Altab Ali: The racist murder that mobilised the East End

- Published

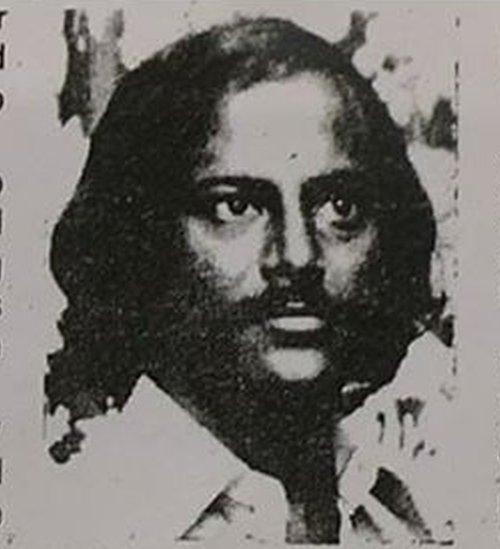

Bangladeshi textile worker Altab Ali, 25, was murdered in 1978 in east London

On the 4th May 1978, a young Bangladeshi textile worker was murdered in east London. It was a racially motivated killing - not unique at the time - but one that awoke a community. Now locals are dedicating a day in memory of Altab Ali.

"When Altab Ali lost his life we didn't feel like we had a choice any more, we had to fight back if we were to survive," says his friend Shams Uddin.

He points at the spot in a Whitechapel park where the 25-year-old was stabbed in the neck, then to a spot just a few metres away where he staggered to before collapsing. It was there that he was found dead.

"I pray for him on the fourth of May every year."

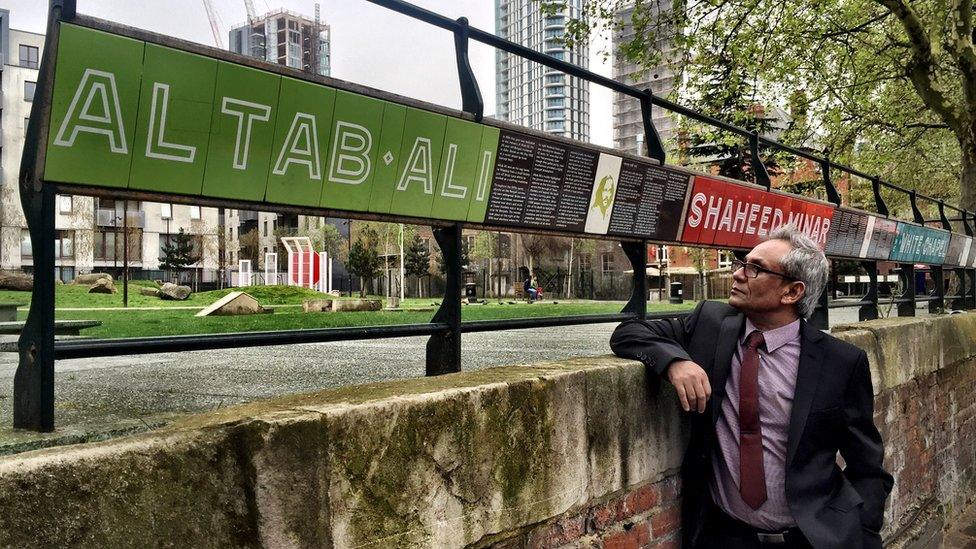

Shams Uddin at the Whitechapel park named after his murdered friend, Altab Ali

Mr Uddin was one of the last people to speak to Mr Ali. He was 18 at the time; the men worked on the same street and were friends who watched wrestling together on a communal television each Saturday.

When the young men bumped into one another that May evening Mr Uddin was walking home after casting his first local council vote. "I was feeling excited, I was a big boy, casting my vote for the first time."

Mr Ali was on his way back from work, carrying bags of shopping. "He told me he needed to go home because he had some cooking to do and after that he was going to go out and vote too."

But Mr Ali did not make it out to vote. He did not even make it home to do his cooking. The 25-year-old textile factory worker was murdered in St Mary's Park.

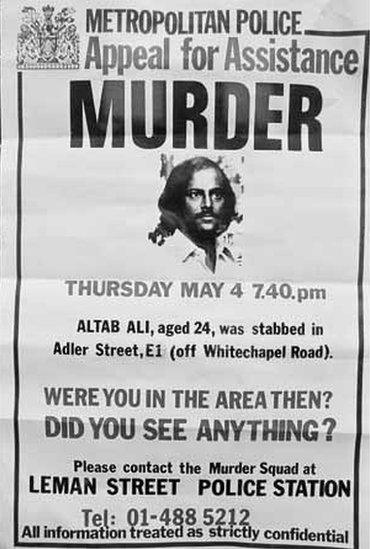

The Metropolitan Police appeal after Altab Ali's murder

Mr Ali, who moved to London from Bangladesh in 1969, was attacked by three teenagers - Roy Arnold, Carl Ludlow and another boy. Arnold and Ludlow were 17; the unnamed male was just 16. The murder was racially motivated and random - they did not know Mr Ali and did not care who he was. "No reason at all," said the 16-year-old boy, when a police officer asked why he attacked Mr Ali.

"If we saw a Paki we used to have a go at them," he remarked. "We would ask for money and beat them up. I've beaten up Pakis on at least five occasions."

The murder marked another ugly moment in the history of race relations in London's East End. Infamously, it was there in 1936 that Oswald Mosley's British Union of Fascists, in imitation of Germany's Nazis, had planned to march in protest at the area's large Jewish population.

Then, Mosley's Blackshirts were halted by more than 300,000 protestors. In 1978, Mr Ali's murder sparked protests again.

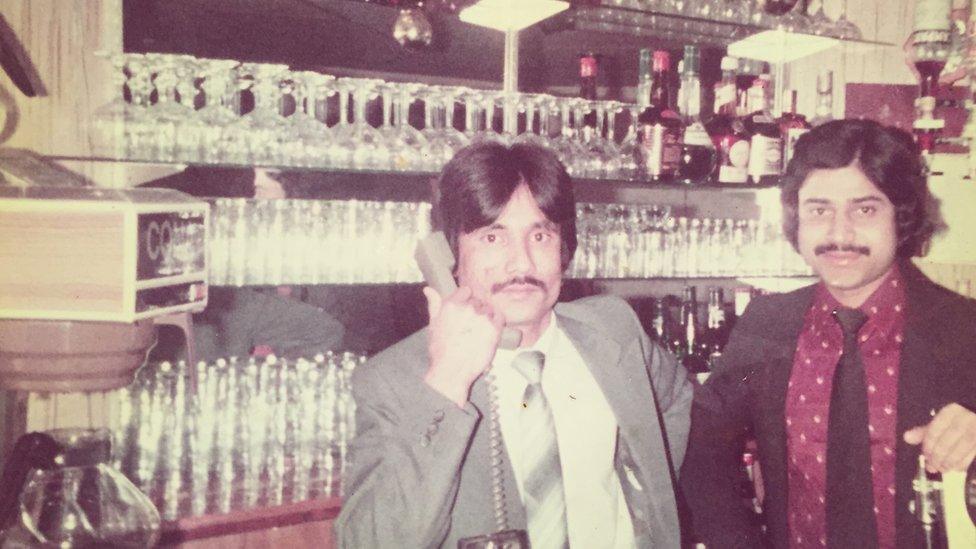

Shams Uddin, pictured here on the left in the 1970s, was one of the last people to speak to Altab Ali

It "came to represent a watershed moment in the self-organisation of the community," according to cultural historian Sander L. Gilman.

Like so many others in the area, Mr Ali was a young male working in a factory, sending money home to support his family. His death was seen by many as a sign that things had to change. The National Front were standing for election in 43 council seats the day Mr Ali was murdered.

Mr Uddin says there had been many other racist incidents that "we just ignored" but the murder was the final straw. "The blood of Altab Ali made us realise we couldn't ignore it, or who would be next?"

"We knew there would be no place for us unless we fought back. So everyone joined together - Bangladeshi people, Caribbean people, Indian people, Pakistani people. Everyone was involved."

Ansar Ahmed Ullah was an activist during the 1970s and 1980s. "At that time, it was very difficult for Bengalis to go out on their own, because you'd often be abused," he says. "If you lived on a council estate your neighbours would be very hostile towards you. They would break your windows, they would push rubbish through your letterbox - basically make your life miserable."

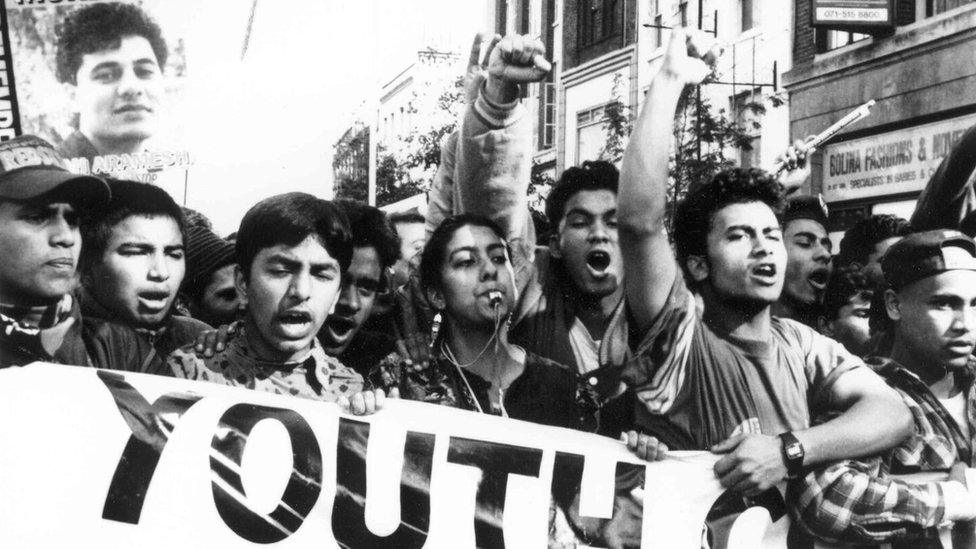

Altab Ali's death was seen as a sign that things had to change, and people of all ethnic backgrounds took to the streets in protest

Mr Uddin says that, as factory and restaurant workers at the time, he and many other Bangladeshis did not feel part of the community or the political system.

But that political silence was coming to an end. Ten days after Mr Ali's death, about 7,000 people marched behind his coffin through central London, calling on the government to address racism in east London. They marched to Hyde Park, Trafalgar Square and to Downing Street.

Shams Uddin recalls the chants of "Black and white, unite and fight" as the large crowd moved through the streets.

"One of our community leaders told us that, if we killed racism from the political ground, it would automatically die on the streets, so we took Altab Ali's coffin to 10 Downing Street."

Change was far from immediate. In June 1978, just a month after the murder, another Asian man named Ishaque Ali was killed in a racially motivated attack in Hackney. Not long after, the National Front moved its headquarters to Great Eastern Street, just a short walk from St Mary's Park.

This brought anti-racism groups and the National Front into tense conflict at nearby Bethnal Green, where skinheads would distribute their literature on Sundays. "When they came to Bethnal Green we knew we were very much in danger," said Mr Uddin.

In response, anti-racism campaigners adopted new tactics. According to Mr Ullah, groups of people would camp in the area overnight. "When the National Front came down in the morning they had nowhere to stand or sell their literature."

"Racism was everywhere, not just in London," he added. "I think Bengalis in other towns like Bradford definitely felt inspired by how we had organised and how we were protecting ourselves."

Though the process was gradual, far-right groups lost their influence in east London over the following decade and violent attacks became less frequent. "We weren't able to transform anything overnight, but by the 1990s the intensity and the violence had subsided," said Mr Ullah.

"I think we were able to change the mind-set of the situation, in terms of how the police, councils and the government treated racism." The protests after the murder of Mr Ali showed a community no longer willing to suffer the violence of racists without fighting back.

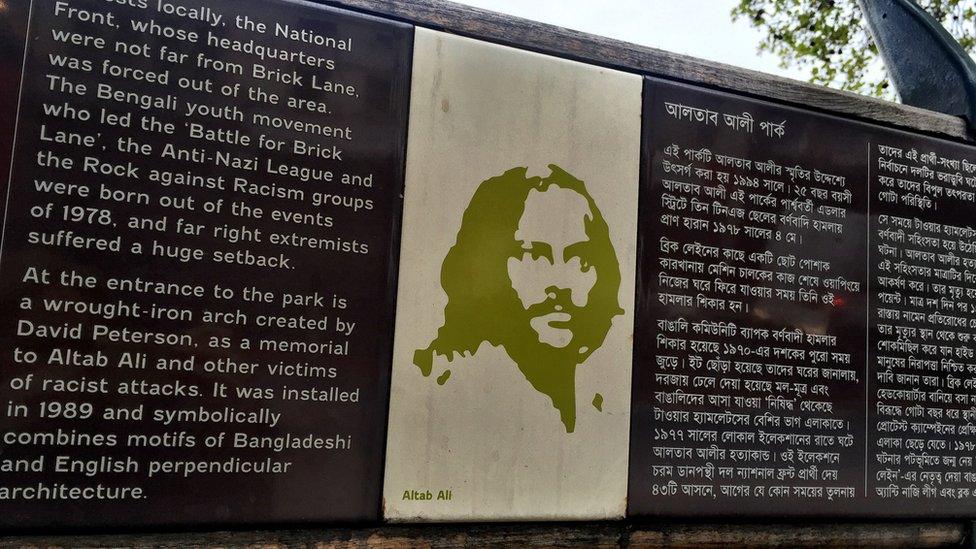

In 1989 the murder scene - St Mary's Park - had a new entrance archway installed, designed as a memorial to Altab Ali, and to all victims of racist violence. Then in 1998 - the park was renamed Altab Ali Park.

Information boards at Altab Ali Park tell the story of his murder and why the park has been dedicated to him

To build on this legacy, John Biggs, the Mayor of Tower Hamlets, announced in October 2015 that the borough would host an annual Altab Ali Commemoration Day; this year is the first.

"We want to keep alive the important message of community cohesion, about standing united against racism," said Mr Biggs. "Altab Ali's murder and the subsequent demonstrations showed people they were not alone in suffering or fearing violence."

Given the attempts of far-right groups like Britain First to gain a foothold in the area, Mr Ullah also believes that Altab Ali Day is a symbol that community co-operation can defeat new forms of discrimination.

"People don't really suffer from violent racist attacks anymore, but racism still exists in different forms.

"You have different ethnic communities, the gay community, the Jewish community, and all these groups are still facing prejudice. The memory of Altab Ali is still very relevant, even if the context is different. It shows the only way to defeat prejudice is for everybody to work together."