Surviving rape: 'I'd watch TV and start feeling sick'

- Published

Martha was living in a house share when she was raped in her own bed by a man she knew.

What followed this appalling betrayal of her trust was a time of anguish, uncertainty and anger.

Here, in her own words, she describes her quest for justice and the effect the rape has had on her relationships and mental health.

'A week later at work I started crying'

I am a rape survivor.

It took me a long time to feel comfortable with that word, rather than the word "victim".

The word feels grandiose; you survive an earthquake or something, you've dragged yourself out of the rubble. But I use it because it is more empowering. Victim means vulnerable, there's no power in it.

Sometimes I don't like the word "survivor" as it sounds like you are more OK than you are. Sometimes I don't feel like a survivor.

In the immediate aftermath of the attack I was shaking a lot. The morning after, I shut down. I went to work and I don't remember anything about that day.

A couple of days later I saw a friend and told him what happened, and said that I'd said 'no' and that he hadn't stopped. He hugged me and said I'd been raped.

Initially I dismissed it out of hand. I had recently gone through a break-up, so that was a much more tangible source of pain. But a week later at work I started crying and I told a friend that I didn't think I was handling the break-up well and that I'd been raped. That was the first time I'd said it.

My friend asked me if I wanted to report it and said for other people she knew, who had been in that situation and had reported it, it had helped give them their power back. That was something that really resonated with me because in that moment, you're so powerless.

'They've got my phone'

We went to the police station to report it.

I ended up being taken to a Sexual Assault Referral Centre in a police van, which made me feel like a criminal. They tried to take some swabs to find DNA evidence that we had sex but they couldn't as it had been over a week.

I know they had to follow protocol, but I was thinking: 'This is pointless, I can tell you I did not sustain any physical injuries. No-one is disputing that. What is in dispute is whether it was consensual.'

The detectives wanted to take my phone because there were some text messages between us. All I could think was: 'Do I need to get a new phone? I haven't told my friends, I haven't told my parents - what excuse in this day and age do I use for having a temporary number?'

Later, a forensics officer wanted to go to my room so I had to tell my flatmates. While the officer was rooting around my room - which was humiliating as my room was a pigsty - my flatmate was standing in the doorway saying 'Martha, I feel sick', and I was thinking: 'Yeah I don't know what to say to you right now, I don't know what to say to me right now.'

I was then signed off work with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). It was then that I thought I had to tell my parents. I didn't really want to but I felt like I had to.

It was the middle of the day. I went home, I told my mum and she told my dad. Later, he turned up at my doorstop wanting to tidy my room. I think it was because it was something he could do for me as he hadn't been able to protect me.

'It's not personal'

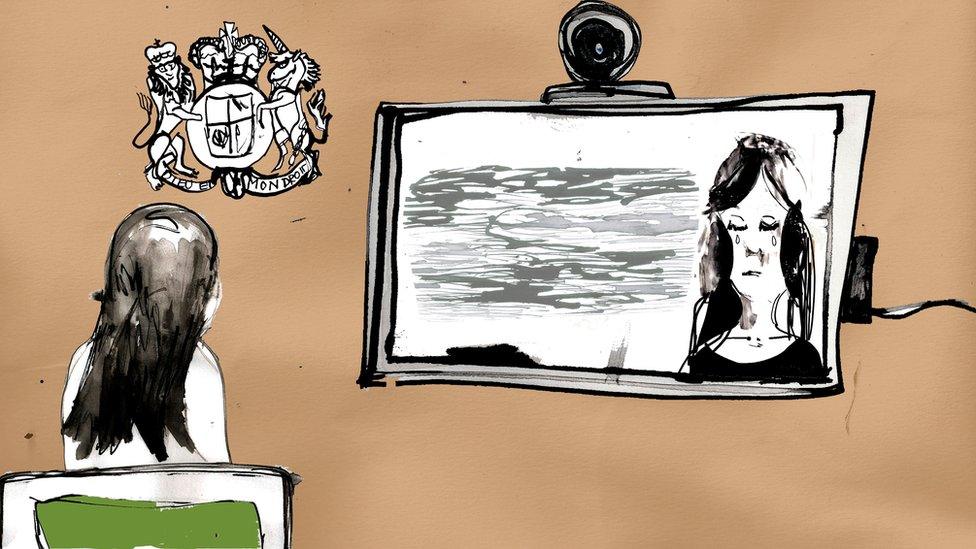

Going to court was tough.

I wanted to pull out but if I did, it would have looked like I was lying. I remember hoping they'd come back and say there wasn't enough evidence so then the choice would be removed.

I had already filmed my testimony so I didn't have to recount everything in court. It was bizarre because it was me filmed 18 months previously and I was thinking: 'I do not know who that person is; that person looks smaller, thinner and a total shell of themselves but they're wearing a jumper I still have.'

When she started to cry, I started to cry.

The cross-examination was an additional, fresh trauma.

The defence barrister was a woman so immediately I thought she was a deserter of womankind. She was patronising.

You understand on an intellectual level she has to essentially spin some kind of story that alleges you are lying. At one point she was trying to argue it was easier for me to say I was raped rather than admit to my friends I'd had casual sex and it wasn't good.

I remember there was this constant focus on what I'd been wearing. It made me lose all my courage and I thought it was going terribly because I couldn't remember if my pyjama top was on or not. In the meantime, the prosecution barrister was doing nothing because there's nothing to object to. So I was in this room full of people, completely defenceless to what feels like an attack.

The clerk led me out and I was physically shaking, I was so traumatised by it.

As we were walking, she turned to me and said "it's not personal". What could be more personal than what had just happened to me? I'll never forget her saying that to me.

My attacker was found guilty and sentenced to four years in prison, two of which were on probation. Two years is nothing - we'd waited nearly two years for the trial.

But I recognised how lucky I was to get a guilty verdict. So few report it and then, of those that do, so few get to trial and, of those, fewer get the guilty verdict.

So then you feel this weight that you can't even complain, because you got the justice, right? That's what we all want. That's why what happens after is so frustrating and angering because it doesn't just go away.

I did it, I stuck my neck out, I reported it, I stuck with it. I sat through all of that crap from the defence barrister and I got the guilty verdict. I got the justice, so legally it is on record that he raped me. So that should be it - I've got my power back. But I don't know if I did.

'This is happening to women everywhere'

My PTSD started to manifest itself again. I'd be watching a TV show or reading a book and there'd be a rape scene and I would start feeling sick, spaced out and wouldn't want to be touched. I felt very on edge and upset, like my nerves were on fire.

I think the perception is that PTSD is getting flashbacks to your own rape, but my brain fixated on other women being raped. Imagine trying to conduct yourself, like have a normal conversation, do your job, do your work, and in your head there's a show-reel of women getting raped. It was horrendous.

Sometimes we don't consider what it means to have someone inside someone else, to be breached in that way. If you're not able to have some control over what's going on underneath your skin, then you've got no bodily autonomy, you've got nothing.

I think it was because I was realising it wasn't just me, that it was happening to women everywhere, all the time. That made it feel completely inescapable and overwhelming. It could happen to me again or to someone I know, someone I love.

I was referred for EMDR (eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing) therapy. The idea is the rapid eye movement you have when you're asleep is part of coding short-term memories into long-term ones. The traumatic memory is stuck in your short-term memory so the aim is to code it into your long-term memory so that it's not so fresh and traumatic.

The therapist asks you to relive the trauma while they sort of start waving their hands in front of your face to force rapid eye movement.

In hindsight I think it did probably help as now it feels like a long-term memory but at the time it didn't feel like it was necessarily helping.

'I was relieved when he was deported'

I remember he got out on Christmas Eve. Merry Christmas to me.

The victim liaison officer said my rapist was being held by immigration separately, but that they were going to release him on bail.

He gave them addresses of places he could go to, but as he was on the sex offenders register a couple of them were rejected as he would be near a school or near an old persons' home - i.e. vulnerable people.

However, the address that did not get rejected was a 10-minute drive from where I was living.

I asked my victim liaison officer why am I - his actual victim - not the ultimate vulnerable person? She said immigration didn't know where I lived and if she told him then he would know where I lived because if they were then going to reject the address, his lawyer would need to know why.

I tried to fall back on to the logic that he would be an idiot to hurt me as he would be suspect number one.

Every possible route out of where I lived to go into central London would have passed through the general area where he was.

The setup was if he saw me he had to immediately get off and call his probation officer and I'm thinking: 'You're thinking about this from a perpetrator perspective, you're not thinking about this from a victim's perspective.'

If you're thinking about this from a victim's perspective you would say, 'OK what if I see him and he doesn't see me?' It's such a flawed arrangement that was presented to me as reassuring.

I think it was under a year before he was deported. I felt relieved, but I also felt I should have felt happier.

'I avoided having a smear test'

One thing I'm thinking about: do I want to have my own children? For a lot of survivors, being pregnant and going through childbirth is a very triggering experience and that never occurred to me - and certainly no-one tells you about that. I'm not pregnant now and we haven't started trying but pregnancy could be 15 years after I'd been raped and that will be a very real and fresh thing for me.

I am OK with telling doctors. During one examination, I had to say to them: 'Look, I am a sexual assault survivor, I can do this but I'm going to need advance notice, I'm going to need you to talk me through what you're doing and why you're doing it.'

I got my letter for my first smear test [since the rape] but I avoided it for so long.

I then found a charity called the My Body Back project, external which specifically looks at cervical screening and STI testing for people who have experienced violence. They were amazing. They guide you through, they have a really experienced doctor who understands, they have a mindfulness person there with you.

The charity has a maternity unit but childbirth is on its own schedule so if I can't access their unit, are the doctors in a hospital going to get it? Are they going to listen?

I don't know what my husband feels about it. It's only really recently I can handle him hugging me from behind, like when I'm doing the washing up, and kiss my neck or whatever.

I hope for my kids that things will be different, because I feel strides are being made with sex education and talking about consent.

I would like to see rape talked about more. I would like to see us not debating consent. I want to challenge what the idea of a survivor is. There are many different types of survivors, because there are many different people.

You know what happened to you, and that's all that matters.

As told to Rebecca Cafe; illustrated by Katie Horwich

If you have been affected by sexual abuse or violence, help and support is available at the BBC Action Line.