Aids campaign: Thatcher 'fought against risky sex warnings'

- Published

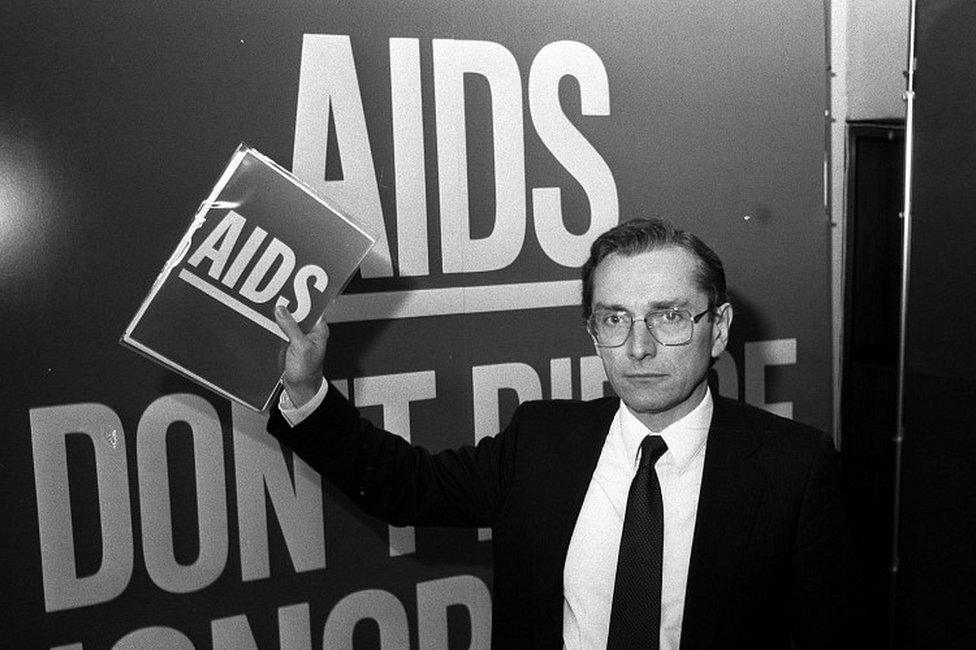

Lord Fowler said the 1986 Aids campaign contained "essential" information on personal behaviour

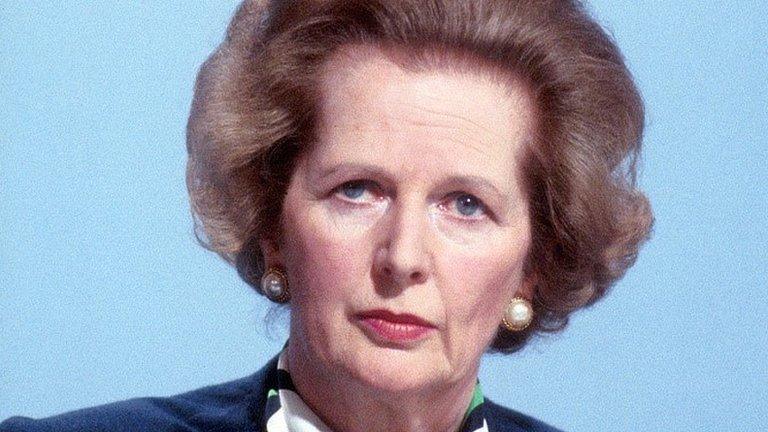

Margaret Thatcher opposed the use of warnings about "risky sex" in her government's Aids awareness campaign, her health secretary has said.

Lord Fowler said the then prime minister thought mentioning sexual practices in leaflets sent out in 1986 would make people "experiment".

"She was just wrong on that," he added, saying there was "absolutely no evidence that that took place".

More than 32 million people worldwide have died from Aids-related illnesses.

The first UK death was recorded in 1981.

The current Channel 4 drama It's a Sin portrays the sense of confusion and fear at the time. Rumours of a "mystery illness" affecting gay men in the United States abounded, but little information was available.

In 1986, the government, in which Lord - then Norman - Fowler served as health and social security secretary, launched its "Aids: Don't die of ignorance" campaign.

This included TV advertising and an information pamphlet, external stating: "Those most at risk now are men who have sex with other men."

"Right from the beginning Margaret was a sceptic about having this major campaign… on the dangers of contracting HIV and how you could avoid it," Lord Fowler said.

"There was a section in [the leaflet] on risky sex and Margaret came back on it and said, 'Do we really need to have this thing on risky sex?'

"Well, as the whole point of it was to warn people about it, it seemed to me that it was essential to have that in."

Margaret Thatcher had a "curious" attitude towards the campaign, according to Lord Fowler

Lord Fowler, who is currently Lord Speaker overseeing debates in the House of Lords, last year told the National HIV Story Trust, which is compiling an archive,, external that Mrs Thatcher had been "neurotic about getting too associated" with Aids.

But he told the BBC that, in hindsight, this had not been the "best choice of words".

He added: "Her concern was - it's always seemed to me a bit odd - that we were teaching people, telling people things about which they didn't know - the implication being that, once they knew it, then they would go out and experiment.

"Well, as this was exactly the opposite of our message, it did seem to me curious."

It was not until 1984 that scientists announced they had found a virus that caused Aids. Two years later this was officially named HIV (human immunodeficiency virus).

No treatment was available at the time of the government's campaign.

"There was nothing we could do for people who had contracted HIV," said Lord Fowler, "but we could warn those people who hadn't contracted it."

He and those who agreed with him "went round" Mrs Thatcher, using the cabinet committee on Aids, on which she did not sit, to set the official message, he added.

In the UK, as in the US, the government was accused of costing lives by acting too late in launching an awareness campaign.

"You could always say we should have started earlier," Lord Fowler said, "but I think we started at more or less the right time, because it was about the time when public concern was growing. We got it at that time and then we hammered it home."

Princess Diana was a notable campaigner on Aids awareness during the 1980s and 1990s

In February 1987, the World Health Organization launched its own Global Program on Aids to raise awareness. And a month later the first antiretroviral drug for treating HIV was approved for use in the US.

Until treatment became widely available, Lord Fowler said, the virus had effectively been a "death sentence".

He added that, in 1986, he had rejected calls for a "moral campaign" from some quarters, which would have focused on people changing their "sexual habits".

Lord Fowler, who is currently watching It's a Sin, called it "extraordinarily moving", adding that it shows the "helplessness" felt during the 1980s.

More than 100,000 people, external in the UK are estimated to be living with HIV today, the majority having acquired it through sexual transmission, rather than drug use.

The National Aids Trust charity says that the proportions of infections via homosexual and heterosexual intercourse are now "very similar".

If diagnosed early, treatment keeps the virus under control and stops complications that can ultimately lead to Aids, meaning life expectancy is similar to that for people without HIV.

But the scale of deaths globally. especially in countries where medical help is not available, concerns Lord Fowler.

"I don't think the sense of public outrage is as strong on that as I'd like to see," he said. "We've still a hell of a long way to go."