Devolution battle beckons between London and Manchester

- Published

It's a decade and a half since London had its political voice restored and there is more appetite for change. The dilemma facing any government is how to meet demands for more autonomy while recognising and retaining the capital's role at the heart of the national economy.

The mayor's key powers are over transport, policing and housing.

But the concern remains that London's ability to respond to the demands and needs of a rapidly growing population is hampered by Whitehall's reluctance to let go of the wallet.

The capital's leaders complain that Treasury spending rounds - looking three or four years ahead - don't give the predictability of money and direction which allow them to make serious plans over the longer term.

Greater devolution would allow the ability to plan infrastructure better without relying on Whitehall

The challenges are there for all to see - an acute housing shortage, a lack of school places, a transport system barely managing to cope. But the necessary levers are not available to pull.

More freedom would enable infrastructure demands to be addressed together - brown field sites brought to life by homes and schools and health centres, next to new offices and shops and near stations, trains and bus routes. The idea is that scale and coherence would bring savings and efficiency.

There appears to be momentum behind some of the recommendations of the London Finance Commission, external set up by Boris Johnson and chaired by Tony Travers from the London School of Economics.

Property taxes like stamp duty, council tax (revalued), capital gains tax and all business rate income would be raised and spent in London.

The government has said it wants to shift control "into the hands of local people"

As proposals go, it looks fairly modest. The effect would be to allow London government to determine and keep a 12% share of taxation raised in the capital, compared with 4% now. London's financial leash would remain much tighter than comparable global cities like New York and Tokyo.

Yet it is hard to see how any government will rush in the short-term to relinquish, say, the redistributive tool of stamp duty. A third of the £7bn received in 2012-13 was levied in London.

Three questions get asked a lot about these proposals for more financial freedom:

Would it lead to higher taxes in London?

Would it lead to less money going to the government?

And would it be at the expense of the rest of the country?

On the first, people may point to the experience of recent years in London's boroughs to suggest significant hikes are unlikely. The simple answer, though, is that through the beauty of an elected mayoralty, they will go up or down according to the persuasive powers and credibility of the incumbent.

On the second, the mayor and the commission are keen to stress that it will be revenue-neutral to the Treasury, but only at the point of transfer.

'Rumblings up north'

Over time, London's financial relationship with the rest of the country would change, and less of the tax raised in London would be exported to subsidise public spending elsewhere.

Would that be a problem? Well, much depends on how the rest of the country itself is coping.

And here we need to note that something is definitely rumbling up north.

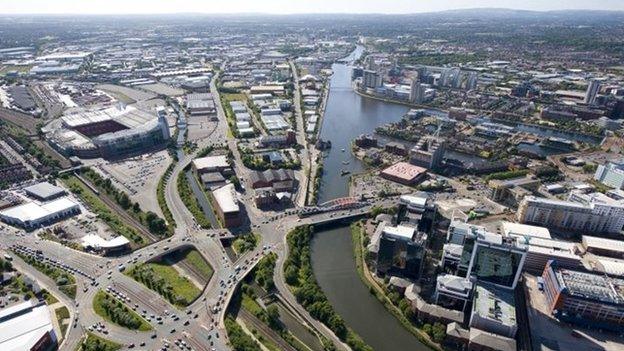

Is Manchester about to become the UK's first genuinely financially-devolved city?

There have recently been ministerial speeches on northern powerhouses, a think-tank report on 'Devo-Manc' and a manifesto for more devolution and localism from the Core Cities Group, external of the country's major conurbations.

This week, the news came that Greater Manchester is to follow in London's footsteps with the creation of an elected mayor.

It all has the unmistakeable feel of a choreography building up to even more devolutionary measures over spending being announced in the chancellor's Autumn Statement.

Some say we're about to see Manchester become the UK's first genuinely financially-devolved city, starting with the freedom to control and allocate the entire £23bn of annual public spending within the metropolitan region.

The first mission would be to close the local fiscal gap by raising the extra £5bn a year in tax receipts needed to balance out that £23bn of public spending. Then, to go into surplus but keep a large chunk of any extra money generated to be invested back into the city. Finally, could there be tax-raising powers offered too?

If this has got a clear economic rationale, it also has a fascinating political dimension. And not just because it looks like a bold Tory plan to try to achieve some sorely-needed relevance in the north.

Is it far-fetched to see this as the turf for a titanic struggle which may come our way quite soon between George Osborne, the 'northern' chancellor with a Cheshire power base, and his equally metro-centric, ex-Bullingdon rival, the mayor of London?

'More Power for London? - a BBC London Special' presented by Jeremy Vine, will be broadcast on Wednesday 5 November 2014 at 22:35 GMT on BBC One #londonwhatnext

- Published5 November 2014

- Published5 November 2014

- Published3 November 2014

- Published3 November 2014

- Published22 July 2014

- Published23 April 2013

- Published5 December 2012