Huddersfield grooming: How the West Yorkshire gang operated

- Published

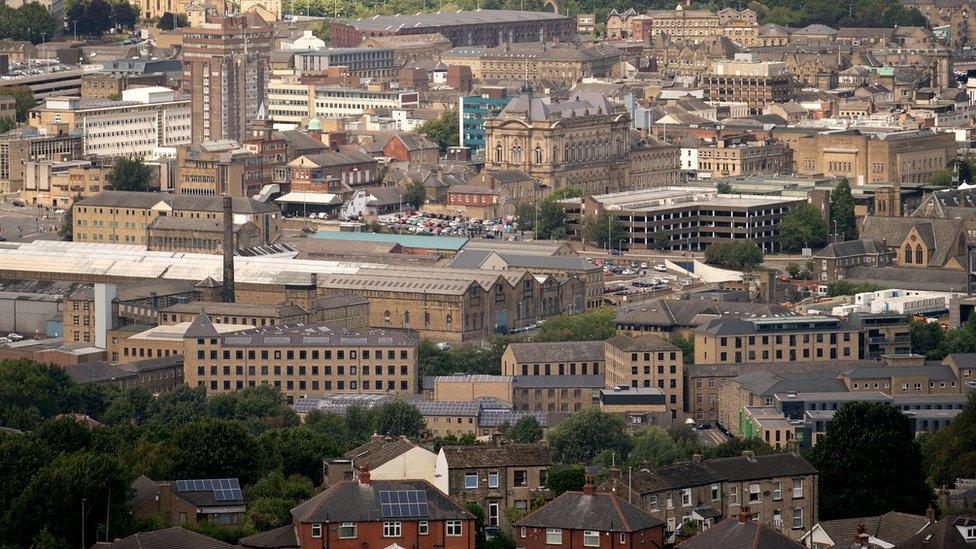

The abuse took place in and around Huddersfield between 2004 and 2011

A gang of men who abused vulnerable teenage girls in Huddersfield has been given lengthy jail sentences. How did these sex offenders from West Yorkshire, who were convicted of more than 120 offences against 15 girls, operate?

How did the abusers control their victims?

The men, who are all British Asians mainly of Pakistani heritage, groomed girls by making them feel special, then plying them with alcohol, cannabis and other drugs.

They then used violence and threats to control them, on one occasion threatening to bomb a girl's family home.

The victims were often taken to parties where they were given drink and drugs and forced to have sex with men who were sometimes decades older than them.

On other occasions they were sexually assaulted in car parks, above takeaways, at snooker clubs and in parks around West Yorkshire.

Some were raped and abused as part of "truth or dare games" while others were abandoned on the moors late at night if they refused to do what they were told.

One girl was raped by the gang's leader as punishment for "showing him up" after she refused to perform a sex act on another man in the back of a car.

The same girl was also forced to have an abortion and told the court she had no idea whose baby it was.

Another girl was abducted from the children's home she was staying in and taken and abused on the moors when she was just 12.

Who were the men?

The men, all from Yorkshire, went by nicknames including "Dracula", "Bully", "Beastie" and "Nurse"

A large amount of the grooming and abuse was carried out by the gang's ringleader Amere Singh Dhaliwal, a Sikh man who was known by the nickname Pretos.

The now-married father-of-two was convicted of attacks on 11 of the 15 girls.

His treatment of his victims was described by Judge Marson as "inhuman".

The other men - aged between 27 and 54 - were equally described as "predatory and perverted".

In total 20 men, from Huddersfield, Sheffield, Bradford and Dewsbury, have been convicted and sentenced for their part in the abuse.

The court heard many other perpetrators have not been identified and girls spoke of being abused by men they heard being called "Mangos" - a term used for men from Pakistan who did not really speak English.

Prosecutor Richard Wright QC told the court: "These men cared only for themselves and viewed these girls as objects to be used an abused at will.

"These men did not only control the girls by grooming them, they were also quite capable of employing threats of violence if the need arose, on occasion using violence and threats to control them and force them into sexual activity against their will."

Who did the gang target?

In total 15 girls aged between 11 and 17 fell victim to the gang.

Many of them were socially isolated and as such became "easy targets for abuse", the court heard.

Among the victims were girls with mild learning disabilities, girls who were bullied at school; one girl's mother was completely unable to look after her because of her own drink and drug problems.

As a result they often craved the attention they were given, leaving them unable to see what was being done to them until it was too late.

The court heard some of the victims felt they were in genuine relationships, such was the extent to which they had been groomed.

How did the victims remain in the gang's grip?

Over the course of the three trials jurors listened as the gang's victims recounted how they had been groomed and exploited over many years, unable to escape.

"I suppose when you're young and you get bullied at school you do sort of like the attention, and things getting bought for you and stuff, but then once you were in with them you couldn't get out of it," one girl said.

"They got your trust and then stuff would start happening to you. I was constantly getting raped and beaten up."

Another, when asked why she kept going back to the men said: "They just threatened me - 'I'm coming to pick you up now and if you don't come, I'm coming to get your mum'."

Such was the men's hold over the girls one woman said her daughter cracked her head jumping from a first floor balcony at their home in order to get out.

The girl later told police: "Every time I went out something bad happened. I risked my life every time. I was a mess."

One victim, who only escaped her abusers when her family was forced to move out of the area following a house fire, said: "It was the best thing I ever did, and that's bad saying that burning your house down is the best thing you ever did."

Speaking to detectives many years later one girl said: "I always bugged myself - 'why did I go back?' - and I still cannot answer that question.

"For years and years I blamed myself that it was my fault I went back, [but] they're quite manipulative and when you're in that situation you're so pressured, you feel so stupid and dirty and horrible."

When did the abuse come to light?

Nazir Afzal, the prosecutor in the Rochdale grooming gang in 2012, tells Radio 4's PM programme that the fear of being called racist should not be used as an excuse for not investigating these men

Victims and their families say they repeatedly told police and the authorities what was happening at the time but that it had fallen on deaf ears. One woman said she had even written to the Prime Minister.

One girl said when she tried to tell two officers who took her to hospital after she was assaulted by one of her abusers they told her "you must have wanted it".

The first allegations to be taken seriously surfaced in 2011 when a victim wrote a letter to a judge outlining the abuse she had suffered, but she did not make a formal complaint.

It was not until 2013 that another victim came forward to police to make formal allegations against two gang members, Nasarat Hussain and Irfan Ahmed.

Over the following three years dozens of girls and men were interviewed.

Then in March 2017 a total of 29 people were initially charged as part of what became known as Operation Tendersea.

Why have these trials not been reported on before?

Details of the convictions and lengthy jail sentences imposed can only now be reported as a blanket ban on coverage put in place in November 2017 was lifted following an application by the media.

The press restrictions were put in place under the 1981 Contempt of Court Act, which allows a judge to stop reporting of a case to avoid prejudice and protect the integrity of the hearing or any future hearings.

That ban on coverage, however, has attracted criticism from certain groups, including those with links to the far-right.

In May, the former leader of the English Defence League Tommy Robinson was jailed for 13 months after he admitted a charge of contempt for filming outside Leeds Crown Court during the second of three trials.

The footage, lasting about an hour-and-a-half, of Robinson discussing the trial was watched 250,000 times within hours of being posted as a Facebook Live.

On appeal, however, Robinson's conviction was quashed because of a number of procedural errors, though he faces a fresh hearing in relation to the alleged breach later this year.

- Published19 October 2018

- Published19 October 2018

- Published19 October 2018