June 2013

- Published25 March 2013