Frank Whittle: The underrated British hero who built a jet engine

- Published

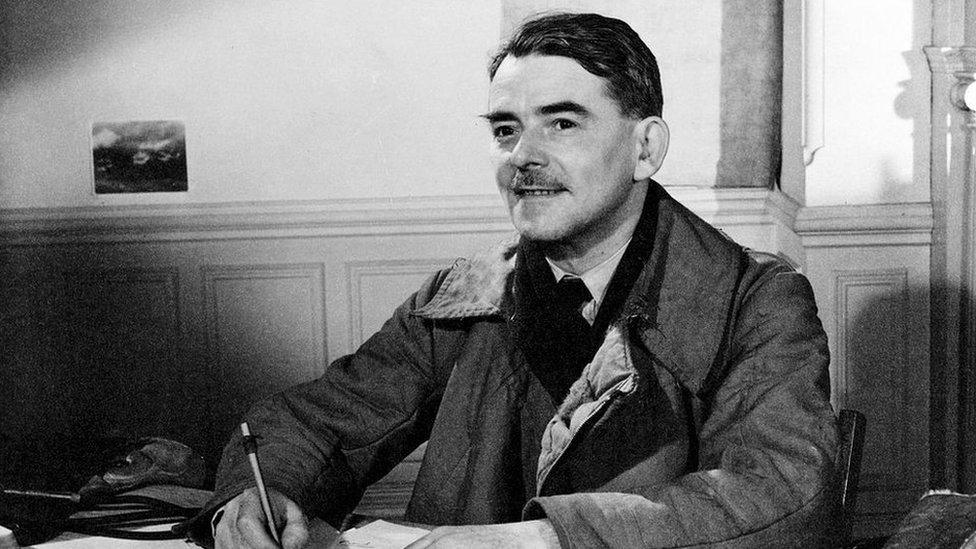

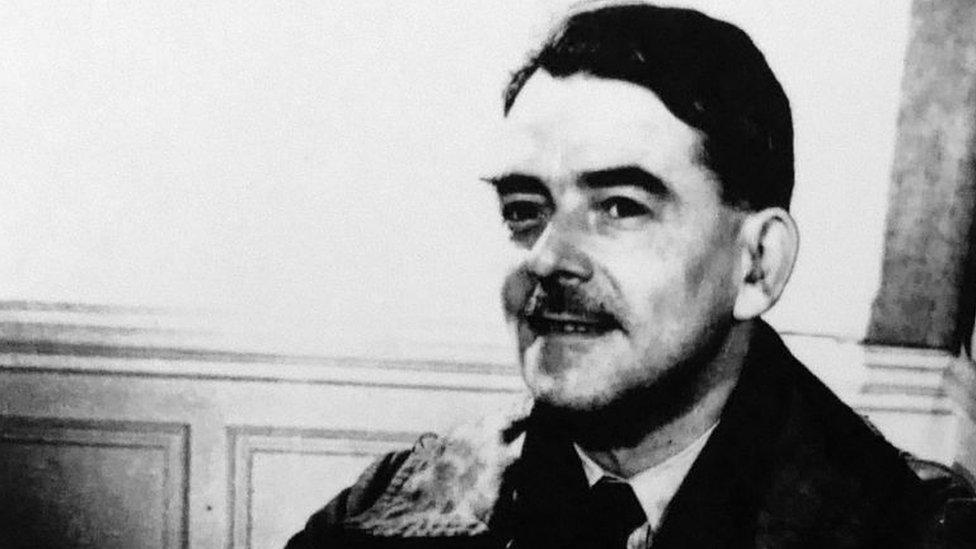

Whittle became frustrated with the government during his jet development

Eighty years ago, a piece of world-changing technology emerged from a semi-derelict garage in Leicestershire - the world's first viable jet engine. But as Frank Whittle's invention took to the skies it prompted a flurry of questions within the British establishment. Had the project been neglected - and was its emergence too late to change the shape of World War Two?

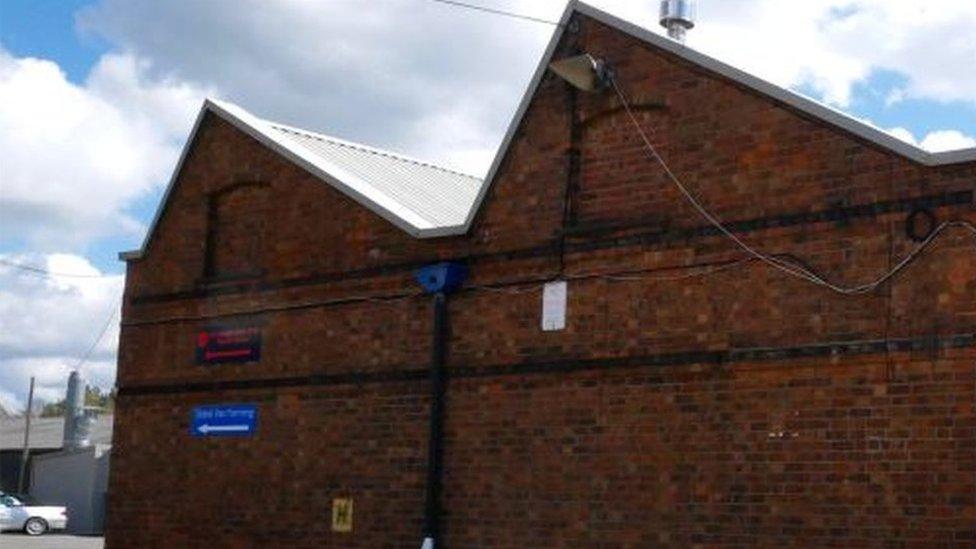

An industrial estate on the edge of a market town is an incongruous place to find a Grade II-listed building.

Lorries rumble past an ordinary-looking, red brick office, that can be overlooked by passers-by.

In many ways, this is only too appropriate. For while this building saw the development of an invention that changed modern travel, some would argue the achievement was sidelined for far too long.

Back in the 1930s, before the construction of the nearby M1 motorway, the Ladywood Works in Lutterworth was surrounded by farmland and it was a top-secret location for the development of the world's first production jet engine.

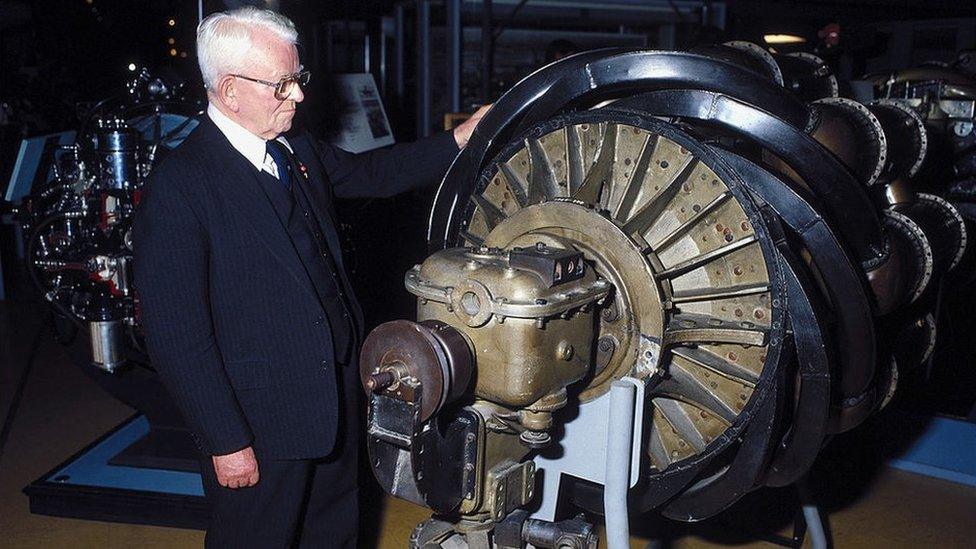

Whittle's engine is on display in London's Science Museum - but some question whether his recognition is as widespread as it should be

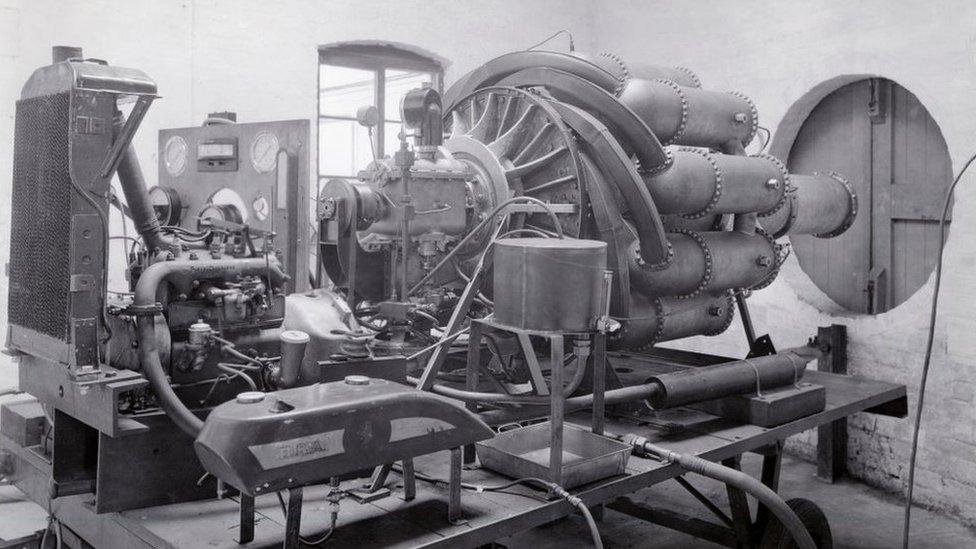

Here a team of bright young men and women fine-tuned and tested an engine known as the W1.

At their helm was Frank Whittle, a maverick Midlands man who had powered his way through an RAF apprenticeship and a Cambridge University engineering course to design something many found unthinkable at the time - an engine for a plane that would travel faster and higher than any previous aircraft.

"I think he's a very underrated British hero," said Duncan Campbell-Smith, historian and author of one of the surprisingly few Whittle biographies, named Jet Man.

"It's a bit of a travesty."

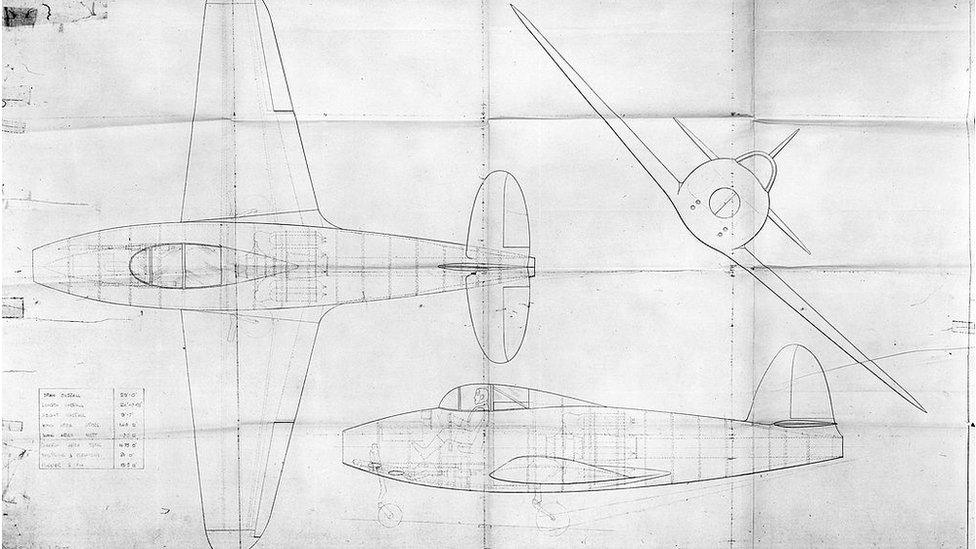

Preliminary drawings for the first allied jet aircraft

Mr Campbell-Smith believes the authorities in the 1930s were slow to back Whittle, partly due to his working class roots - the fact he was not part of the British establishment.

But, crucially, he said, they failed to recognise they were dealing with a man whose thinking was considerably more advanced than their own.

"Whittle's jet engine design was a paradigm shift from the piston engines that were used in aeroplanes until that point," he said.

"To understand a jet engine required a different understanding of aerodynamics and thermodynamics. A lot of very distinguished British engineers could not get their heads around that.

"In a way, you can understand the civil servants' failure to grasp the seismic importance of this shift."

Whittle originally pitched his idea in 1929 but the government did not take him up on it

Whittle had originally pitched his idea for a jet engine to the government back in 1929 but it was rejected.

Cash-strapped, he allowed the patents to expire in 1933.

However Whittle's son Ian, himself a former RAF man, believes the failure to take his father seriously was a missed opportunity.

"It's all conjecture, of course," he said. "But had the authorities sat up and taken notice, then we could have had RAF planes with jet engines in operational service and it might have given Hitler something to think about."

Whittle managed to find private backing for his scheme prior to the war

Whittle did manage to find private backing, setting up a company named Power Jets.

Mr Campbell-Smith believes the timing of World War Two proved unfortunate, with the government taking over the reins of a project believed important enough to be given top-secret status, but not enough to prioritise during the emergency of a possible invasion.

"To the civil servants, the jet was a distraction from the life-and-death situation of the war," said Mr Campbell-Smith.

"The emphasis was on producing more engines for Spitfires and Hurricanes."

Testing the W1's predecessors could be a dangerous business for Whittle and his Lutterworth team

In 1940, the Air Ministry decided to award all production contracts for Whittle's jet designs not to him and his Power Jets team, but to auto manufacturer Rover.

According to Dr Seb Ritchie, deputy head of the air historical branch of the RAF, the government had few options.

"Whittle was an outstanding scientist and mathematician and a great engineer but I can't see how he could have managed his own industrial enterprise," he said.

Today the Grade II-listed Lutterworth warehouse is home to a printing firm which says it is proud of the history behind the building

However Mr Campbell-Smith said Whittle became increasingly frustrated with the situation.

"Every meeting with the government was like wading through treacle, with Whittle trying to persuade them to build the engine the way he wanted it," he said.

"Rover were constantly amending [Whittle's] design and failed to fly a single engine."

Whittle, who was born in Coventry, had to watch the destruction of his hometown

As Whittle and his young family stood outside their Warwickshire home to witness the November 1940 bombing raid on Coventry, he was in despair.

"He was born and bred Coventry," said Ian. "It was awful for my father.

"I remember standing with the rest of my family in the garden. I was wearing my siren suit - a kind of snuggly, one-piece overall. I could hear the German bombers overhead - they had quite a distinctive sound. The sky lit up with the bombs falling."

Ian (right), pictured here with his brother David and his parents said his father's health deteriorated under the stress of developing the jet

The stress had a deleterious effect on Whittle's health.

"I remember him turning from a very jolly chap into somebody who became rather unwell," said Ian. "Mother used to have to look after him and, of course, he wasn't able to tell her anything [about the jet] due to the secrecy surrounding it."

His work was, on occasion, a frightening business, the test jet engines emitting startling noise levels and large pools of fuel that would catch fire.

"The strain on the man must have been intense. [Later] it drove him to a breakdown," said Mr Campbell-Smith.

"Partly that was the strain of working out how the engine would work. The mathematics he was doing was groundbreaking. And partly it was the fact he was an RAF man through-and-through.

"It upset him deeply how many men were losing their lives."

The E28 flew briefly on taxiing trials on 8 May 1941 but its first official flight was on 15 May

To add to the pressure, Whitehall had word from Nazi Germany that a jet programme had got off the ground.

In August 1939, a jet engine designed by a young engineer named Hans von Ohain had briefly powered a plane.

"People point out the Germans had flown a jet but it never flew again," said Mr Campbell-Smith.

"Meanwhile, Whittle had achieved almost the impossible - turned a crude, experimental engine into a prototype, fully ready for flight.

"He was practically on his own - it was amazing that he did it. He turned an engine which worked on a bench into an engine that was flight-worthy.

"He had to beg, borrow and scrape together the funds against a constant lack of interest, constant discouragement, constant apathy."

The plane - known as the "Squirt" by Whittle - created history despite its unusual appearance

The design of Whittle's W1 engine is a familiar sight to anybody who has seen a modern jet engine.

"The technology is still used today," said Dan Price, engineering director of ITP Engines UK, which owns the Power Jets name and still operates on a former company site in Whetstone, Leicestershire.

"We have refined Whittle's original ideas but the fundamentals are still the same."

On 15 May 1941, Whittle and a party of interested engineers and RAF colleagues assembled at RAF Cranwell where a short, cigar-shaped plane - known as the "Squirt" - the Gloster E.28/39 - stood on the runway with test pilot Gerry Sayer in the cockpit.

As it took to the skies to complete a 17-minute flight before coming back to land, those present were in no doubt about what it signified.

During further test flights over the next few days, it reached heights of 25,000ft (7,620m) and a top speed of 370mph.

"Technically, it was the proof his engine worked," said Mr Campbell-Smith.

"It showed jet engines were going to fly.

"The people standing around him on that day were in awe. They knew it was a terrific thing he had done."

The plane provided proof jet engines would work

The success electrified Whitehall.

"The shock effect on the British establishment was considerable," said Mr Campbell-Smith.

"It drew attention to just how much Whittle had been neglected. One person who got very excited was Winston Churchill. When he heard about the jet, he was galvanised by it and asked, 'Why don't we produce 1,000 of these?"

Churchill was keen on producing 1,000 jet engines but the project did not develop until the end of the war

Further delays to the project meant Churchill's vision never happened. By the time the jet was developed sufficiently, the war was drawing to a close.

"There is a degree of frustration it took so long to develop," said Dr Ritchie. "But I don't believe the government was in a position to do anything other than hand-to-mouth development.

"A lot of our top secrets, including Whittle's jet design, ended up being shared with the Americans. There was an awareness that Britain had nothing extra to put into such projects."

After the war, Whittle was knighted and moved to the US, where his design became the basis of a burgeoning industry.

Today, some question whether his name has become overshadowed by his invention.

"There are an awful lot of different ways in which he is commemorated but, in terms of how widespread the knowledge of him is, it could be generational - we are more distanced from World War Two now," said Dr Ritchie.

Whittle is commemorated in Lutterworth, where the jet was developed, but Geoff Smith, chair of the town's museum, says he feels he should be more widely celebrated

For some, Whittle's achievement on 15 May was "bittersweet".

"Whittle was the hero of the hour but the flight doesn't lead to a [jet engine] production during the war," said Mr Campbell-Smith.

"The war, in a way, proved a terrible distraction. The government was genuinely alarmed about an invasion and they couldn't begin to think about such an exciting development as the jet engine. That's the significance of the May 1941 flight.

"It's no wonder it shocked people. They were looking the other way, wondering if they had enough traditional aircraft to win the war. They weren't looking at this man with half a dozen cronies in this factory in Leicestershire, building the future."

Follow BBC East Midlands on Facebook, external, Twitter, external, or Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to eastmidsnews@bbc.co.uk

- Published13 November 2015