Infected blood scandal: Tainted medication was kept in family's fridge

- Published

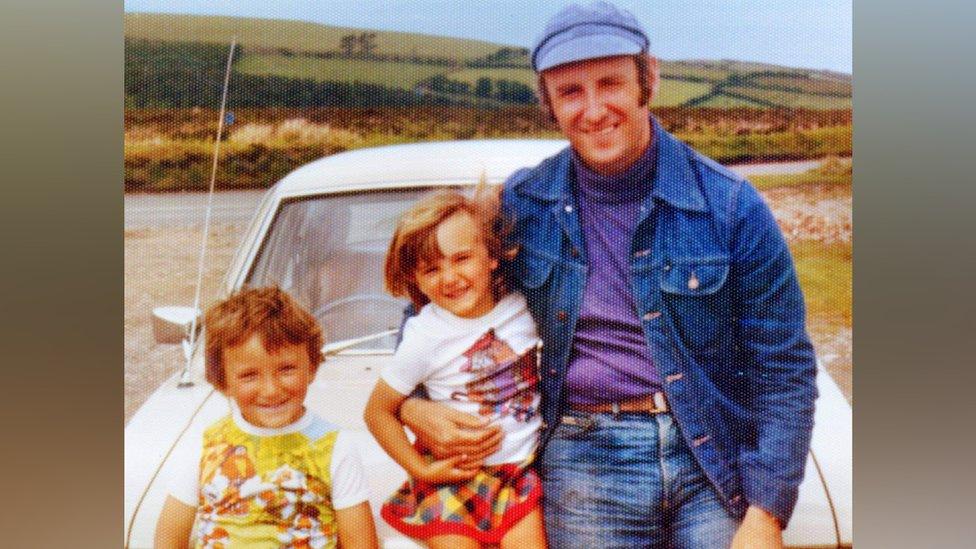

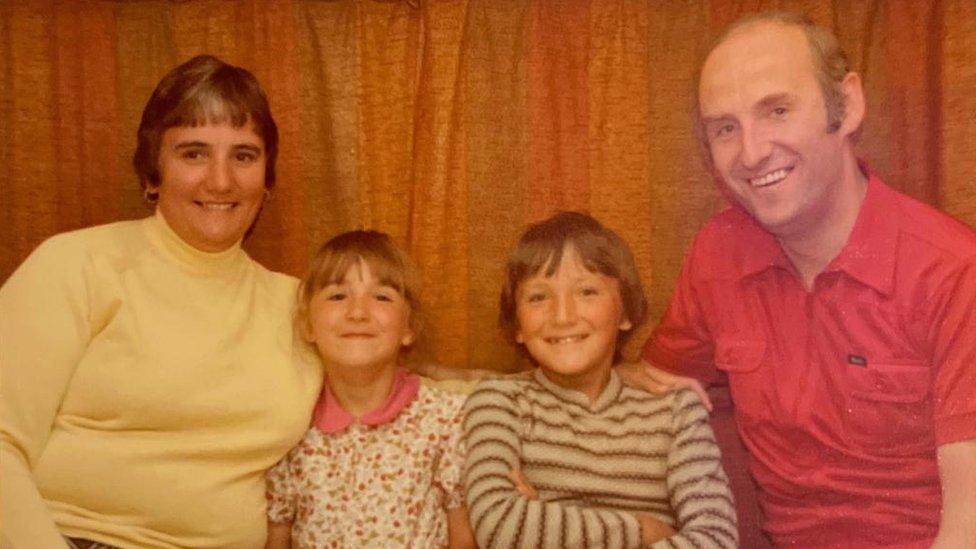

Jack Edwards had two young children, Louise and David, when he died of Aids-related illnesses caused by infected blood

As a child, Louise Edwards thought nothing of seeing vials of blood plasma in her family's fridge.

Every couple of days, her father Jack would take a bottle from the salad drawer and inject its contents into his body.

The vials contained Factor VIII, a potentially life-saving treatment for his haemophilia. But the same medication would ultimately lead to his death.

His family, from Leeds, would come to learn some batches of the clotting agent given to Mr Edwards had been contaminated with deadly diseases.

Mr Edwards was infected by doses tainted with hepatitis C and HIV. He died of Aids-related illnesses in 1985 at the age of 47.

His daughter, who was only 12 at the time, told the BBC it felt like her "world had ended" when she lost her father.

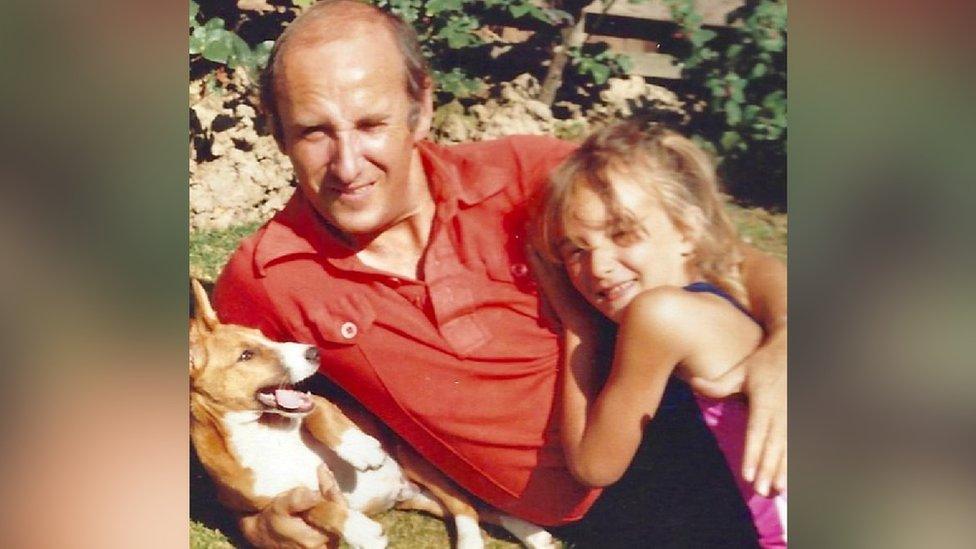

Louise Edwards was 12 when her father Jack died of Aids-related illnesses

"I was a complete daddy's girl. Wherever my dad went, I was usually two steps behind him," Ms Edwards said.

The 50-year-old added: "He was a proper family man who would do anything for his kids.

"When he died, there was a massive hole left and it's never been filled."

Mr Edwards was one of more than 30,000 NHS patients who were infected with diseases from contaminated blood products and transfusions during the 1970s and 1980s.

The scandal has led to the deaths of an estimated 2,900 people in the UK.

Ms Edwards said she still "can't comprehend" the events which caused her father to die.

Louise Edwards said her father's death "should have been prevented"

Mr Edwards, a warehouse foreman who also had a young son, David, with his wife Margaret, began receiving Factor VIII from St James's Hospital in Leeds to treat his haemophilia in the 1970s.

Due to a shortage of blood supplies, the UK government imported Factor VIII from the US, where much of it was made from blood bought cheaply from high-risk donors such as prison inmates and drug users.

Whole batches of the treatment - which were not initially screened for infections - were contaminated with diseases.

On 20 May, a public inquiry will publish its findings into what has been called the largest treatment disaster in the health service's history.

Ms Edwards, who gave evidence to the inquiry, said she hoped the report would "finally give us answers" about "why it was decided it was acceptable to put people's lives at risk".

She added: "I lost my dad and we lost so many people.

"It could have been prevented. And it should have been prevented."

Jack Edwards was never warned Factor VIII could expose him to infections

Ms Edwards said stigma around HIV in the 1980s meant she felt unable to publicly grieve her father's death.

She added her father was never warned Factor VIII could put him at risk.

"It always lived in the bottom of our fridge. It was completely normal," she said.

'Miserable and ill'

Sue Harrison, 74, from Sheffield, was injected with Factor VIII during a hospital test in 1976.

The check - for Von Willebrand disease, a blood disorder her mother carried - was negative and she received no further contact from Sheffield Royal Infirmary.

Thirty-two years later, after a routine blood test in Cyprus, she learned she had hepatitis C.

Thousands of people were infected with diseases by contaminated batches of Factor VIII

Mrs Harrison said she and her husband Trevor had bought a "dream" holiday home in northern Cyprus as part of their retirement plans.

But after the test result she was branded an "undesirable immigrant" and forced to leave the country, which does not grant residence to anyone with certain diseases, including hepatitis C and HIV.

She said: "I had to hand my passport over to the police and they advised me and my husband to get a flight out as soon as possible because otherwise the army would take me.

"That had huge ramifications about my own self-worth and self-confidence.

"I felt dirty, inside and out."

The former nursery teacher added she initially had no idea "how I could have even had hepatitis C".

Sue Harrison was forced to leave Cyprus because she had Hepatitis C

Mrs Harrison has been clear of the virus since 2010 after enduring more than a year of treatment which she said left her "feeling completely miserable and ill all the time".

"I was feeling so ill I did say to my husband, 'I won't kill myself, kid, but if I go to bed and go to sleep and never wake up again, it'll be fine,'" she told the BBC.

Mrs Harrison gave evidence in person to the inquiry in 2019 and said she wanted to speak out for people who could not.

"I've met a number of people in support groups who have been instrumental in helping me get through the worst of times," she added.

"I want to speak out on behalf of that community. Children who have lost parents and parents who have lost children. Which should never, ever have happened. The government, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, had the power to stop all this and chose to save money, not lives."

'Absolutely horrific'

About 26,800 people were infected with hepatitis C through blood transfusions following childbirth, surgery or other medical treatment between 1970 and 1991, according to the inquiry.

By 2022, an estimated 1,820 of those patients had died as a result.

Norman Revill, from York, was infected with hepatitis C during a blood transfusion after an accident in 1983 and said it had been "absolutely horrific" to see other patients "die around you".

While he is now clear of the virus after 18 months of gruelling treatment, the 66-year-old said the impact on him had been "absolutely devastating" both physically and mentally.

Norman Revill said watching other patients die around him had been "devastating"

He told the BBC: "Above all one of the things that really has affected me is the mental anguish I've felt when people around me have died. I think to myself, why have I not?"

Mr Revill added: "I want everybody to be aware of what a tragedy this has been, I want everyone to understand how poorly it's been handled over the last 50 years - the pain and the suffering and the heartbreak that so many people have gone through."

'Appalling tragedy'

The government has been widely accused of dragging its feet over compensation to people affected by the infected blood scandal.

The Haemophilia Society said a further 100 victims had died since the inquiry's chair, Sir Brian Langstaff, told ministers in April 2023 to "act quickly" to set up a compensation framework.

The government has previously said it would be "inappropriate" to consider final payments ahead of the inquiry's full report but last week announced plans to establish an independent compensation body.

A government spokesperson said: "This was an appalling tragedy, and our thoughts remain with all those impacted.

"We have consistently accepted the moral case for compensation, and that's why we have tabled an amendment to the Victims and Prisoners Bill which enables the creation of a UK-wide Infected Blood Compensation Scheme and establishes a new arms-length body to deliver it.

"We will continue to listen carefully to those infected and affected about how we address this dreadful scandal."

Follow BBC Yorkshire on Facebook, external, X (formerly Twitter), external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to yorkslincs.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

Related topics

- Published18 April 2024

- Published14 April 2024