Damilola Taylor: What lessons have been learnt 20 years on?

- Published

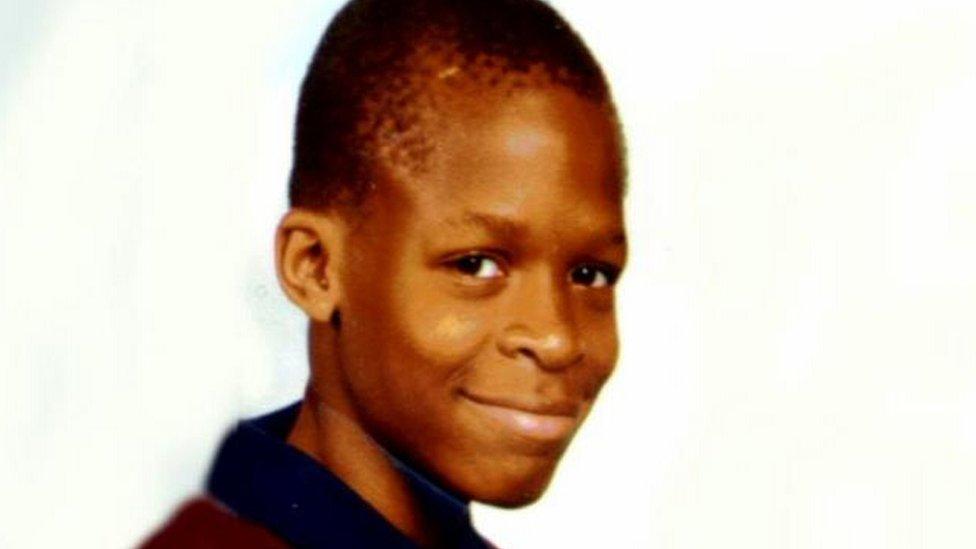

Twenty years ago, 10-year-old schoolboy Damilola Taylor was stabbed in the leg and left to die in a south London stairwell. It took six years and three trials for brothers Danny and Ricky Preddie to be convicted of manslaughter. They were aged 12 and 13 at the time of the killing.

Police say the investigation was hampered by a wall of silence from the local community in Peckham as well as a lack of experience dealing with children in gangs. So what has changed since the shocking killing?

It was a cold and wet evening on 27 November 2000, recalled Rod Jarman, who at the time was the Metropolitan Police's Borough Commander of Southwark.

He had just arrived home from work when colleagues called him to say a boy had been found bleeding to death in a concrete stairwell in Peckham. Damilola had been stabbed in the leg with broken glass.

The scene was even worse than it appeared in pictures that were later splashed on the front pages of the national newspapers, Mr Jarman said.

CCTV showed Damilola on his final journey from the library in Cronin Street

"What you don't get from the pictures is the smell," the former officer said.

"There's all the rotting food, the smell of urine and that whole despair that's just wider - just a horrendous place.

"When [Damilola] was trying to get home to safety he ended up somewhere where nobody should really end up."

Damilola was on his way home from the library when he was attacked.

At about 16:00 GMT - and just a few hundred yards from the safety of his home - he was stabbed in the thigh with a broken beer bottle and left to die.

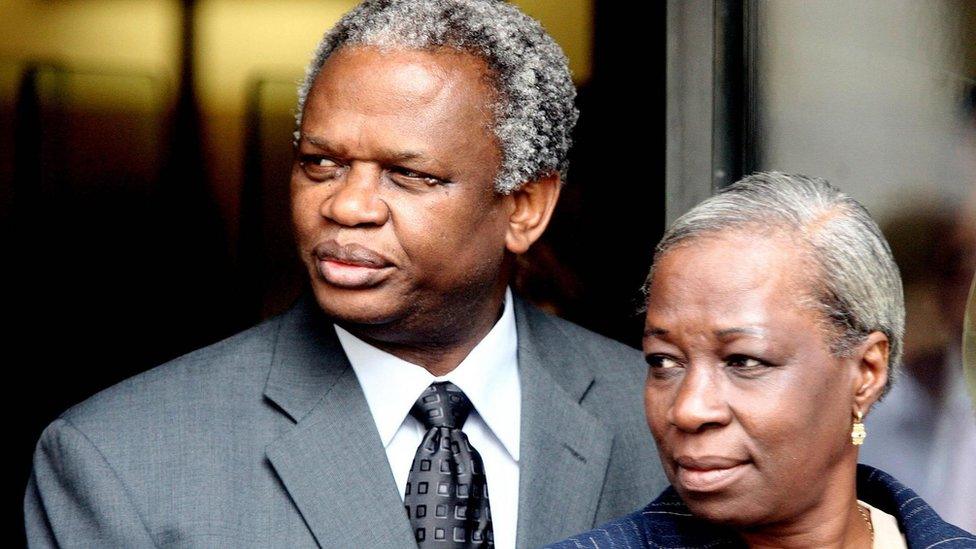

Damilola Taylor's father Richard says he still bears the pain of his son's killing

The Metropolitan Police knew its response to Damilola's death would be under intense scrutiny following criticism of its investigation into the killing of another black boy, Stephen Lawrence, in 1993.

While colleagues hunted Damilola's killers, Mr Jarman's role was to try to calm the fears of local residents and understand the wider context of a crime that shocked the UK.

Brought up by their single mother in Peckham, Danny and Rickie Preddie were members of the Young Peckham Boys street gang, which terrorised the North Peckham Estate at the time of Damilola's death.

It soon became clear local officers had underestimated the problems on the estate and had moved patrols away from the area.

"The community was very fearful of crime," Mr Jarman said. "Our analysis showed crime was not happening on the estate, but was happening in the shopping area, Queens Road and Rye Lane, and so we were more focused on those areas."

Mr Jarman said it made him wary of purely intelligence-led policing for the rest of his career.

Supt Rod Jarman, pictured with local MP Harriet Harman in the days after the killing, was tasked with trying to calm the fears of the community

Nick Ephgrave, now one of the Met's assistant commissioners, was a senior investigating officer in the re-examination of Damilola's murder in 2005.

He said breaking down a wall of silence within the local community was a real challenge for his team.

"We couldn't get enough information from the local community about who may be responsible. There was a real reluctance to speak out.

"There were lots of rumours and speculation but very little hard evidence.

"If we don't get information from people who live and work in the area, we're not really going to get anywhere."

This was something the Met has attempted to improve in recent years, Mr Ephgrave said.

The killing of the 10-year-old boy in south London shocked the UK

Damilola's death also led to improvements in police intelligence surrounding children in gangs, according to Mr Jarman.

"At the time of Damilola's death, there were a group of young people on the estate [who] had a hierarchy, which was a complete and utter surprise to us.

"If you looked at it now and compared it with an organised crime syndicate it would look very similar.

"We were also absolutely struck by the fact that there was a relationship between young people being the victims of crime and young people being offenders."

Damilola's mother Gloria Taylor, pictured with husband Richard at the time of the trial, died in 2008

However, youth worker the Reverend Denise Parnell was less surprised by this connection.

She had set up a youth club the year Damilola was killed, as she had become increasingly worried about the safety of local children.

There was a common misconception among them that stabbing someone in the leg would not kill them, she said.

When Damilola's death proved that wrong, Ms Parnell said she saw an escalation in violence as local teenagers became frightened and reckless.

Her daughter, Mikel Griffiths, was the same age as Damilola in 2000.

"It was frightening because for the first time the gang violence was not just between 14-year-olds and 15-year-olds, they were now coming for us," Ms Griffiths recalled.

"As the story unfolded about who Damilola really was, it was more frightening because we realised, hold on, he was just a normal kid, he was not getting into any trouble, he was a nice young person."

But 20 years on, Ms Parnell said she continued to have the same conversations with young people. "The street is still the street," she said.

"The problem has not got any better and it's disappointing that it's still there," Mr Ephgrave said.

"The sad thing is that it only ends in one of two ways - the grave or prison. And both of those options are tragic for everyone involved."

Britain's newspapers in April 2002 after the two brothers were initially cleared of Damilola's murder

Ms Griffiths has been determined to curb knife crime and has followed her mother into youth work.

She said she was still driven by the memory of what happened to Damilola.

"The image that always stays in my mind was his school picture that was on the news that night.

"It just showed innocence. An innocence that was taken, an innocence that was robbed for no reason.

"It's true that we have heard of so many killings since then, but there is something about Damilola's legacy that sticks with anybody who was around at the time.

"That face, you can't forget it, you'll never forget it."

- Published26 November 2010

- Published27 November 2010

- Published27 November 2010