The Clash: How London Calling still inspires 40 years on

- Published

London Calling was released in the UK on 14 December 1979 and in the US the following month

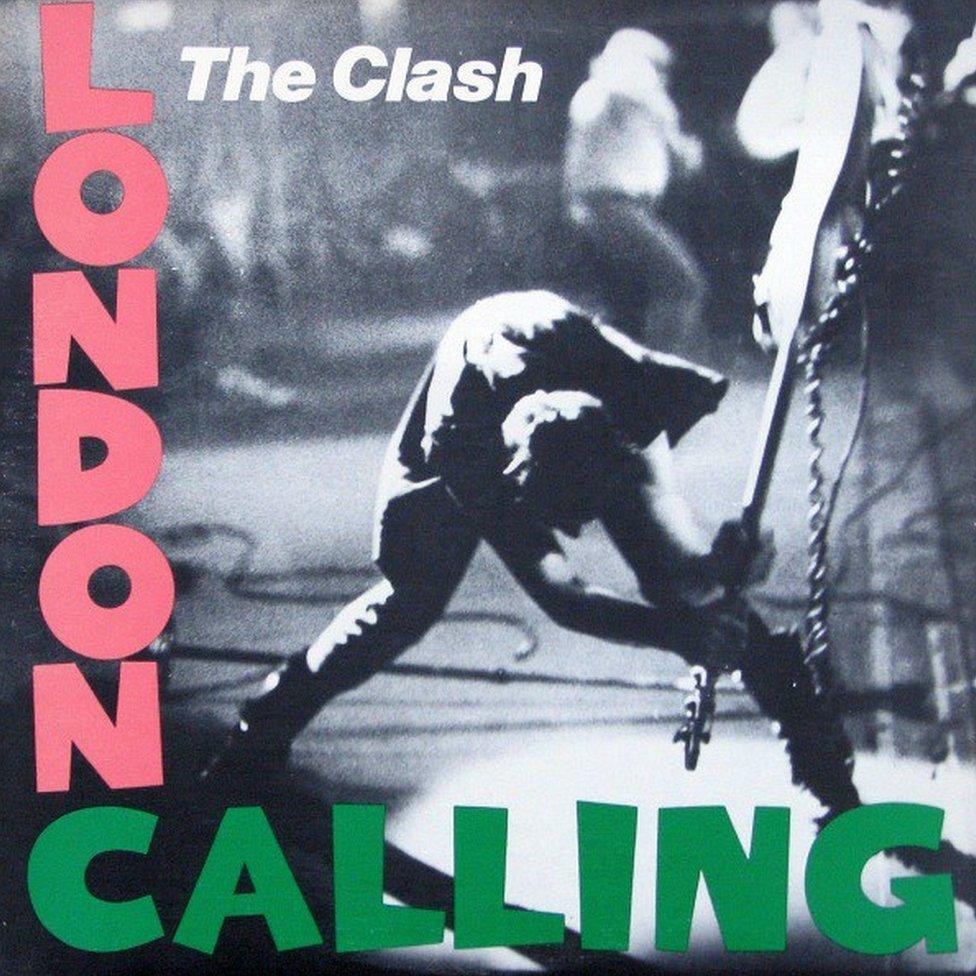

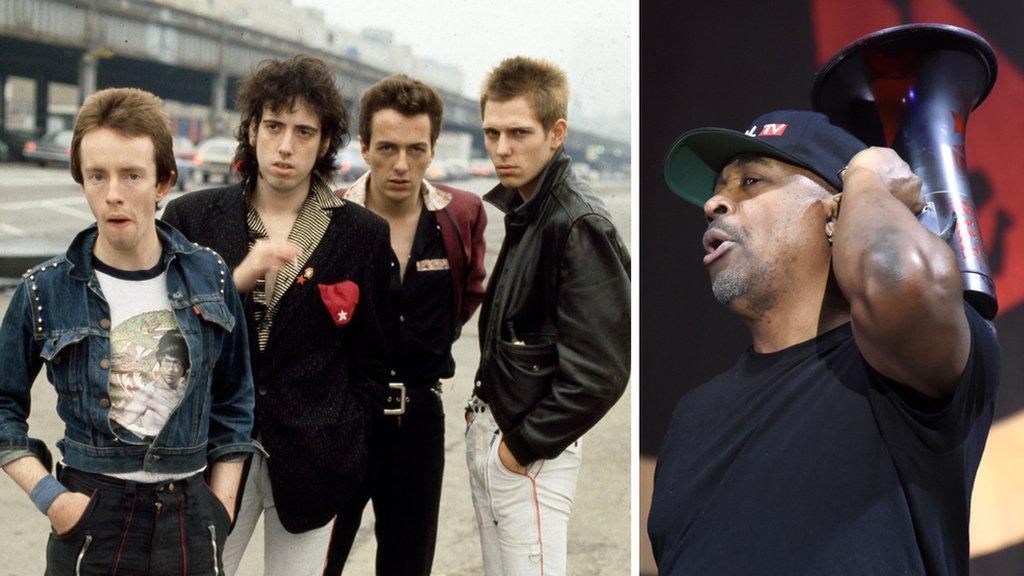

Forty years ago, The Clash's iconic album London Calling and its equally famous record cover featuring Pennie Smith's image of the demise of a bass guitar, appeared in record stores across the UK.

"That bass crashed down and I just thought 'well there's a problem' - The Clash never ever smashed anything - they couldn't afford to."

Johnny Green was at the side of a New York stage on 20 September 1979 as bassist Paul Simonon furiously plunged his instrument to the floor.

"When he started to do this move I nipped on there and said 'what's up Paul?' and his response, rather eloquently, was 'eff off Johnny'."

The move, which Simonon would later reveal was the result of the audience not being allowed to stand up and dance, was captured by Smith. It would go on to become the front cover of one of the most revered records ever made.

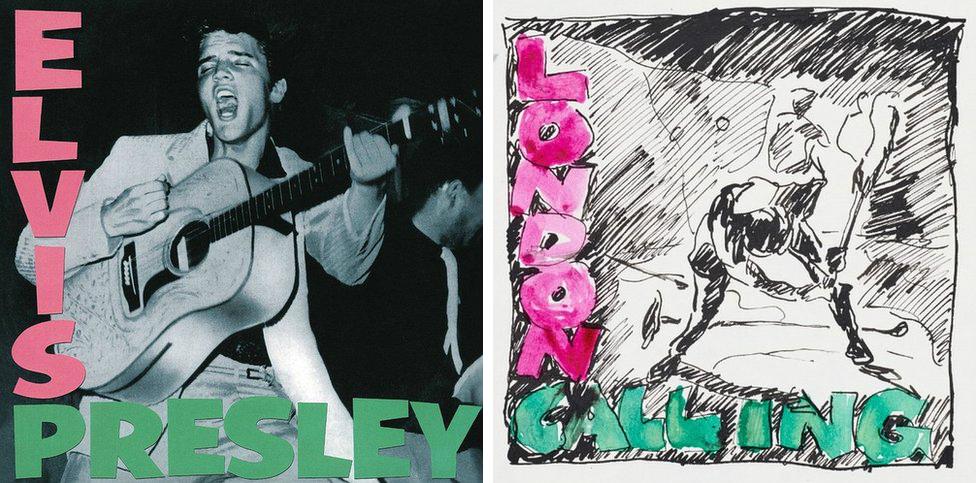

Designer Ray Lowry based London Calling's album cover on Elvis Presley's debut record

Since being released as a double album, London Calling has sold more than five million copies and influenced countless people.

But as Simonon, Joe Strummer, Mick Jones and Topper Headon began the record, things weren't looking too rosy.

"It all seemed washed up to be honest, and that's the story of London Calling," explains Green, who was the band's road manager and one of the few people who saw the record take shape first hand.

The punk rockers had lost their manager along with their original Camden studio. Their record company had also lost interest in the band and songwriters Strummer and Jones were experiencing a lengthy period of writer's block.

Listen to photographer Pennie Smith tell BBC Radio London how she captured the iconic image of Paul Simonon

However, a US tour in early 1979 with the likes of rock and roll veteran Bo Diddley along with the discovery of a new base in Pimlico led to a flurry of creativity.

"They still had something to say and they wanted to say it... so I found this garage in Causton Street, down near Vauxhall Bridge. It was a place where they resprayed expensive cars - dodgy Maltese men in camelhair coats - but it had this lovely room, big and long," Green said.

Influenced by the music they had heard abroad, the band began working "10 hours a day, seven days a week, for three months", successfully incorporating elements of reggae, rockabilly and ska.

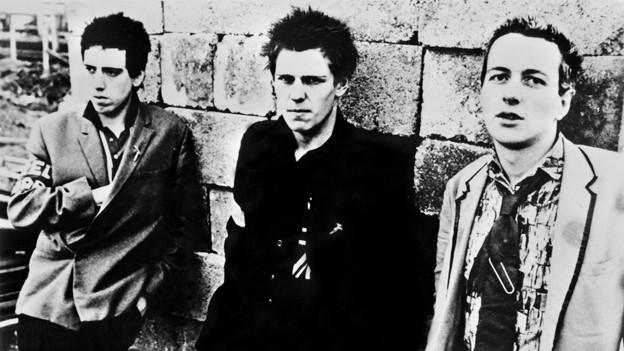

Pennie Smith photographed the band at Wessex Studios during one of the quieter moments

As the fragmentary songs took shape, The Clash relocated to Wessex Studios in Highbury and employed maverick producer Guy Stevens, a man who had a unique method to inspire the punks.

"He'd pile chairs up in a stack and just run at them and knock them over as somebody was playing a guitar lick. I remember him getting a ladder one time and whirling it round and nearly knocking people's heads off," said Green.

"He was a wilder rock and roller than most musicians to be honest... there were times when I had to carry him out of that studio unconscious and into a minicab."

Following the last-minute recording of final track Train In Vain - a song created so late there was not even time to include it on the artwork - the band headed off for another US tour, where the image for the album cover was taken.

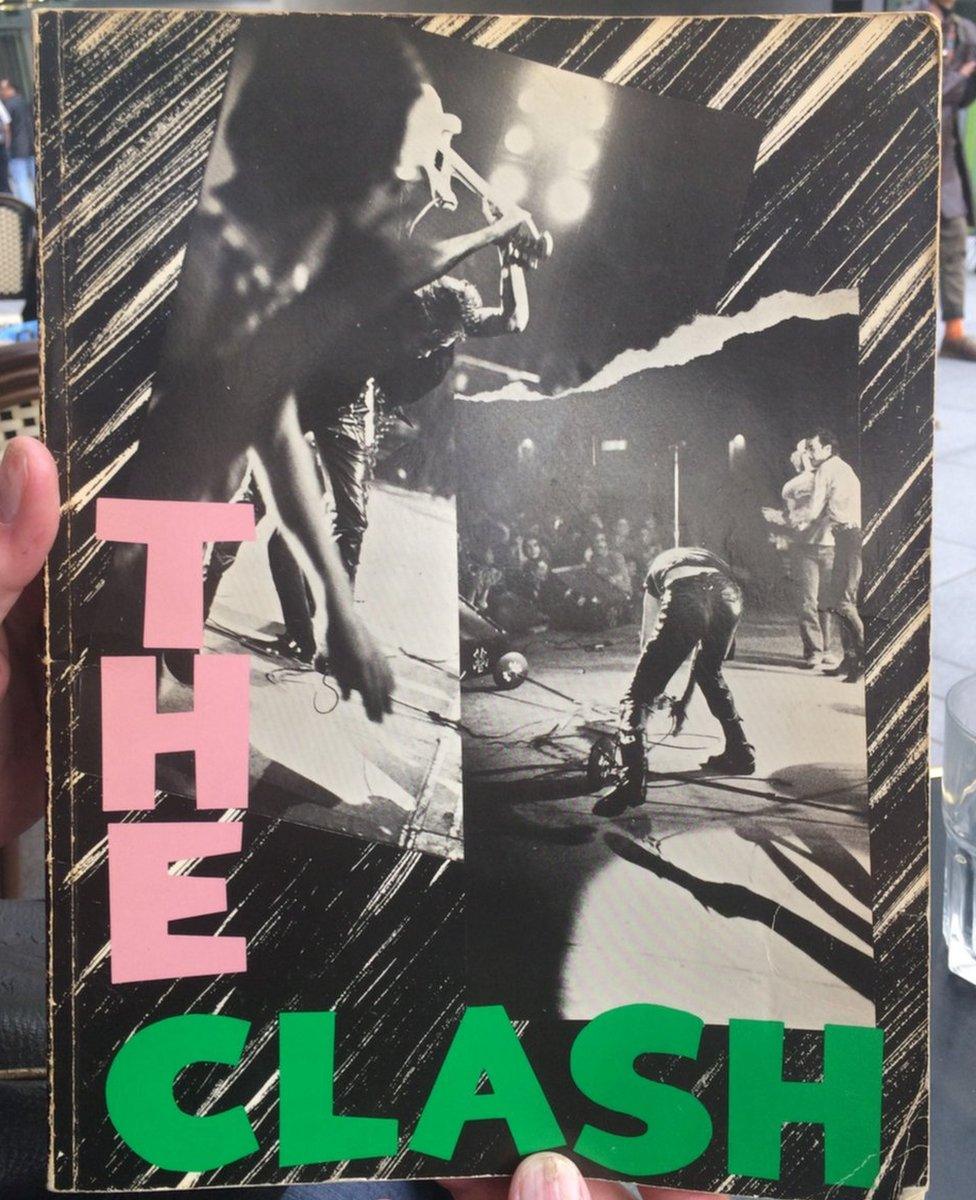

Other photos of Simonon taken by Pennie Smith featured on a rare London Calling songbook

It was on the stage where many first encountered The Clash.

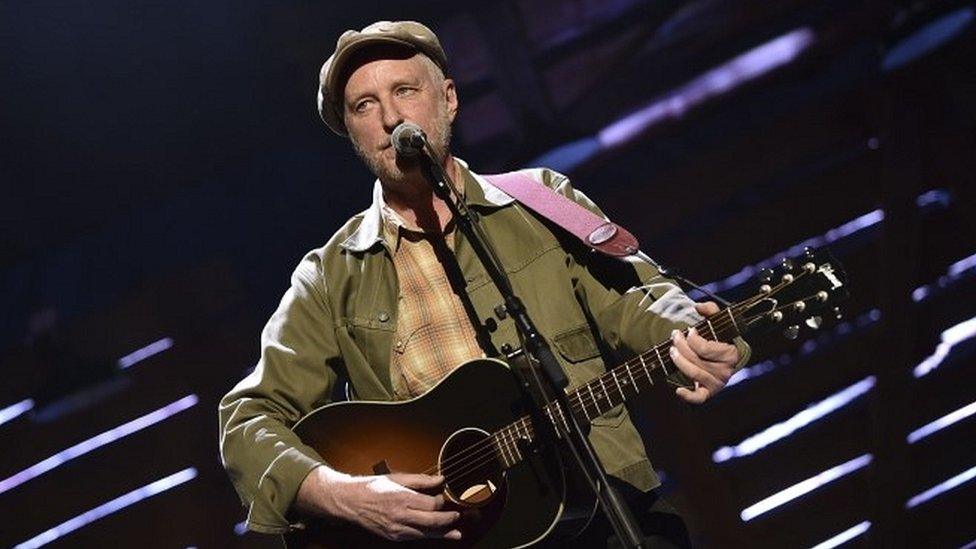

"They were a real force live," said singer-songwriter and activist Billy Bragg. "It was always one of those gigs where you leave with your voice hoarse and ears ringing. The release of energy was just phenomenal."

However, for Bragg what the band had to say was just as important as how they played it.

Take the title track. These days it's used for everything from match-day anthems for Arsenal and Fulham football clubs, to a soundtrack for London on numerous TV shows and films - from Friends to James Bond.

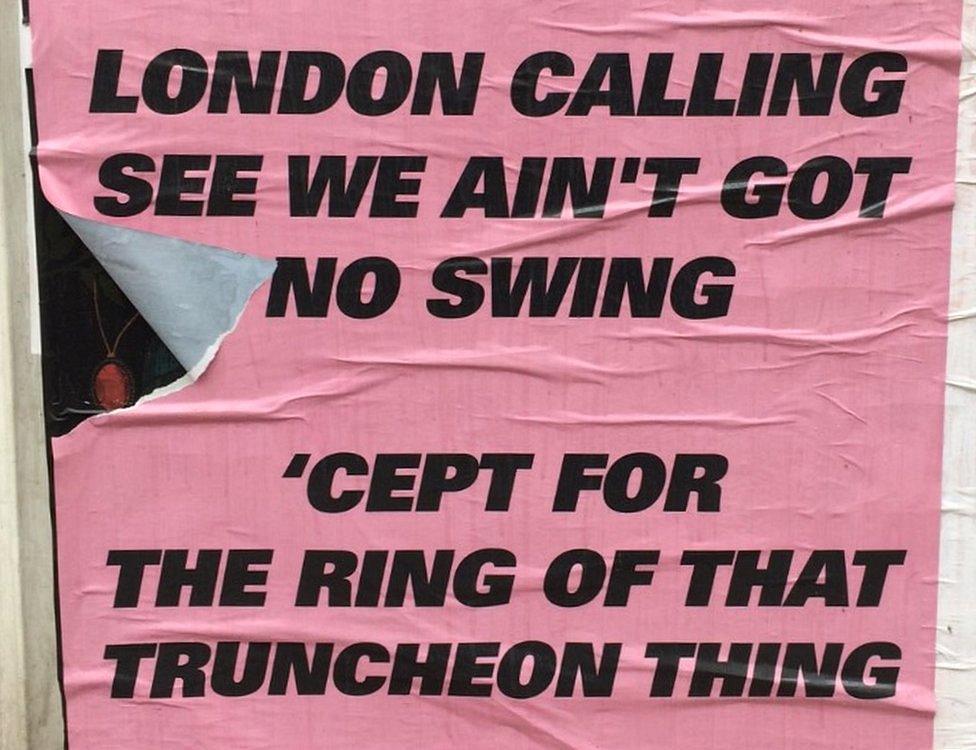

Yet it is in fact a dystopian tale inspired by a news report about how much of the city would be underwater if the River Thames flooded. The lyrics also refer to issues including nuclear disaster, environmentalism, drug abuse and police violence.

London Calling's lyrics recently appeared on posters across London as part of an advertising campaign

The political nature of the album inspired Bragg, along with many others, "to go out and do it for ourselves".

According to Bragg: "If it wasn't for The Clash and their political sensibilities, punk would have just been a haircut and bondage trousers and not a movement.

"For me they were the last great 'music can change the world' band and London Calling was their zenith."

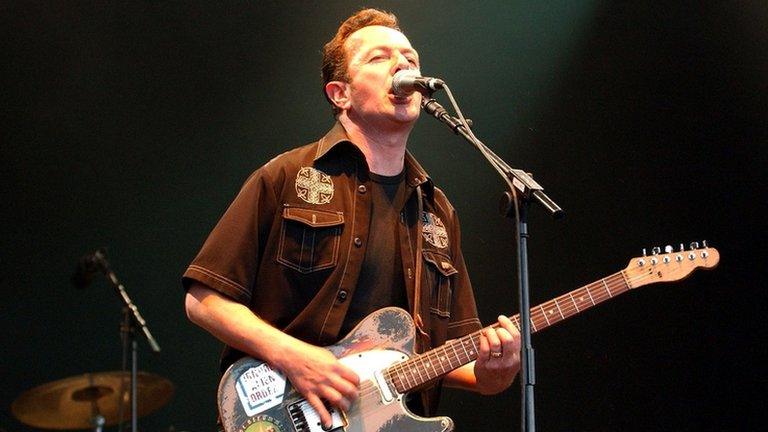

Billy Bragg said he "wouldn't be doing my job" had it not been for bands like The Clash

Given that The Clash explored genres other than punk rock for the record, it's perhaps unsurprising that London Calling didn't just inspire guitar bands.

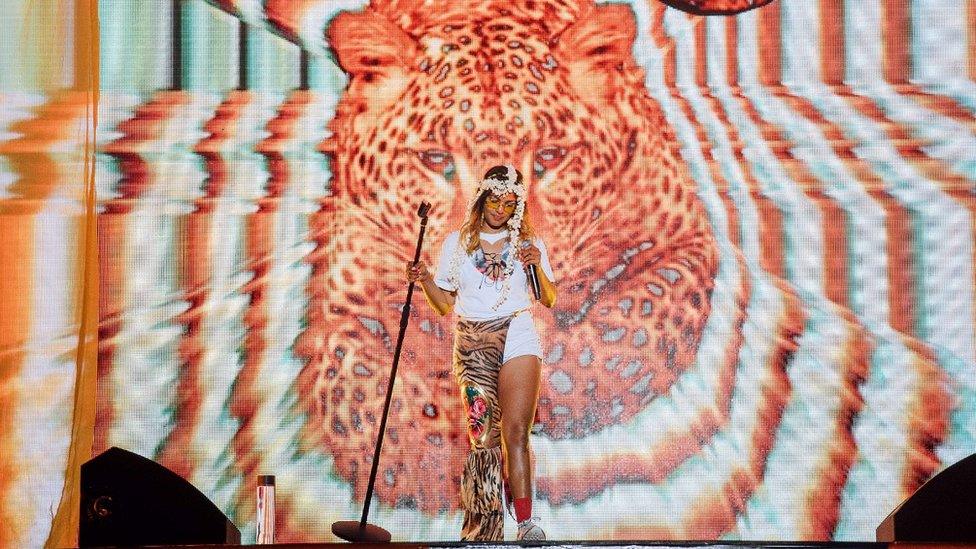

Rapper M.I.A. has spoken about how important the band were for her growing up and references the record in her 2003 single Galang. She also sampled The Clash on arguably her most famous track, Paper Planes.

Across the Atlantic, the band have also been influential. Chuck D of hip-hop legends Public Enemy describes London Calling as "one of the greatest albums ever made", explaining how the four punks "taught us to fight for what really matters - and to do it as loud as hell".

Rapper M.I.A. has described The Clash as a major inspiration for her music

Train In Vain may have been the track that broke The Clash in the US but it was another that caught the attention of Canadian artist Robert Gordon McHarg III.

"Clampdown changed my life. It was a real message to me," he said.

The song, which Strummer initially claimed was about stringent car parking regulations, explores the dangers of an oppressive political system. Its message remains powerful for many, including former US Democrat presidential nominee Beto O'Rourke who quoted the lyrics during a political debate.

Simonon's smashed bass has taken centre stage at a Museum of London exhibition

McHarg has co-curated an exhibition at the Museum of London, external exploring the background of the record and the impact it has had across the globe.

The Canadian believes part of the reason for its continued success is because it is a "global album". He points out that "London calling" was the identifier used by the BBC World Service when broadcasting across Europe during World War Two.

"These guys were drawing it back to the BBC and how the phrase London calling was announced. The record is a call to the world, a global shout-out.

"I lived in Canada and I heard it," McHarg said.

Hannah Kanik rates London Calling as one of her favourite albums

And the record continues to win over fans across the world.

Hannah Kanik, a student at the University of Oregon, said she first "truly listened" to London Calling during her first year of college, having heard it a lot while growing up.

"I listened to the album as a sort of connection back to my family and home life. Now, years later when I listen to it, the record reminds me of my first taste of independence and figuring out how to be my own person and live on my own."

The 21-year-old, who is from Sacramento, California, considers it among her favourite albums and believes it to be "timeless".

"A lot of the themes in the album, like struggling to find yourself or live up to society's expectations for you, are still very relevant today," she said.

Johnny Green co-wrote a book about his time with The Clash called A Riot of Our Own

The man who was there from the beginning said he was surprised both the record and the band remained so popular.

"The Clash exploded like the best firework display you've ever seen in your life... it completely mesmerised you and then it was gone," Green said.

"It really did reach the corners of the world but it's hard to think that would be the case back when we were making London Calling."

The Clash: London Calling is at the Museum of London until 19 April 2020

- Published21 May 2019

- Published2 June 2018

- Published1 January 2015

- Published22 December 2012