Grenfell Tower inquiry: Cladding firm 'knew of fire risk'

- Published

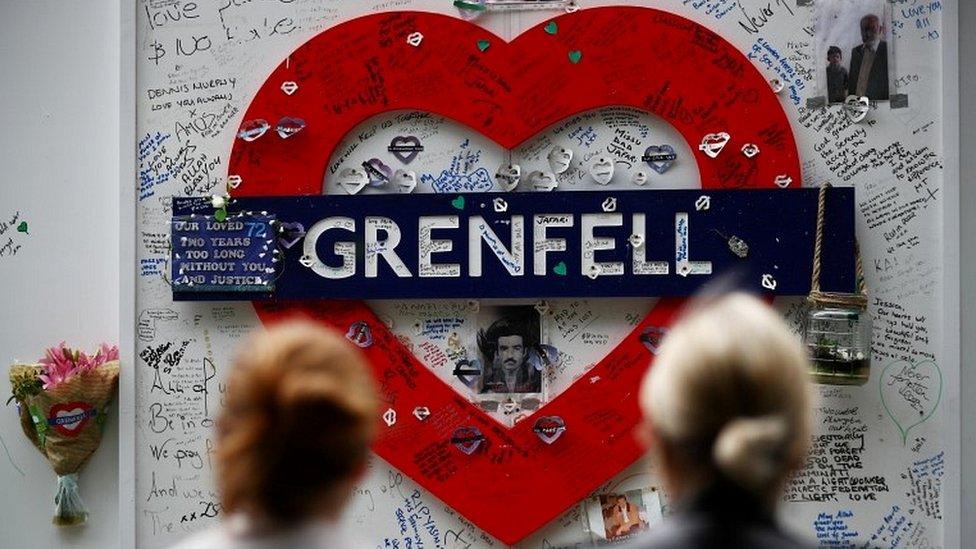

A fire destroyed Grenfell Tower in June 2017, with the loss of 72 lives

The firm that sold the cladding used at Grenfell Tower knew about the risk of fires in 2013, but continued to offer a flammable version of it.

The public inquiry has been shown an internal email sent by a sales manager at Arconic warning of the risk of high-rise fires in the United Arab Emirates.

Deborah French also forwarded an email from a competitor company that was switching to sell only fire-resistant cladding as a result.

Seventy-two people died at Grenfell.

On Wednesday the inquiry has focused on what Arconic told its customers, who were fabricating cladding systems for high-rise blocks around the UK.

On 1 May 2013, the BBC reported on "towering inferno" fears following a series of fires involving cladding in the Gulf.

Deborah French sent a link to the article and also forwarded an email from Richard Geater, a rival salesperson for another company, Alucobond, who was warning his customers of the risks.

Mr Geater wrote that using cladding known as aluminium composite material (ACM), made partly from plastic, created a situation like "a chimney which transports the fire from bottom to top or vice versa within the shortest time.

"The perils of using cheap ACM alternatives have been exposed," he said.

Arconic did not follow its competitor's lead. Its most popular type of cladding in the UK was Reynobond PE, with its flammable plastic layer, used on dozens of buildings including Grenfell Tower.

On 13 May 2013, Deborah French wrote to her customers saying that by working closely with them, "we are able to follow what type of project is being designed/developed and then offer the right... specification".

However, since the fire, Arconic has insisted it had no control over the type of materials it sold to customers, taking the position that it was for architects to decide whether they met fire safety regulations.

In a later witness statement, Ms French adopted this position, saying that in her email to customers she had simply meant the company's technical support department could offer advice if needed.

Richard Millett, the inquiry's lead counsel, questioned her about why, if the email was false, she had sent it in the first place.

He suggested the email might have been correct and that she had changed her account since the fire, despite being content to say at the time that Arconic could control the types of cladding used.

'Bad behaviour'

The degree to which Arconic "pushed" flammable cladding for use on tall buildings is central to the question of who might be to blame for the fire.

The timing of Ms French's emails is relevant. She was negotiating with the Grenfell Tower project for the sale of 3,000 sq m of cladding.

She admitted to the inquiry that at the time she knew this was a high-rise residential housing project.

By this point, Arconic had already changed its marketing materials after receiving poor fire test results for the Reynobond cladding sheets.

But a technical manager at Arconic said customers would only be informed "when asking about the fire performance" of the product.

The change was made a year earlier, in 2012, as designers were starting to consider materials for Grenfell Tower.

Despite "bad behaviour" in fires, the company believed the product could still be sold in countries with less restrictive regulations.

These included the UK where it was the standard type of cladding the company sold.

The UK sales manager involved in the discussions explained to the inquiry that she could not remember being told about the change to the specification, or it being discussed at meetings.

Arconic sold raw aluminium cladding sheets, which were formed into "cassettes" - rectangular folded panels - for fixing on the outside of buildings.

In 2010 Arconic published a specification for its cladding, which contained a fire classification of class B out of a possible A1 to F.

But in 2011 the "cassette" version of the product was put through a standard European fire test where it achieved a poor result, classified E out of a possible A1 to F.

The test went so badly it had to be stopped early, with the panel on fire.

As a result in 2012, the flammable version of the cladding was removed entirely from the specification sheet published by Arconic, despite the fact that it continued to be the main type sold in the UK.

Only a less common fire-retardant version was included in the information.

The BBC previously revealed that poor test results were withheld from the British Board of Agrément which issues independent safety certificates relied on by construction firms and architects.

A witness statement provided by a French technical manager, Claude Wehrle, said: "The intention was for customers to be informed of the position when asking about the fire performance of the cassette variant of the product."

However, Arconic continued to sell the product to construction projects involving tall buildings.

In a meeting note, Mr Wehrle wrote that "for the moment, even if we know the PE (polyethylene material) in cassette has a bad behaviour exposed to fire, we can still work with national regulations who are not as restrictive".

Arconic's UK sales manager, Deborah French, was asked by the inquiry's lead counsel: "Do we take it... that if the customers didn't ask, they didn't get told?"

"Yes," she answered, adding that they would not have known unless they had been told.

The cassette version of the cladding, formed from flammable materials, has been shown to pose a particular risk in fires on tall buildings and was the type eventually used at Grenfell Tower.

- Published9 February 2021

- Published8 February 2021

- Published19 January 2021