'Life was a party before Aids arrived in London'

- Published

At the start of the 1980s, gay men in London started to be affected by a mysterious disease.

The first UK death from Aids was in the capital in 1981 - although it was only later this was confirmed to be down to an HIV-related illness. By the end of that same year, more than 100 homosexual men in the US had died as a result of the disease.

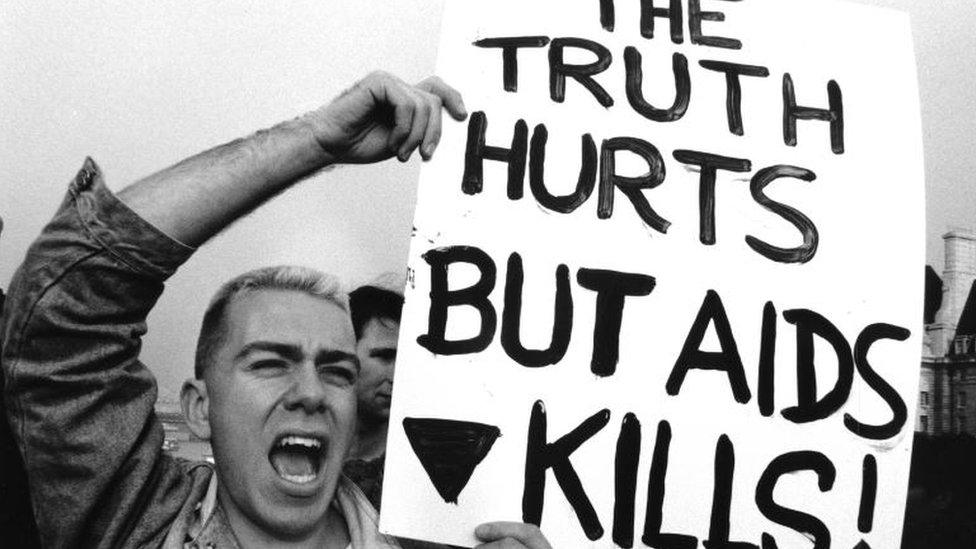

As time passed and the panic grew, gay people were ushered further into the shadows by a homophobic press campaign. Terms like the "gay plague" were widely used, and people believed HIV could be transmitted by any kind of proximity to those with the virus.

To mark the end of LGBT History Month, four people who witnessed first hand the struggles of those with Aids recall how what had been a vibrant gay community was devastated by the disease.

'He thought he could levitate'

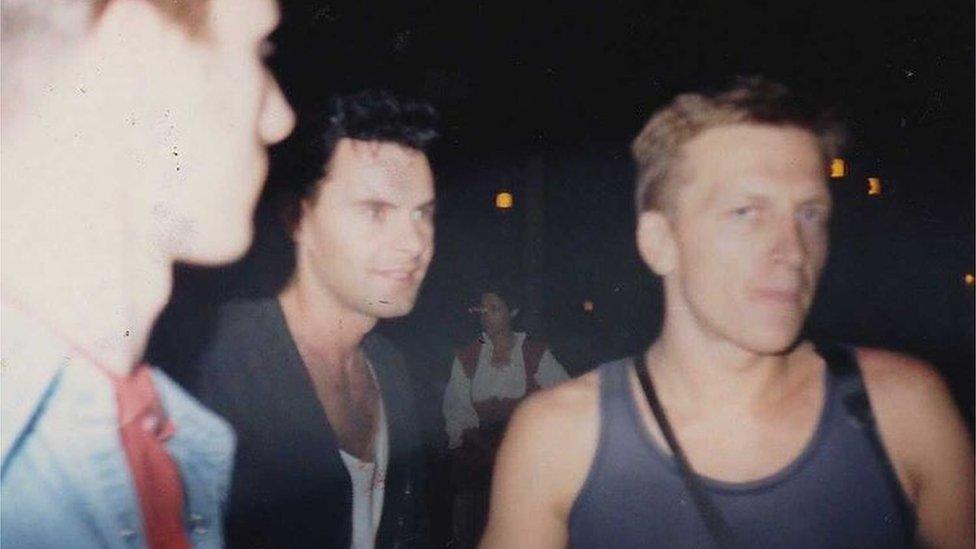

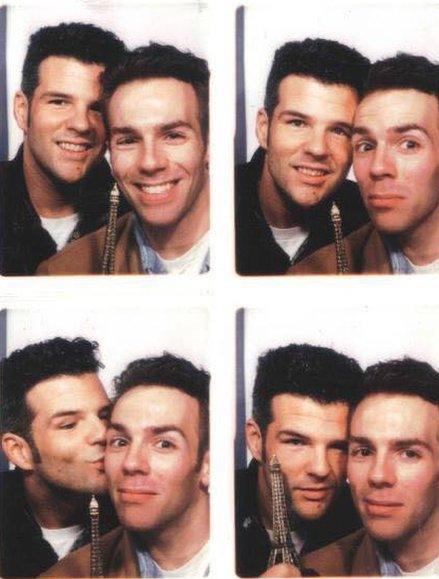

Julian Kalinowski (left) and his friend John Crancher (middle) were keen nightclub-goers in the 1980s

Julian Kalinowski was a young gay man in the 1980s and, like many, saw his social circle get smaller and smaller as the HIV and Aids crisis took hold. One of those who died was his close friend, John Crancher.

Born in Aberdeen, John - like many gay men - had moved to London in search of a better life. In the capital, he launched his fashion career.

"He progressed to having his collections shown at London Fashion Week and bought by high-end London stores," Julian said.

John Crancher moved to London in the 1970s

His career stalled, though, after he "began acting weirdly" at Camden Lock Market one day.

"Our friend Sandeep took him to hospital," Julian said. "Doctors told him he had full-blown Aids. I called his father in Scotland and asked him to come and see his son. He asked me why and I just said outright that John had Aids."

Julian said some of John's family refused to come to London, making him the primary visitor at his friend's bedside.

"I'll never forget John's terror in that tiny hospital room. He thought he had stigmata and could levitate," Julian said. "He had gone mad. I think it was the terror. Sandeep and I had to have him sectioned and we had to sign the documents. It was terribly harrowing."

John was only 28 when he died. Julian and his friends sold his old Vivienne Westwood clothes to help pay for the funeral.

John's death was the first of many, Julian said. "Those days were filled with hospital visits. We became very black-humoured about it, to cope. We used to say 'she's got bad knees, dear' - meaning 'she's knocking' [on heaven's door] and 'you'd better dust off that old black skirt again, dear'.

"It was shell-shock, really. A lot of people started using heroin around that time, to block it all out. On our scene there were as many overdoses as Aids deaths. The two correlated."

'It broke my heart to see him so sick'

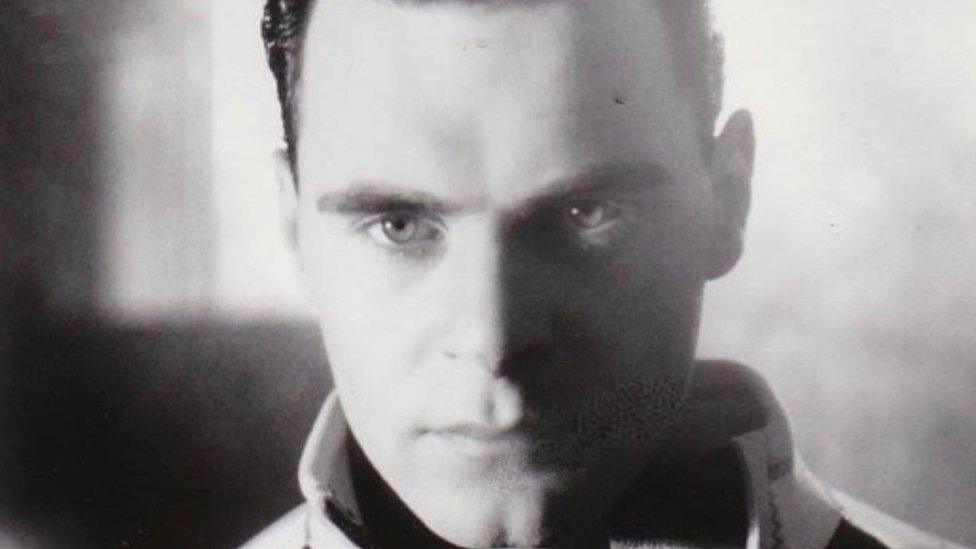

Ronnie Heyfron contracted HIV in his early 20s and died from Aids in 1990

Charli Hogan remembers whispers about Aids infecting men from the US and then in London, but it wasn't until her brother Ronnie Heyfron contracted HIV in his early 20s that she truly realised the severity of the disease.

For Ronnie, life was a party before Aids landed in London, his sister recalls.

He had featured in several pop videos, scoring a prominent role in Frankie Goes to Hollywood's hit Relax, Charli said.

"I remember being called at work in the summer of 1988. It was Ronnie. He said: 'Hi Sis darling, have you time for a chat?' 'Yes, of course boy, you sound worried,' I said back.

"I knew before he even said the words. My brother had tested HIV positive. He said: 'Don't worry sweetie, we fear the worst but hope for the best.'"

In the months that followed, Charli spent most of her days sitting at her brother's bedside at Westminster Hospital.

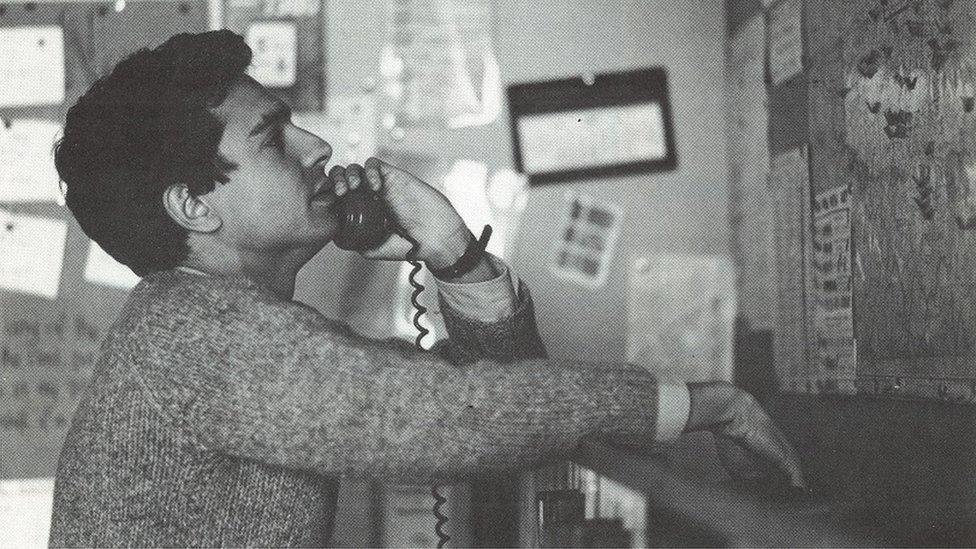

Mark O'Toole of Frankie Goes To Hollywood (right) on stage with Ronnie at Camden Palace in 1983

"I sat reading fashion magazines at his bedside, speaking about my tiny children whom he adored," she said. "We laughed, we cried. We reminisced about the showbiz parties where I stood back shyly, not having his sparkling wit and charm and outrageous sense of humour.

"It broke my heart seeing my handsome, strong brother losing weight and becoming so sick."

On his last day, Ronnie was weak and in pain, Charli recalls. He was 27. "At 15:40, his breaths got further and further apart. At 15:45, they stopped."

Ronnie died of Kaposi's sarcoma, a rare cancer caused by a virus that forms black or brown marks on the skin. It's often associated with HIV.

"Our beautiful boy: model, dancer, make-up artist supreme and best friend - we miss you every day."

'His lips were never that cold'

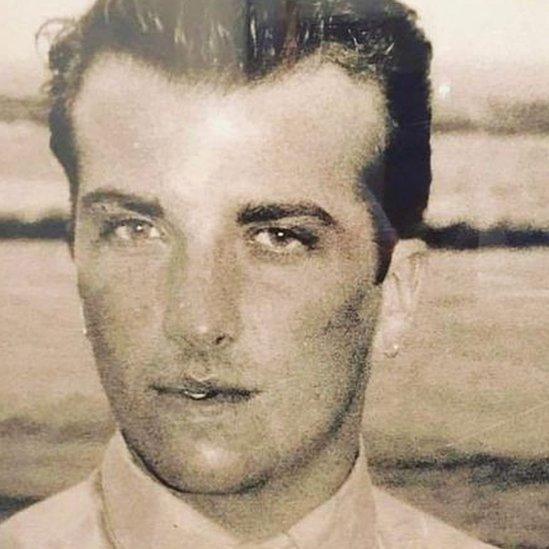

James Frederick (left) says he found about about Gino Calarese's HIV status on their first date

James Frederick's partner Gino Calarese discovered he was HIV positive in 1988 at the age of 20 while living in New York.

"He revealed his HIV status to me on our first date, assuming that it would be a deal-breaker because of the stigma and general lack of knowledge there was at that time," James said. "But it was too late. I had fallen head over heels for him."

Same-sex marriage was not legal in the US or UK at the time, so James and Gino held their own private commitment service and referred to themselves as "husband and husband".

At a time when knowledge about how HIV was transmitted was more limited, James said that despite the fact they always practised safe sex, Gino was terrified of infecting him.

"It was a certain death sentence, but I hoped advanced treatment could save my husband," James said. Gino only got sicker. He developed Kaposi's sarcoma and had bad side-effects from azidothymidine (AZT), an antiretroviral medication used by Aids patients at the time.

In 1992, the couple decided to move to London where Gino's parents were living and where he could receive better treatment on the NHS.

London's dedicated Aids ward at Middlesex Hospital was like being in an "alternate reality", James said.

"Even though Princess Diana had visited there a couple of years before, it still felt like there was such a disgrace about going to that ward. I spent two weeks there with Gino, nearly 24/7. There were screaming patients, medical emergencies, family fights and shunned partners."

Recalling the night Gino died, James said he watched as his husband became too weak to take medication.

"As I kissed him, I knew that he was gone," James said.

"Gino's lips were never that cold."

'These deaths were cruel'

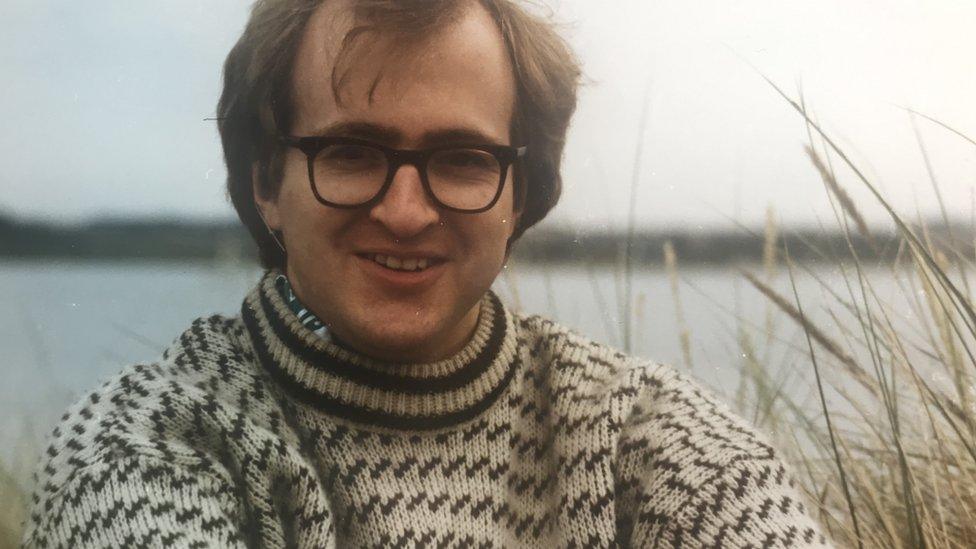

Peter Godfrey-Faussett was 28 when he began working on the Broderip Ward

Peter Godfrey-Faussett was a junior doctor on Middlesex Hospital's Broderip Ward, the UK's first ward dedicated to caring for HIV patients.

He recalls times of joy even amid the devastation.

"It was a bittersweet time of my life," he said. "The ward was full of a predominantly gay clientele who were at the front of London's vibrant 80s scene.

"There were lots of creatives - young men from the theatre, opera and fashion - all together on one ward. So we did have some fun.

"But of course the most devastating thing was the inevitability of their death. And it wasn't like any other death. These deaths were cruel."

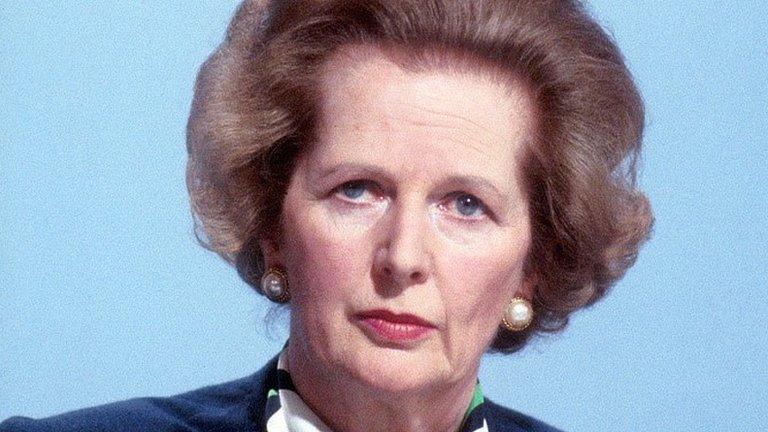

Diana, Princess of Wales, opened the Broderip Ward in 1987

Peter added: "Many of those needing care suffered severe weight loss and were often skeletal. Others had torrential diarrhoea, neurological problems or skin diseases, including Kaposi's sarcoma.

"For these body-conscious young men, some of the symptoms really took away their dignity. Our job was to simply make death better."

In the UK, about 106,000 people are currently living with HIV, with 98% of those on treatment.

Though having HIV is no longer a death sentence, Peter, who is now a UNAIDS science adviser, says the Aids epidemic is far from over. Globally, there were 690,000 deaths from Aids-related illnesses in 2019 and 1.7m new HIV infections.

"Ongoing stigma surrounding HIV still exists and prevents people from all communities, and particularity the African diaspora, from getting tested and accessing effective treatment or prevention promptly.

"We've come a long way, but there is still much more work to do."

Interviews sourced through The AIDS Memorial, external.

- Published19 February 2021

- Published11 March 2020

- Published5 April 2017

- Published23 November 2017

- Published8 February 2021

- Published4 March 2019

- Published18 January 2021

- Published5 February 2021

- Published5 February 2021