Is London's mayoralty in crisis?

- Published

Sadiq Khan was due to stand for re-election in May but it was postponed for a year due to the coronavirus pandemic

The mayor's relationship with central government has endured a very difficult few months and there seem to be further bumps in the road putting questions over whether London's mayoralty is in crisis.

What Dave Hill doesn't know about London politics probably isn't worth knowing. The former Guardian columnist now edits OnLondon, a widely-respected independent website about the capital's political landscape.

Several of his recent articles paint a picture of a mayoralty in trouble, the mayor's hand forced by the government into a series of compromises and surrenders of power in what Mr Hill described as "an extraordinary intrusion on the mayor's autonomy".

Plenty would either disagree and point out that any intrusion is necessary under the circumstances, but Mr Hill's argument is that the government is using the pandemic as a pretext to erode the powers of Sadiq Khan.

'Political lever'

In an unusually strong statement the mayor's spokesperson said Covid-19 was being used "as an excuse to attack and undermine London government to an extent we haven't seen since Margaret Thatcher abolished the Greater London Council (GLC) in the 1980s".

That sentiment was dismissed by a government source who told the BBC "the idea that any government would use the pandemic as a political lever is nonsense".

The roots of it depend who you listen to, but much of it centres around the finances of the capital's transport agency, Transport for London (TfL).

Transport use fell by 60% between early February and the beginning of April, according to the Department for Transport

Control over the city's transport network is one of the few clear-cut genuine powers the Mayor exercises.

But over 70% of TfL's income comes from fares, and its revenue fell off a cliff during the pandemic when passenger numbers fell to levels not seen since the 1800s.

As early as 24 March, the day after the UK entered lockdown, Mr Khan spoke to Transport Secretary Grant Shapps on the phone to explain TfL was spending its reserves at an unsustainable rate of knots - it costs £600m a month just to run the network and it spent its £2.1bn reserves in a matter of months.

Which meant a bailout was inevitable.

In 2019-20 Transport for London earned £4.9bn from fares - 47% of its income

After eight weeks of negotiating, a £1.6bn deal was reached, just minutes before the Commissioner of TfL was required by law to stop the Underground and buses from running the following morning.

Attached to the deal were several conditions which, Sadiq Khan claims, appeared just days before he was required to grind the network to a halt.

It included extending the scope and level of the Congestion Charge; to temporarily suspend free travel for the under-18s and over-60s; and to raise fares.

"TfL has had awful conditions imposed on it by the government," claimed a mayoral spokesperson.

A source close to the government said: "Of course deals are pretty urgent, but the idea that he was bounced into it is ridiculous. He's trying to distance himself from the necessary measures while taking the money."

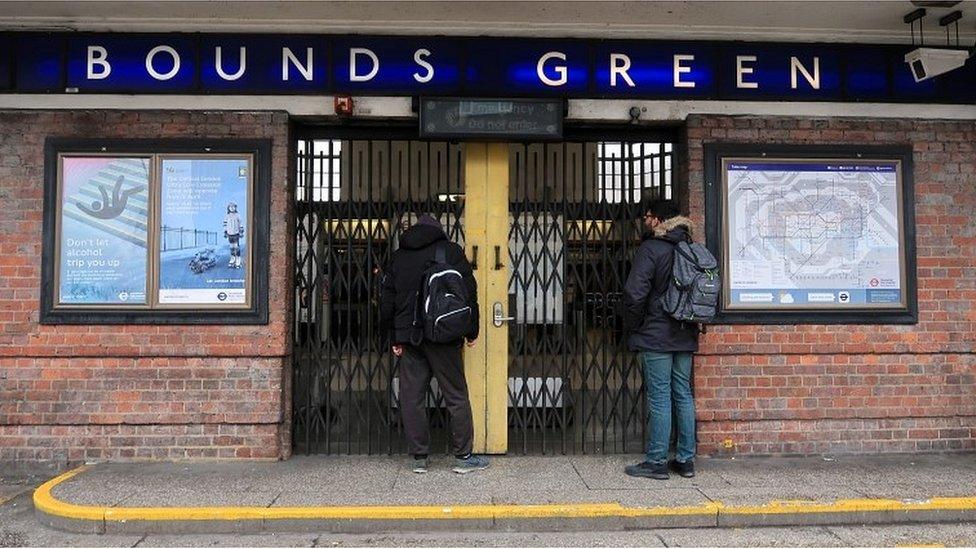

Bounds Green was one of many Tube stations forced to shut as TfL cut back services

Last month the mayor appeared before the Transport Select Committee, telling MPs he thought "negotiations would be slightly easier if I wasn't standing for re-election next May".

The same government source added the mayor "is trying to have his £1.6bn cake and eat it. Who could argue with the scale of that assistance? If he wants to paint it that it could've been rosier for a Tory mayor, it's just politicking."

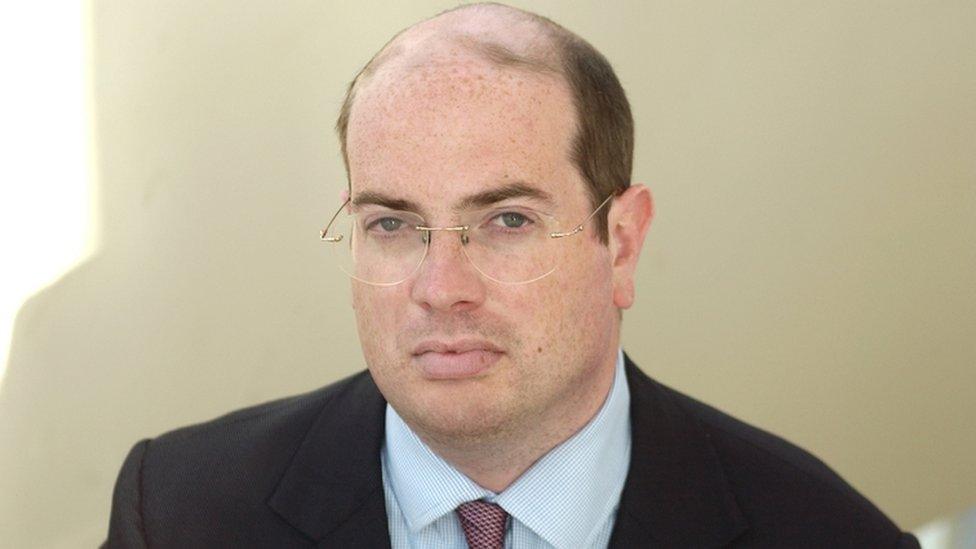

Also attached to the deal was a condition that two government-appointed members sit on the TfL board, one of whom is Boris Johnson's former cycling commissioner, Andrew Gilligan.

Andrew Gilligan worked under Boris Johnson when he was mayor of London

Mr Gilligan's supporters point to his successes in building the segregated bike lanes dotted around the capital, but he is a controversial appointment.

"The thing about Gilligan," says Mr Hill, "is that people who worked with him at the highest levels of Boris Johnson's administration thought he was a complete loose cannon".

All of which sets the scene for October, when TfL will require another bailout.

It seems inconceivable that another deal won't come with more strings attached and, if so, some of the mayor's supporters will likely claim it's a government power-grab, and some of his opponents will claim Mr Khan has been profligate.

TfL and its funding seems likely to be a continuing battleground between the government and City Hall.

It's not just in transport that the government has flexed its muscles. Take the London Plan, which is a planning blueprint for how the capital is going to look in the coming couple of decades.

Councils in London built 2,100 social rented homes over the last seven years - Sadiq Khan had ambitions for 10,000 by 2022

A new plan is published every few years - the latest orchestrated by one of the deputy mayors, Jules Pipe - and the document runs to hundreds of pages, takes years to write, and must clear numerous administrative hurdles before it is signed off by Robert Jenrick, the Communities Secretary in Whitehall.

"It had gone through all the examination," says the London School of Economics' Tony Travers, "and then the government said it would impose its own version of the London Plan on the mayor of London, largely because of a disagreement over housing and planning policy.

"That would be unthinkable in Scotland or Wales."

Mr Jenrick wrote Mr Khan an excoriating letter on 13 March which said the mayor's housing record was "deeply disappointing" and "only serves to make Londoners worse off" and sent him back to rewrite sections.

"You can see the mayor's planning powers being eroded through the back door," Mr Hill said.

"I think Sadiq Khan has shown he's adept at using conflict with the government to his advantage, but will there be anything left of the mayoralty come May?"

The City Hall building has been home to the Greater London Authority since 2002

By May, Sadiq Khan could be preparing to move to a new building. A few weeks ago he announced that City Hall could move from its central London location next to Tower Bridge to a building called The Crystal at the Docklands in east London.

The aim is to save money: some of the mayor's budget comes from business rates and council tax income, both of which have taken a hit during the pandemic, and the Greater London Authority, of which the mayor is a part, pays about £11m a year in rent to the owners of City Hall.

But might moving to east London contribute to a sense that the mayoralty simply isn't as important as it once was?

"It does risk, however accidentally, reinforcing the idea that the mayor is less central to the life of the city than he ought to be.

"I can't think of another City Hall that isn't in the middle of a city," says Tony Travers.

The Crystal was opened in 2012, having been commissioned by Siemens as an exemplar of sustainable design.

It is something Mr Hill agrees with.

"There have been some cynical people saying that it's a rent review happening in public," Mr Hill said.

"But I do think moving would have a diminishing effect. You've been in a bespoke building, next to Tower Bridge, one of the most famous London landmarks. Whatever the benefits of The Crystal, the mayoralty will look shrunken in authority."

The months ahead look set to be a defining one not just for Mr Khan, but for London's 20-year-old mayoralty.

- Published12 August 2020

- Published24 June 2020

- Published14 May 2020

- Published21 April 2020