Covid: The London hospital staff who have spent a year on the front line

- Published

Lewisham Hospital: One year after ‘patient zero’

Since coronavirus reached the UK about a year ago, there have been more than 670,000 positive cases in London alone. On 9 February 2020, a patient who had just returned from China arrived at Lewisham Hospital in the back of a taxi. She was London's first documented Covid-19 case.

At first there was a trickle of Covid patients at the south-east London hospital, but within weeks staff were overwhelmed. Operating theatres and other areas were turned into temporary intensive care units.

At the peak of the first wave, staff were treating about 350 patients at the Lewisham and Greenwich NHS Trust, which runs Lewisham Hospital as well as the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Woolwich. At the height of the second wave, there were 500 positive Covid cases, and the trust came close to running out of room.

How are the medical professionals at the hospital faring after a year on the front line?

'I spend 20 minutes in my car before going home'

Itohan Ibude says colleagues being contacted by NHS Track and Trace is causing staffing issues

Itohan Ibude runs Lewisham's Chestnut Ward. The 39-year-old nurse is used to seeing a high turnover of patients, but the volume of coronavirus cases was like nothing she had ever witnessed.

"Patients with Covid generally have problems breathing," she says. "It's very distressing for staff to see people struggling for breath.

"It's hard for our staff to see a deteriorating patient admitted to ICU and we have regular debrief sessions to help us all cope."

On 9 February a woman returning from China arrived at Lewisham Hospital's A&E showing coronavirus symptoms

For Ms Ibude, from Bellingham in south-east London, there are many days she cannot forget.

"The first wave was patients with comorbidities," she says. "This second wave, we have had younger patients come in.

"We had a family of three admitted to this ward. Two of them recovered but sadly the dad passed away. That made it worse for me knowing how that story ended.

"I am a mum myself, I did think how it was going to be for [his wife]... there is guilt every day when I go home.

"The guilt will always be there. As a nurse, what we are used to, and see the majority of the times, is seeing that patient go through deterioration, through the phase of improvement and then discharged. But when you see people deteriorate, you feel you haven't done anything even though you have done everything.

"Sometimes when I leave here I sit in my car for 20 minutes. I think of my whole day, but I know that reflection is not going to change anything."

'Uganda was closing its borders so I returned'

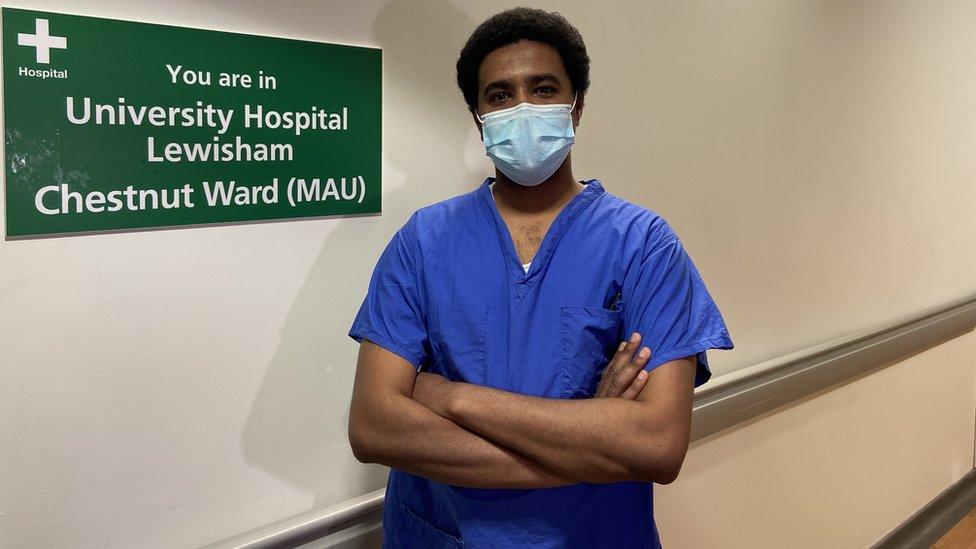

Since February, Dr Ed Scott has been working as a registrar in Lewisham Hospital's intensive care unit

At a time when Covid-19 was still a mystery virus in China, junior doctor Ed Scott was starting a new role in the Ugandan capital of Kampala.

The 29-year-old anaesthetist was taking some time out from treating patients at the Lewisham Hospital to help African children with cleft palates and other medical conditions.

But his plans changed.

"They were starting to shut down borders in Uganda," he says.

"It was either trying to leave and come back or potentially be stuck there for the foreseeable future. I knew it was difficult in Lewisham, I had friends and colleagues saying how busy they were.

"Everyone was stretched pretty thin; nurses working ridiculously hard, physiotherapists and other staff on the ward faced with more work than they were used to."

There are currently about 300 Covid patients who are at the trust's two hospitals

Nearly 1,000 patients are known to have died with Covid across the NHS trust.

Many of the patients who do die on the wards do so alone, as there is a strict no-visitor policy to stop further infections.

For Dr Scott this is the worst thing about the pandemic.

"We do our best to update family members to let them know what is going on with their loved ones," he says.

"If we have got 25 or so patients in critical care and you're one of four doctors on the ward then you're making up to six calls a day.

"Unfortunately, a lot of them are not happy calls... they are calls discussing patients not doing very well or bad news where patients have died.

"Making those conversations four, five, six times a day and can be really difficult.

"I think we are all trying to remain as positive as we can be. There is a light at the end of the tunnel so we are all clinging on to those positive thoughts."

'Steroid treatments can induce diabetes in Covid patients'

Dr Mohamed Bakhit says that a high proportion of Covid cases are among people with diabetes

NHS research revealed a third of coronavirus deaths between 1 March and 11 May were linked to people with diabetes.

It has meant specialist diabetes consultant Dr Mohamed Bakhit has had to monitor his patients even more closely.

"In the first wave we noticed that many people were coming in with coronavirus who were not known to have diabetes," Dr Bakhit says.

"They would come in with quite a bad diabetes presentation and would have high glucose levels, and their organs would just start shutting down, and we wondered what was going on.

"With time and more studies, we now know that if you have diabetes the likelihood that you get a bad coronavirus infection is higher.

"We also know that even if you don't have diabetes, contracting coronavirus can progress into having diabetes via various mechanisms including affecting how your pancreas produces insulin."

The mortality rate is much lower in the second wave of coronavirus, in part because doctors are armed with this kind of knowledge.

Lewisham Hospital is part of the Lewisham and Greenwich NHS Trust which has seen nearly 1,000 deaths linked to Covid-19

Steroids are more commonly prescribed than they were during the first wave, although as Dr Bakhit points out, this can cause problems.

"Steroids can sometimes induce diabetes. Also, some patients who are admitted with Covid have undiagnosed diabetes.

"Diabetes with Covid is difficult to manage and control, and I need to see patients on a daily basis.

"The workload has increased as follow-up is really important for diabetic patients, so the team has to make many calls each day to patients who have been discharged.

"A high proportion of Covid cases are amongst people with diabetes, although we still don't understand why this is.

"Numbers are coming down quite quickly, but we have to be cautious and anticipate what happens next. We look at things as they happen but hopefully we will get back to normal as more people get the vaccines."

'I am teaching Covid patients how to breathe again'

Harriet Bryce: "What we love is seeing a patient recover and progress"

Harriet Bryce works as a respiratory physiotherapist and would normally treat patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, external (COPD) or cystic fibrosis, but for the past year she has been focused on treating coronavirus patients.

"I wasn't at work the day the first patient came to Lewisham, but coming in on the Monday there was definitely a different sense in the air... of fear, the unknown, and what we would expect over the coming days and weeks."

Respiratory physiotherapy is a key part in the recovery of Covid patients.

Staff took part in the Clap for Carers initiative during the first wave of coronavirus

Ms Bryce says many patients come to Lewisham Hospital gasping for air.

"As they get better I start rehabilitation, which begins in critical care even when patients are sedated," she adds.

"I move their limbs while they are asleep, and position them to help with their joints and skin. As they wake up I get them to do simple bed exercises, and I then get them sitting up in bed, sitting in a chair, and eventually walking to build up their strength.

"Sometimes patients need further rehab once they are discharged to help them get back to doing daily tasks and get their lives back.

"What we love is seeing a patient recover and progress towards going home. It makes it all worthwhile.

"It is extremely rewarding when we see patients get better and hearing back from patients - a few have been in contact to let us know how they are getting on and it is those memories you really need to hold on to to keep going through this second wave.

"We have to stay positive and hope that the end is in sight."

For more London news follow on Facebook, external, on Twitter, external, on Instagram, external and subscribe to our YouTube, external channel.

Related topics

- Published27 October 2020

- Published8 January 2021

- Published13 January 2021

- Published18 January 2021

- Published22 January 2021