'Candy cane' house owner can redevelop it, court rules

- Published

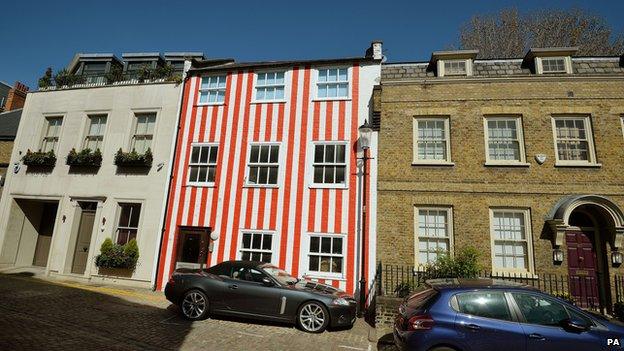

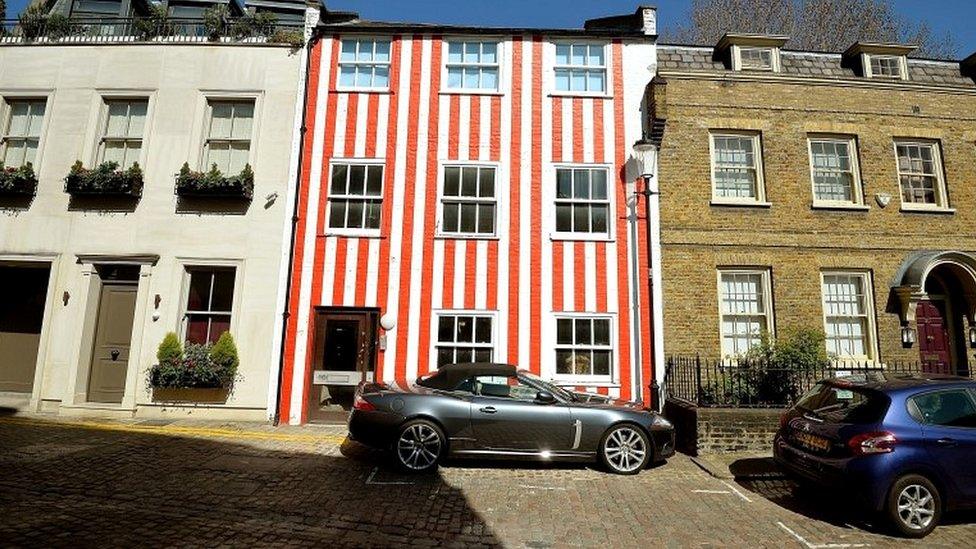

Zipporah Lisle-Mainwaring has been granted planning permission to redevelop the property

A property developer who painted red and white stripes on her multi-million-pound London townhouse has won her appeal to demolish it.

Zipporah Lisle-Mainwaring submitted plans to redevelop the three-storey property in Kensington, west London, replacing it with a new home.

She received planning permission but a neighbour challenged the decision in the High Court last year.

On Monday the Court of Appeal restored the original planning permission.

Paint revenge denied

Ms Lisle-Mainwaring painted the property in red and white stripes after her plans to demolish the house and replace it with a new house and two-storey basement were rejected by the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea (RBKC) in 2015.

She always denied she had painted the property to spite her neighbours who objected to her plans to redevelop the property.

Ms Lisle-Mainwaring was initially ordered by the council to repaint the house after neighbours complained but challenged the order in court winning the right to keep it as it was in April.

Last October neighbour Niall Carroll asked the High Court to quash a planning inspector's decision to grant permission for the property following a fresh planning application.

Legal misdirection

The businessman said the inspector failed to have proper regard to the material consideration of a possible reversion of the property to office use and failed to give adequate reasons for his conclusions.

Mrs Justice Lang accepted that it appeared the inspector misdirected himself in law in his consideration of the possible future reversion.

But three judges in the Court of Appeal restored the inspector's decision on Monday saying there was ample evidence demonstrating it would make no sense, economically or commercially, to resume office use and Ms Lisle-Mainwaring had no intention of doing so.

In the circumstances, no rational decision-maker in the inspector's position could have concluded that the prospect was a material consideration, the court ruled.

- Published24 April 2017

- Published28 April 2015