'Great Escape' anniversary: The last man in the tunnel queue

- Published

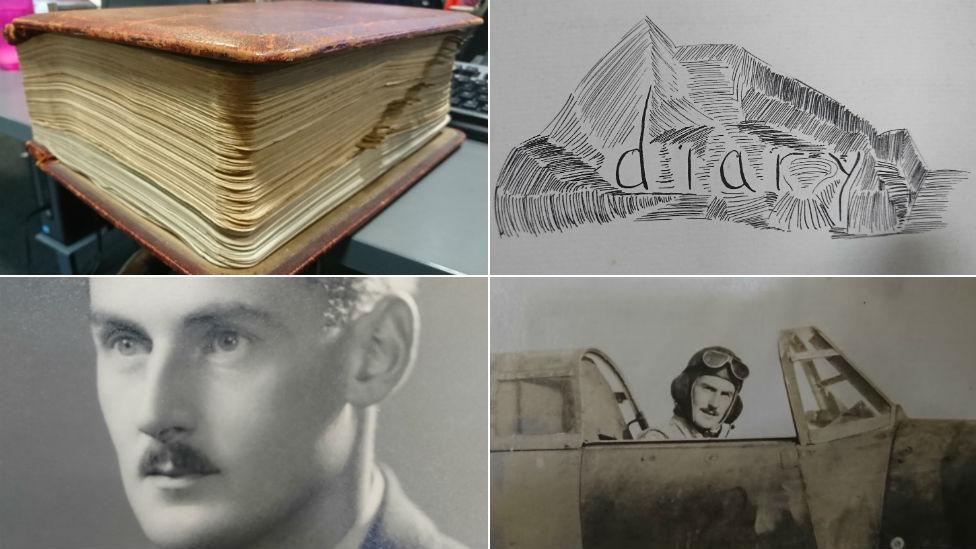

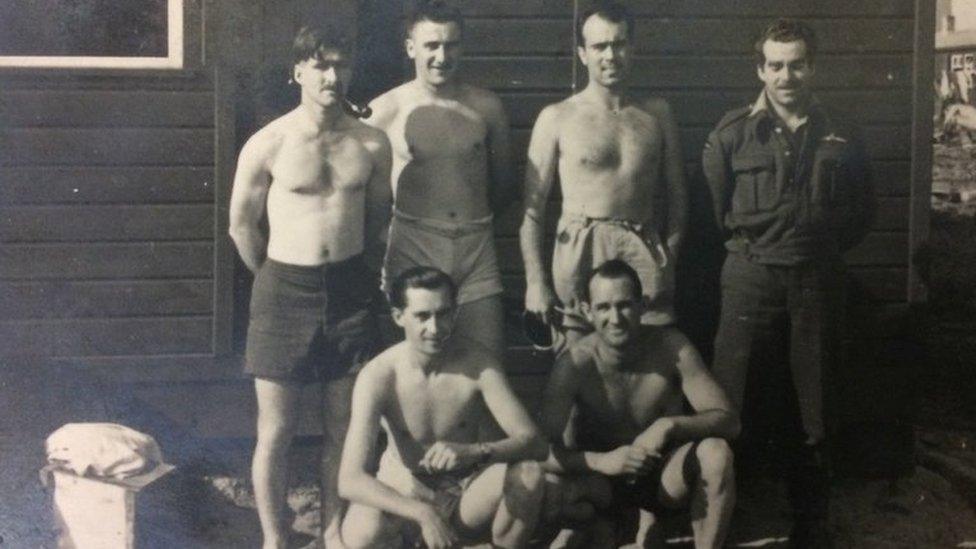

Marcel Zillessen was shot down while flying a Hurricane in north Africa and taken prisoner in 1943

The diary of a World War Two prisoner who inspired one of the characters in The Great Escape film has been shared for the first time to mark the 75th anniversary of the breakout.

Marcel Zillessen was last in the queue of 200 men waiting to crawl through a tunnel at Stalag Luft III, but the alarm was raised before his turn came.

His diary describes how he later escaped the deadly Long March in 1945 by fleeing into a forest and hiding.

He died in 1999 aged 81.

Born in 1917 to a German father and Irish mother, Flying Officer Zillessen spent his early life in Bradford, West Yorkshire, working in the family textile business until the war broke out.

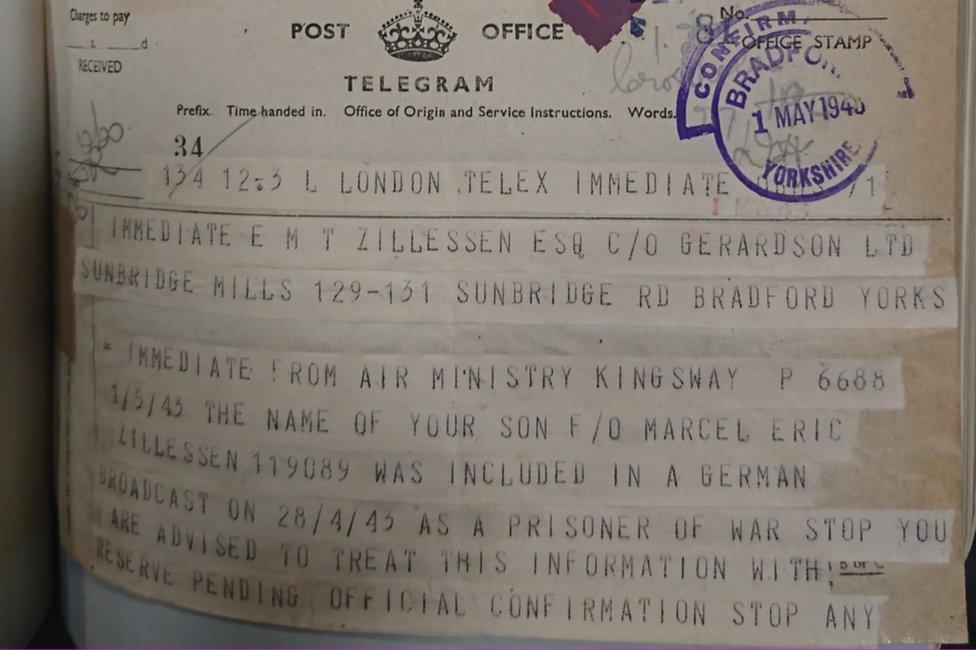

Marcel Zillessen's family was sent a telegram warning it was likely their son had been captured as a prisoner of war

Shot down while flying a Hurricane in north Africa in 1943, he was taken to the Luftwaffe-run prisoner of war camp holding Allied air force personnel, 100 miles south east of Berlin.

On life inside the wire fences, Flying Officer Zillessen wrote: "We are a community, are individually beneficial in some way or another and we cope.

"Tolerance and generosity abound but are somehow not quite real."

Flying Officer Zillessen's wartime diaries were shared with the BBC by his son Tim

Fluent in German having been to university in Berlin, he translated the works of German poets to pass the time.

Flying Officer Zillessen's language skills made him unique among the thousands of men held at Stalag Luft III, and he was pounced upon within weeks of arriving to help prepare the escape plot.

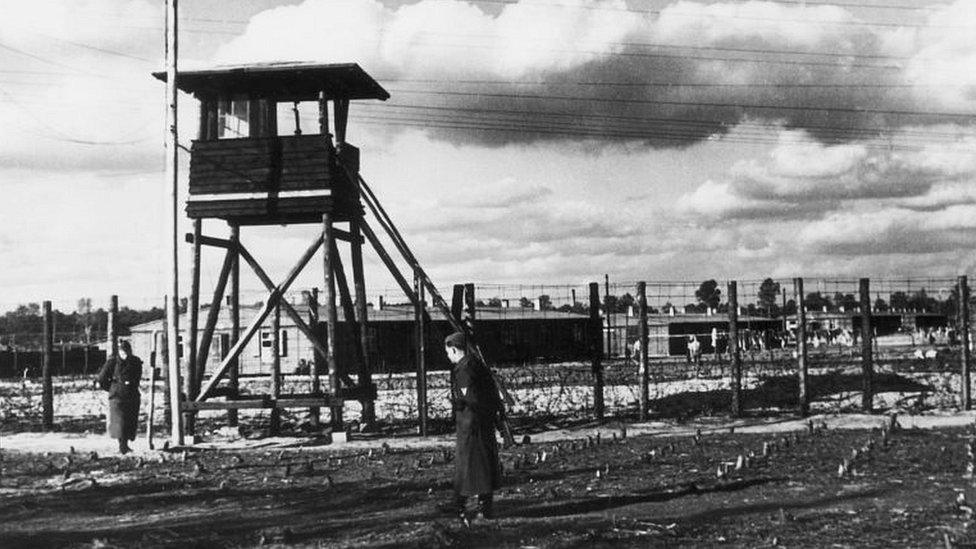

Stalag Luft III was run by the Luftwaffe until its liberation on 29 April 1945

In a 1979 newspaper interview with his son, journalist Tim Zillessen, Flying Officer Zillessen said: "One day, a member of the escape organisation walked me round the circuit of the camp and told me my talents were just suitable for a particular job they needed doing - that was the anti-ferret".

Tim Zillessen travelled to the site of Stalag Luft III to see where his father Marcel was held

The "ferret" was a guard who went around the camp sticking poles in the sandy ground to try to locate escape tunnels.

The Great Escape

Stalag Luft III opened in spring 1942, and held air forces personnel only

At its height it held 10,000 prisoners of war, covered 59 acres and had five miles (8km) of perimeter fencing

Some 600 prisoners helped dig three tunnels, which were referred to as Tom, Dick and Harry

The "Great Escape" happened on the night of 24 to 25 March, 1944

Seventy-six men attempted a getaway through tunnel Harry, which was 102m (336ft) long and 8.5m deep

Seventy-three of them were recaptured by the Germans within three days. Fifty were executed on Hitler's orders

The camp was liberated by Soviet forces in January 1945

Flying Officer Zillessen built up such a rapport with the guard he was able to gain valuable items such as paper, pens and ink to help forge travel documents for escapees.

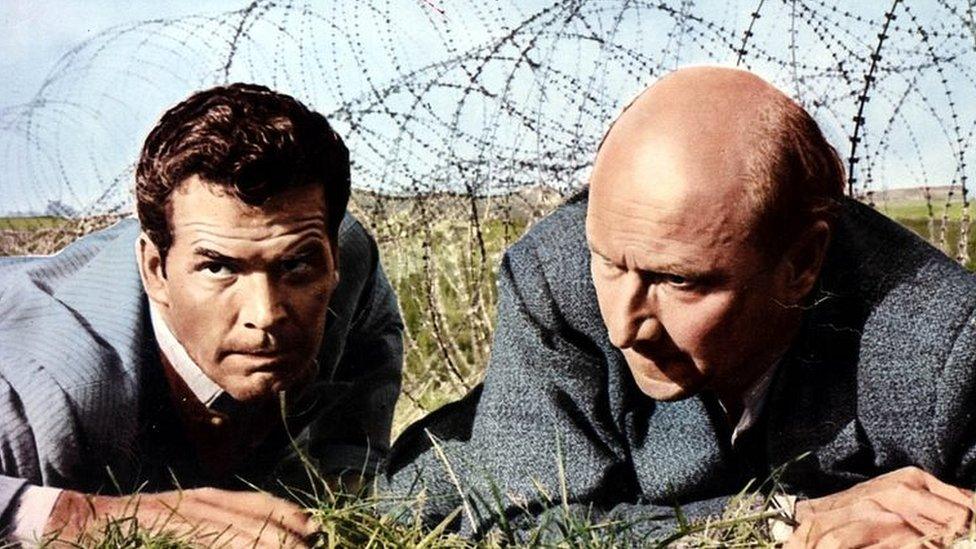

It is believed James Garner's 'Scrounger' from the 1963 classic film was based on Mr Zillessen, although he argued it was a "composite" of several men to avoid having too many characters.

"It took two or three months to get [the German guard] completely tamed, but in a film all that work has to be shown in two or three minutes," Flying Officer Zillessen said in 1979.

It is widely considered that Marcel Zillessen inspired James Garner's "the scrounger" character (left) in the 1963 classic film The Great Escape

Despite having a key role in the preparations for the escape, Flying Officer Zillessen was at the back of the line to go through the 'Harry' tunnel and fled back to his hut when the plot was foiled.

Mr Zillessen, from Malham, North Yorkshire, said: "My father was the last to go because everybody knew that with his skills and languages, once he got out he would have been a free man.

"The upside of [being last] is that he didn't get out, so he wasn't one of the 50 that were shot."

He remained in the camp until the war was nearing its end, when thousands of PoWs were forced to march in winter from the camp in Sagan - now Zagan in Poland - to Spremberg in eastern Germany.

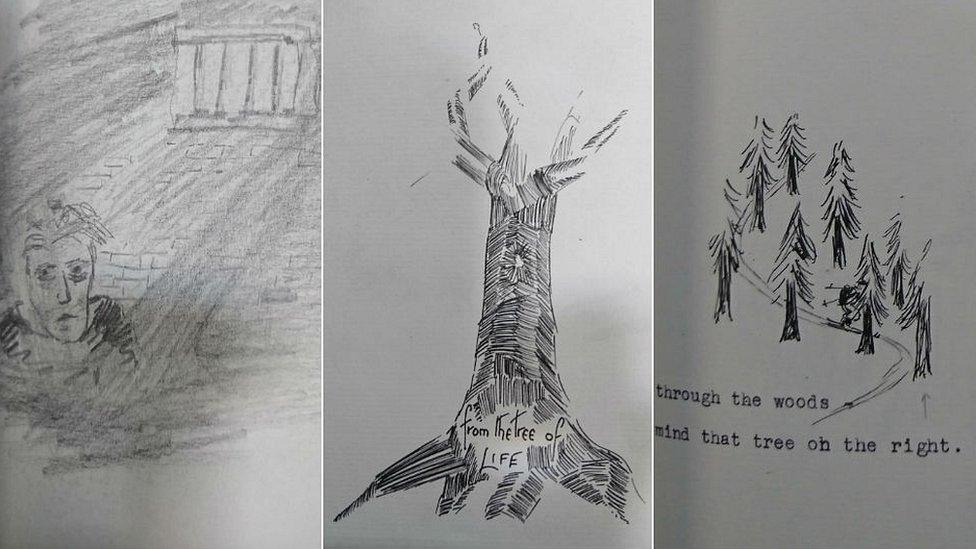

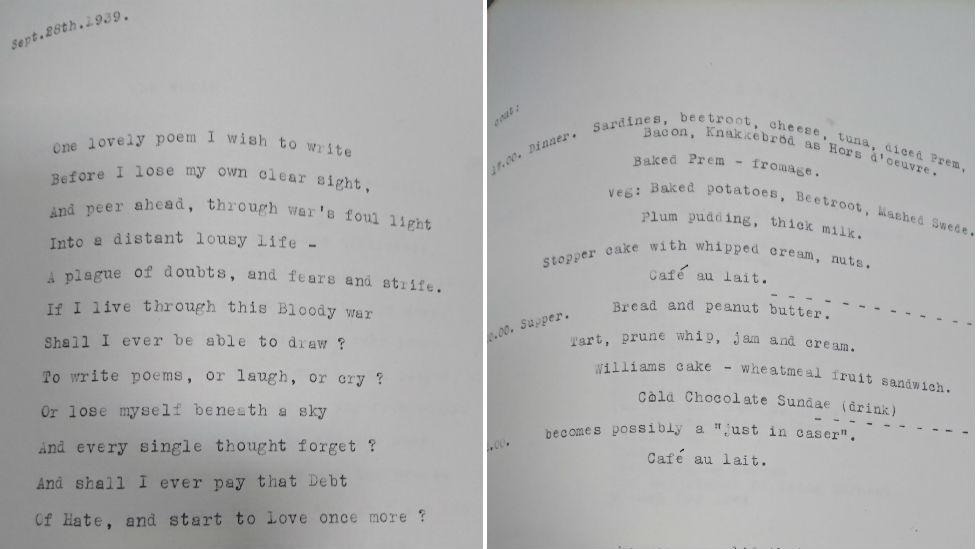

The diary includes war poetry written by Mr Zillessen and details of an improvised "feast" menu inside a prisoner of war camp as the conflict was approaching its end

Writing in his diary about the journey, part of the Long March of 1945, Flying Officer Zillessen said: "Filthy weather, wet drizzle and wind, we wait for hours in this.

"God knows what the after-effects of all this will be."

The diary reveals he was moved to Milag und Milag Nord, a PoW camp complex in northern Germany, with the pilot escaping the Nazi guards in a forest when the prisoners were moved on again.

"In a few moments the guard was looking the other way, we leaped behind the tree and ran," he wrote.

"The roaring of our breathing, the cracking of the dead branches and the pounding of our feet - it seemed to me as if the whole world would hear us."

Tim Zillessen, Marcel Zillessen's son, has visited the former site of Stalag Luft III for the first time ahead of the 75th anniversary of the mass escape

Mr Zillessen travelled to the site of Stalag Luft III shortly before the 75th anniversary to see where his father had been held.

He said: "Much changed after the war in the sense that it freed his mind, he was no longer materialistic and he didn't worry about the things that we would today.

"It must have been overwhelming for him at the end to be able to walk away a free man and alive."

- Published12 March 2019

- Published27 March 2019

- Published15 February 2019